Now that was a brilliant plan. Maybe she should suggest it.

“. . . could use vocabulary charts as the decoding key. Don’t you see? Then...”

Arabella could see Turnip’s lips moving and his hands rising and falling as he gesticulated, but the words themselves were entirely drowned out by the angry roaring in her ears.

“There are no spies.”

Turnip took a step back under the force of her statement. “Pardon?”

“Read my lips.” Turnip obediently looked at her lips. Arabella enunciated very carefully. “There are no spies. There are a series of schoolgirl pranks and a mildly mad music master with poor taste in facial hair. But there are NO SPIES.”

Turnip rubbed his ear. “Didn’t need to read your lips for that. They could hear you in France.”

“Good,” said Arabella viciously. “I am sick unto death of spies. Your sister and her friends are all spy mad. I don’t know why they can’t swoon over Drury Lane actors like normal sixteen-year-olds.”

Turnip looked at her with interest. “Did you swoon over Drury Lane actors?”

Kemble had been lovely in his tights. She had kissed her copy of A Midsummer Night’s Dream before going to bed every night for an entire month.

There were some truly gemlike lines in that particular play. But there was one line above all that stood out as particularly apt to the occasion: Lord, what fools these mortals be.

Of the two of them, she wasn’t sure who was the greater fool, she or Turnip. It was a close-run contest.

“That,” said Arabella stiffly, “is beside the point.”

“I can understand,” Turnip said, very carefully, the way one might to a peppery maiden aunt or a child prone to tantrums, “how this can all be a bit unnerving if you’re not accustomed to the idea...”

“I see no need to grow accustomed to the idea,” Arabella said through gritted teeth.

“Felt that way myself until I met my first French spy,” expounded Turnip avuncularly. “Deuced unsettling experience, that.”

“What did he do?” asked Arabella acidly. “Ask you to conjugate irregular verbs?”

“She, actually,” said Turnip mildly. “And she pointed a gun at me. Thought I was the Pink Carnation.”

“Oh.” That took the wind out of her sails.

Turnip followed up his advantage. “Someone might have hurt you, tearing up your room like that. Sally said the mattress was slashed. What if you’d been there at the time?”

“Then I imagine they would have gone away again.”

“What if they had come at night?” Folding his arms across his chest, he leaned against the window frame, looking intently at Arabella. “What if you were sleeping?”

It was a more unsettling image than she cared to admit. She could picture her room, entirely dark except for the faint illumination of the moon. She had always been a heavy sleeper. The room wasn’t large. It would take only a moment for someone to climb from the desk to the bed. And once there...

Arabella shrugged. “I doubt they would have bothered. Not everyone has your penchant for trellis-climbing.”

Turnip slowly uncrossed his arms. Straightening from his recumbent position against the window frame, his eyes locked with Arabella’s. “That depends on what’s at the top of the trellis.”

Arabella could feel color flare in her cheeks. For a very long while, they just looked at one another, and she knew he was remembering, as she was, exactly what had happened at the top of the trellis the other night.

Arabella looked away first. She licked her lips, which felt uncomfortably dry. “This is a ridiculous discussion. There is no point to it. Even if there were dangerous spies who for some obscure reason wanted a commonplace notebook full of French exercises, they have what they came for. There’s no need for them to bother me again. I’m perfectly happy to leave them alone if they leave me alone.”

“What if they don’t? What if they think you know something?”

“What? The recipe for the perfect pudding?” Arabella sat down heavily on a blue silk upholstered chair.

It would be easier to stay annoyed with him if he didn’t seem so genuinely concerned for her safety. Even if he was being absurd. She felt, suddenly, very tired. She had been on edge all day, the knowledge that she would see Turnip fizzing through her veins, distracting her from her work, making her hands tremble as she pinned hems and put up scenery. She had spent hours rehearsing and revising hypothetical conversations. In some of them, he had been apologetic and she had been gracious; in others, he had been noble and she had been humble. All of her imaginary conversations had one thing in common: In none of them had anyone said anything about spies.

She knew it was foolish, but Arabella felt distinctly let down. So much for her brief career as a romantic heroine. She had been upstaged by a notebook full of amateur French exercises.

