Go generally meant go, unless this was one of those occasions where they — and by they, he meant the other half of the human race — were purported to say one thing but mean another.

“Are you upset because I climbed out the window? Thought you wanted me out the window. That’s generally what please go now tends to mean. Well, not the window, but the going bit. Could have taken the stairs, if that would have made you happier, but the trellis was right there.”

“Shhhhh!” Arabella hissed furiously. She cast an anxious glance at the camel. “Not in front of the livestock.”

She wiggled her way back into the booth.

Turnip wiggled in after her.

“Why won’t you talk to me?”

“I am talking to you. See? My lips are moving. Talking, talking, talking.” She shuffled the script, dropping half the pages in the process.

“I’ll get those!” Turnip dove for the ground, nearly upsetting the screen, which rocked on its base.

“No. Don’t. I’ll — ” Arabella drew in her breath with a hissing sound that Turnip didn’t need to be told meant she wasn’t precisely happy.

“Here you go.” He propped himself up on one knee and offered the pages up to her again. “Not all quite in order, but all here.”

There was a tap-tap-tap on top of the frame and the Angel of the Lord shone round about them. “Excuse me. In case you hadn’t noticed, we’re starting.” Sally looked pointedly at Turnip, who was still down on one knee. “That is, if you’re quite done with whatever it is you’re doing down there?”

“Righty-ho,” Turnip struggled up to his feet, trying not to topple over onto the screen. “Good luck. Break a leg — er, wing.”

The Angel of the Lord gave him a look and disappeared again over the partition.

Turnip turned back to Arabella, who was very studiously paging through the script, her cheeks bright red beneath the tightly coiled loops of her hair.

“Didn’t mean to upset you,” he whispered. “Last thing I wanted to do.”

“There’s no need to discuss it,” said Arabella in a low voice. She raised her voice, looking around. “Caesar? Has anyone seen Caesar Augustus? She’s meant to be on.”

There were the usual rustling sounds and hastily hushed whispers as the audience settled themselves in their seats. Miss Climpson mounted the makeshift steps to the stage, her spectacles reflecting the light of the candles so that they looked like carriage lamps. There were muffled giggles from backstage. Arabella held a finger to her lips and the giggles stopped.

“Friends, parents, neighbors,” declaimed Miss Climpson, opening her arms wide.

“And Romans,” muttered Turnip, pointing at Caesar Augustus. “Can’t forget the Romans.”

Arabella’s head remained studiously bent over the script. Ha. Turnip wasn’t fooled by that. He doubted Miss Climpson’s welcome speech had been included in the playbook.

The headmistress clasped her hands together and beamed myopically out over the assemblage. “We thank you for joining us here today. We know some of you have traveled long distances — ”

The headmistress babbled on. Turnip let the familiar words wash over him — she gave the same speech every Christmas; half the people in the room could have delivered it on her behalf without missing a single preposition — and directed his attention instead to Arabella, who was very studiously doing her best to pay no attention to him.

Turnip peered over her shoulder. The first part of the program was a dramatic reenactment of the Gospel according to Saint Luke, chapter two, verses one through fourteen, with additional dialogue by the staff of Miss Climpson’s seminary.

Turnip tapped a finger against the page. The fact that he had to reach over her shoulder to do it was a bonus. His sleeve brushed the fabric of her dress, making her give a little jump.

“Think I’ve read that before,” Turnip said. “Deuced good page-turner. Shepherds, wise men, mad emperors...”

“Augustus wasn’t mad.” Arabella was back to not looking at him. She addressed herself to the script in a monotone. “That was his — ”

“Wife’s great-grandson,” Turnip provided. “Caligula. Means ‘little boots.’ He was the son of Augustus’s wife Livia’s grandson Germanicus. Livia was the one with the poisoned figs, don’t you know. Shouldn’t have wanted to dine at her house.”

Well, that had got Arabella’s attention. In a why-is-this-madman-babbling-at-me sort of way, but at least she was looking at him. Turnip wasn’t picky. He’d take attention however he could get it.

“Nasty little nipper. Chip off the old family block. Caligula, I mean, not Germanicus. Wouldn’t believe some of what he got up to.” Turnip shook his head at the depravity of the Caesars. “Makes for good reading, though. Nothing like the odd orgy to get a chap learning Latin.”

Arabella cast a quick, alarmed look at the rear end of the camel, which was listening with a little too much attention. “I don’t think this is the time for orgies. Are you sure you wouldn’t like to find a seat? Miss Climpson is just — ”

There was a smattering of polite applause from the audience.

