“I am a woman and I am poor.” Saying it out loud was harder than she had thought it would be. The words came out raw and harsh, like freshly hewn granite. “Two things entirely out of your experience.”

“What does that have to do with anything?”

He meant it, too. He really had no idea. Arabella looked at him, at the richly embroidered brocade of his waistcoat, the gold fobs jangling from his watch chain, the boots from Hoby, the coat from Weston, the large cameo embedded in the folds of his cravat.

The waistcoat alone probably cost something akin to her father’s annual income, an income expected to house, feed and clothe four people. Five, if Arabella found herself forced to leave Miss Climpson’s.

“I am an employee at your sister’s school. I don’t have the liberties you have. If we go on like this, I’ll only end by getting sacked.”

“I didn’t mean — ”

“It doesn’t matter what you mean or didn’t mean. And it wasn’t entirely your fault.” One didn’t blame a puppy for chasing after sticks. The fault was with the person throwing the sticks. “I should have known better.”

Turnip followed along after her. “I never wanted to make trouble for you. What can I do? How can I help you?”

Arabella moved sharply out of the way of his outstretched hand. “You can help me by staying away.”

Turnip stood rooted in front of the mantelpiece, staring at her with a puzzled little frown between his eyes. “You don’t really mean that. Do you?”

No, she wanted to say.

“I wouldn’t say it if I didn’t.”

Turnip looked as though she had slapped him. He stared at her, hurt, uncomprehending.

Arabella folded her arms protectively across her chest. “My life was perfectly rational until you came into it. There was no nonsense about puddings and spies. I didn’t go lurking around in the dark with strange men or... or...” She looked away. “Well, you know. The rest of it.”

He was still staring at her, as though seeing her for the first time. She didn’t want him to look at her like that. She had much preferred the way he had looked at her before. But that had been the very thing she had been complaining about, so how could she complain if he didn’t? She made no sense, even to herself.

“Beg pardon,” he said stiffly. “Swept away by circumstances and all that. Shouldn’t have forced myself on you.”

He hadn’t, and they both knew it. That just made it worse. He might have kissed her first, but she had been an enthusiastic participant in everything that had followed. And she knew, with humiliating certainty, that if he had made any sort of gesture, showed any inclination in that direction, she would have done so again.

Fortunate for her that he hadn’t.

“Under the circumstances,” said Arabella, in a voice she hardly recognized as her own, “I think it best our acquaintance be at an end.”

“If that is what you want.”

“It isn’t a question of want.” She sounded so priggish that it hurt to listen to herself. “It’s a question of conventions. And circumstances.”

“Can’t argue with circumstances, can one?” He smiled a lopsided smile without any humor in it.

It hurt to look at it.

Arabella’s mouth ached with the need to say something, to protest, to argue, to soften the blow, but she couldn’t seem to force any words past the large lump that seemed to have formed at the back of her throat.

Instead, she just nodded, a surprisingly tentative motion of her chin.

“I’ll leave first.” Mr. Fitzhugh — he was Mr. Fitzhugh now, she reminded herself, not Turnip anymore, never Turnip. Mr. Fitzhugh looked at her for a moment, all the light gone from his eyes. She had never seen him like that before. She hadn’t imagined he could look so... blank. So remote. “Wouldn’t want to cause you further bother.”

“I — ”

But it was too late. The click of his boots against the floor drowned out her feeble attempt at articulation. For a moment, he checked in the doorway, and Arabella thought he might say something else.

The door swung shut, and he was gone.

Arabella waited five minutes before following after him. Staggering their departures had been a surprisingly sensible suggestion on his part.

Why should she be surprised? Arabella leaned an elbow against the mantel, rubbing her face with her hand. So far, of the two of them, it was a toss-up as to who had shown the least sense. It was very easy, she thought, to criticize the actions of others, to upbraid them for folly, and very different when one found oneself in unpredictable circumstances, behaving in ways one would never have imagined of oneself.

Well, she had quite effectively put an end to all that.

The second hand on the mantel clock jerked stiffly up towards the center. One more minute and she could go. She tried to wipe away the image of Mr. Fitzhugh’s face, hurt and confused, his hand extended to her, palm up.