Two worried lines indented the skin between Turnip’s brows, and there were lines on either side of his lips that had no place on his goodhumored face. He leaned over her, planting a hand on either arm of the chair, his fingers digging into the pale blue silk upholstery, and Arabella tried not to think of how those fingers had felt in her hair two nights before, or how much like an embrace it seemed.

His mind, at least, was not on dalliance. “It isn’t funny,” he said, leaning so far forward that she could smell the cloves on his breath and see the tiny gold hairs in his skin. “You could be in danger.”

Arabella looked down and away, staring at the gray fabric of her skirt. There were lines in the twill if one looked closely enough. It was an ugly fabric, heavy and serviceable. Not the sort of thing a Turnip Fitzhugh would ever encounter, but highly appropriate for what she was: a schoolmistress.

“The only thing I am in danger of is losing my position.”

As she said it, she knew it was true. Miss Climpson might be an indulgent, one might even say an absentminded, employer, but she could not possibly condone her instructresses cavorting in darkened rooms with the older brothers of students. It set a bad tone, especially in an institution where one of the students had already been caught in similar behavior. A schoolmistress at an academy for young ladies had to be like Caesar’s wife, above reproach.

Arabella might, just might, manage to pass their current tête-à-tête off as a consultation between a teacher and a concerned brother — it was a drawing room, after all, and there were candles lit — but their interlude in her bedroom the other night was completely indefensible, by any standard. She ought to have sent him packing the moment she saw him sitting there on her desk. No, more than that. She should have slammed the window when she saw him lurking outside the drawing room.

But she hadn’t. She hadn’t because she had wanted to see him, because she had been happy to see him, because she had been prepared to ignore all the potential ramifications in exchange for the immediate pleasure of his company, for that ridiculous, face-splitting grin and the absurd and unpredictable things he said and the way he looked at her, really looked at her, not as an adjunct or an addendum or another girl against the ballroom wall, but as if he saw her, Arabella.

And for that, she had been willing to play blind and deaf and dumb to potential disgrace and the failure of all her plans.

Lord, what fools these mortals be.

Arabella shoved her chair abruptly back, retreating towards the fireplace. “This is folly,” she said to the mirror over the mantel. “We can’t go on doing this.”

Turnip followed along behind her. “Doing what?”

He was so close that their noses nearly collided when she turned. Arabella took a few prudent steps back. “Meeting. Together. Alone. People will start to talk.”

Turnip’s face cleared. “Is that all?”

“All?” It seemed like rather a lot to her.

He looked at her earnestly, his blue eyes searching her face. “I don’t mind if they do talk. Do you?”

Arabella frowned at him. Didn’t he realize what that meant? That if they were caught together, there would be expectations, consequences?

Then realization hit. No one would expect him to make good for a schoolteacher, a woman of no money and undistinguished family. A woman whose aunt had titillated the ton by running off with a man half her age. Bad blood, they would all say. She would be used goods.

And Turnip could go back to kissing Penelope Deveraux on balconies off ballrooms.

“Yes!” Arabella’s fingernails cut into her palms. “I do mind.”

Turnip blinked at her. He looked... hurt? “Oh.”

Arabella pushed away from the mantelpiece, her ugly skirts heavy against her legs. She thought of Margaret and the little sisters she had left. She thought of Aunt Osborne and all the years of being quiet and good. “It’s all right for you to play at spy-catching,” she said, all in a rush. “It doesn’t matter where you go or who you’re seen with. You’ll always have a home to go back to. You don’t have to worry about what people think or getting your own living. I don’t have that luxury.”

“Arabella?”

She nearly weakened at the sound of her name on his lips. Whatever else one said about Turnip Fitzhugh, he had a beautiful voice, rich and deep. It turned her name into a thing of beauty, a jewel in a velvet case. He followed her, looking so confused that it made Arabella’s chest ache. She didn’t like herself very much right then. But she knew she was right.

“I don’t understand.”

Arabella gave a wild laugh. “I didn’t expect you would.”

Turnip looked at her expectantly.

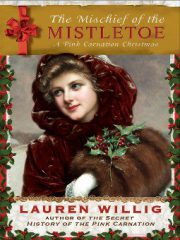

"The Mischief of the Mistletoe" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Mischief of the Mistletoe". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Mischief of the Mistletoe" друзьям в соцсетях.