“ — about to be done.”

“If I sit down, will you talk to me after?”

Arabella frowned and held up one hand to signal him to wait. “Romans?” she called. “Romans? Onstage!”

The Roman Senate, consisting of five ten-year-old girls in togas, scrambled onto the stage.

“That’s a no, isn’t it?” whispered Turnip.

Caesar Augustus strutted onstage, laurel leaves tacked on with hairpins. “All the world shall be taxed!” she piped.

There was wild clapping from the audience, presumably from Caesar Augustus’s parents. No one got that excited about taxes. Except, perhaps, Mr. Pitt, who had once tried to talk finance to Turnip during Turnip’s short-lived career as Member of Parliament for Dunny-on-the-Wold.

Turnip made a mental note never again to pass out drunk in a rotten borough on the eve of an election, especially when the only other inhabitant of said borough was a dachshund named Colin. Next thing you knew, you were a Member of Parliament and Mr. Pitt was trying to talk finance to you. It hadn’t been all bad. He had gotten some jolly good naps on the back benches. Nothing soothed one to sleep quite like twelve hours of unbroken oratory. Nice benches, too. Soft. Padded.

Rather like Arabella.

He wasn’t supposed to be thinking about Arabella’s padding. Curves were also right out, despite the fact that the booth was very narrow and those curves were very much there, right next to him, pressed up against his side. He could feel her breast brush across his arm every time she reached out to turn a page.

The Romans might have known a few things about torture, but even Caligula at his most depraved could never have come up with this. He was watching a Nativity play, for the love of God. Turnip wasn’t quite sure, but salacious imaginings during the virgin birth did seem the sort of thing to send a chap straight to brimstone.

Onstage, a very bashful Mary, who couldn’t be more than twelve, was being tugged forward on a wooden donkey with wheels. Turnip did his best to stay quiet and quell lustful thoughts, but it was difficult with Arabella pressed up beside him, all warm and round and lilac-scented.

Turnip shifted uncomfortably. This was not helping. He took a deep breath and tried to concentrate on Joseph, who was currently haggling over the nightly rate of a manger. He had always felt more than a bit sorry for Joseph. Must be tough on a chap to get leg-shackled, only to find that your wife was expecting the child of God. Not that it wasn’t an honor and all that, but it did rather cut down on the canoodling.

Turnip was very relieved when the manger was wheeled out and the shepherds came on. One couldn’t whisper through the virgin birth, but shepherds abiding in the fields were fair game.

“And, lo,” proclaimed the narrator, shouting to be heard over the sheep, “the glory of the Lord shone round about them. And they were sore afraid.”

The farthest shepherd to the left gave her sheep a sharp crack with her crook as Sally appeared in all her feathery glory.

Ascending a very short ladder, Sally spread her wings and preened. The shepherds cowered before her.

Turnip regarded his sister fondly as she fluffed her feathers and graciously acknowledged the groveling shepherd people. Sally had a bit of Dowager Duchess of Dovedale in her. Not literally — as far as Turnip knew, the families weren’t related — but in spirit.

Turnip made sure to clap loudly, as promised, before turning back to Arabella. “Won’t you tell me what the matter is?” he whispered in her ear. “Why are you avoiding me?”

“Fear not! For behold — ”

Arabella jerked her head away. “I’m not avoiding you. I am trying to prompt a performance.”

“BEHOLD, I bring you — ”

“Then why did you keep running off earlier?”

“For heaven’s sake!” hissed the Angel of the Lord, appearing suddenly over the edge of the partition. “Can’t you see I’m being angelic?”

“Wouldn’t want to miss that,” muttered Turnip.

He turned just in time to see Arabella smothering a grin.

“For behold... ,” prompted Arabella, nodding to Sally.

Sally tossed her head. Taking leave of its pins, her halo soared out across the audience, like a discus at the Olympian Games. Children shrieked. Matrons ducked.

Arabella buried her head in her hands.

In the finest traditions of the theatre, Sally drew herself up on her stepladder, ignored the wires sticking straight out of her head, and carried grandly on. “For behold, I bring you good tidings of great joy...”

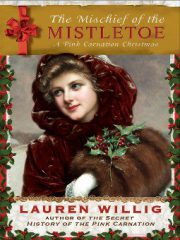

"The Mischief of the Mistletoe" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Mischief of the Mistletoe". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Mischief of the Mistletoe" друзьям в соцсетях.