She would introduce Lavinia to Miss Climpson, she told herself brightly, pushing open the drawing-room door. This would be an excellent time to broach the topic of waiving Lavinia and Olivia’s school fees, while the headmistress was still flushed with Christmas feeling and lightly spiked punch. She would introduce Lavinia and laugh over the performance with Jane and forget that there was such a person as Turnip Fitzhugh in the world.

Arabella paused as she passed the door of the music room. Unlike the other doors on the hall, it was open.

She was about to turn, to close it, when someone jumped out from behind the door. She had only a confused impression of the edge of a white robe, like the innumerable white robes she had sewn for the shepherds and the angels and the wise men, before someone grabbed her from behind, hard enough to knock the air out of her.

Arabella staggered, gasping for breath. She tried to push away, but her assailant was too strong for her. Pinning her arms behind her back, he dragged her backwards into the dark of the music room, her heels skidding against the polished wood of the floor as she struggled for some sort of purchase.

Silver flashed in front of her as something narrow and hard was applied to her throat.

“Where is it?” a muffled voice rasped. “What did you do with it?”

Chapter 18

Turnip blundered down the hallway. He felt the way he had, some years ago, when he had taken a tumble out of his tree house and landed on his head. The fingers the doctor had held up in front of Turnip’s eyes had blurred and twisted just as the ranks of doorframes to either side of him were doing now.

What had he done?

One minute, she was clinging to his neck, the next she was acting as though he were a Mongol horde who had just personally ravished her village. All he had tried to do was express a concern for her safety, and what had she done? Ripped at him like a whole flock full of harpies.

Why was it suddenly best that their acquaintance be at an end? And all that about her reputation and being a woman and poor and his just not understanding. She was right about one thing: He didn’t understand.

Well, fine. He might take a while to get the message, but let no one say that he didn’t get it eventually. If she wanted him gone, he would go. If she had any intruders that needed dealing with, she could jolly well deal with them herself.

Not that he wouldn’t help her if she came running to him. Turnip contemplated the highly pleasing image of Arabella, in disarray, her hair all down around her back, flinging her arms around his neck, murmuring that she had been wrong, all wrong, and needed him desperately.

Needed him desperately? The image disappeared with a pop. Arabella was about as likely to say that as he was... well, as he was to take tea with Bonaparte. And her voice had come out at least an octave too high. She would more likely say something sarcastic and try to deal with it all herself.

“Mr. Fitzhugh,” someone said warmly, and Turnip made a manly effort not to jump out of his own skin.

“How nice to see you again,” said the woman who had come with them to Farley Castle.

Miss Anselm? No. Arden? Not that either.

“Nice to see you again too, Miss, er...”

Arabella’s friend tilted her head up at him. She afforded him a long, speculative glance that made Turnip feel a bit like a butterfly on a botanist’s table. Turnip tugged at his cravat. “Austen. Miss Dempsey and I were neighbors in our youth.”

Turnip felt like the worst kind of a heel. He had only spent several hours in an open carriage with her, after all. “Didn’t mean — that is to say — ”

“It’s quite all right,” said Miss Austen. She smiled up at him, her eyes bright with amusement. “I had the advantage of you and used it shamelessly. You appeared to be in a bit of a brown study.”

Or just the study, the one down the hall. “Oh, no, nothing like that,” said Turnip too jovially. “Just musing about the Nativity. Bethlehem. All that sort of thing.”

Miss Austen raised her brows, but forbore to comment. “Will you be celebrating the Christmas season in Bath, Mr. Fitzhugh?”

“Me? No. Just here to fetch m’sister, Sally, and then I’m off to Girdings House.”

“Girdings House?” Miss Austen seemed rather struck by the news. Turnip supposed it made sense, one of the great houses of England, and all that.

“Yes, in Norfolk.”

Miss Austen regarded him thoughtfully, but all she said was “That is the principal seat of the Duke of Dovedale, is it not?”

“Never actually met Dovedale — he’s been away for dogs’ years — but the Dowager Duchess of Dovedale is hosting a big thingummy.”

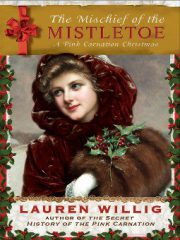

"The Mischief of the Mistletoe" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Mischief of the Mistletoe". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Mischief of the Mistletoe" друзьям в соцсетях.