“That was the chair,” she announced, after a period of brief but concerted observation.

Turnip gave up trying to kiss her and smoothed her hair back behind her ears. He followed the curve of her neck down to her shoulders, giving them a comforting rub. “I’m sure it’s all right. It’s a chair.” Chairs tended, in his experience, to be fairly resilient objects.

Arabella looked at the fallen chair and then back at him.

Then at the fallen chair. And then back at him.

Turnip couldn’t make out her expression — those poets who raved about starlight highly overrated its powers as a lighting agent — but he had the distinct impression that she wasn’t happy.

“At least it wasn’t the inkwell,” said Turnip cheerfully, in an attempt to lighten the mood. “That would have been a bother to clean up.”

Even without the inkwell, they had made rather a mess, Turnip had to admit. Not quite as bad as the drawing room — no broken cupids scattering porcelain all over the place — but her desk chair lay on its back, legs pointing stiffly out, and a notebook had fallen next to it, belching out paper as it landed.

“Arabella?” Turnip gave her waist a friendly squeeze. When that didn’t work, he tried again. “Miss Dempsey?”

Arabella twisted away from him. Her skirt swished against the uneven boards of the floor. “Mademoiselle de Fayette — she lives just downstairs,” she said distractedly. And then, when Turnip still didn’t get it, “You have to go.”

“What?” Turnip’s mind was still occupied elsewhere. Turnip reached for Arabella, asking, with his most winning smile, “What was that you were saying?”

Arabella gave him a little shove. “Please. Go. Now.”

“Oh. Right.” No mistaking the meaning of that. Clear as a bell. By no stretch of the imagination could it be translated as “Take me now.”

Arabella made shooing gestures.

Turnip scrambled up on the desk, sending bits of paper scooting left and right. The window was still open, and the trellis appeared to be where he had left it.

He looked back over his shoulder at Arabella, who was twisting her hands together and craning her head towards the door as though she expected a band of outraged Roman matrons to burst in at any moment.

It didn’t seem right to leave it this way.

Turnip paused with one foot out the window. “Just wanted to say — ”

Arabella jiggled up and down. “Go! Please.”

So much for tender expressions of regard.

“Well, good night, then.” Turnip lowered himself the rest of the way out the window, feeling for footholds in the façade. That had felt very inadequate, so he added, “Mind the mustachios!”

That didn’t strike quite the right note either, but he was now entirely out the window, clinging to the façade of the building, four stories up. Not exactly the best time for crafting the perfect parting phrase. If he had his friend Richard’s je ne sais whatsis or his friend Geoffrey’s brains, he might be able to pull it off, but he had enough trouble stringing the old words together when his feet were flat on the ground, much less when his extremities — and the rest of him — were dangling several flights up above hard flagstones and some deuced prickly looking shrubbery. And at that, the shrubbery was still preferable to the flagstones.

Turnip lowered himself hand over hand, concentrating on keeping his hands and feet away from the odd icy patch, wishing he’d remembered to put his gloves back on.

Three stories left to go now. The windows were all dark, which he supposed was a good thing, even if it did make feeling for handholds a bit dicier. It would be hard to explain what he was doing clinging to the side of the building in the wee hours. He supposed he ought to have thought of that before deciding to take the trellis. Next time, he was using the stairs.

Next time. A bit of vine stuck itself to his ear, tickling his nose. He hadn’t really thought about whether or not there would be a next time. Please go now was seldom conducive to next times. On the other hand, please go now wasn’t quite the same as never darken my trellis again.

He’d talk to her tomorrow, he decided. And they could sort it all out then. Among other things, there was still that last pudding to discuss. And whatever it was that Signor Marconi had really been doing, stalking the halls of the school by night. That was, Turnip remembered, with a certain amount of surprise, why he had climbed the trellis in the first place.

There was a rustling noise above him and he looked up to see Arabella leaning out the window. He had never noticed before what a nice chin she had. It was, at this angle, all of her he could see. That and her long hair falling out the window on either side of her face, like that storybook princess who used to let down her hair as a ladder.

“Be careful,” she called after him.

Turnip raised a hand in salutation before remembering that waving while clinging to the side of a building thirty feet off the ground was probably a very bad thing to do. He concentrated on climbing.

Upstairs, Arabella watched until she was sure Mr. Fitzhugh had safely reached the ground. He staggered a bit on hitting the pavement, then recovered and directed a jaunty salute in the general direction of her window.

Arabella yanked the window shut and latched it. Not that she thought anyone else was going to climb her trellis, but it never hurt to make sure. An ounce of prevention was worth a pound of cure. Arabella contemplated the wasteland of crumpled and ripped papers on her desk, one of which bore the distinct imprint of Mr. Fitzhugh’s shoe, and set about mechanically smoothing them flat.

She felt cold without Mr. Fitzhugh’s arms around her.

“That’s what shawls are for,” she muttered, slapping papers into a pile without bothering to make sure they belonged to the same composition.

Shawls couldn’t compromise you. Shawls couldn’t cause you to lose your position. Shawls wouldn’t regret kissing you in the morning.

There had been many grand moments of stupidity in the course of human history — Clarissa’s history composition numbered prominently among them — but surely what had just happened in this room had to take pride of place. Arabella yanked her fallen desk chair back into position, plunked the notebook back on the newly cleared desk, and counted the ways. She had (a) kissed Turnip Fitzhugh (b) in her bedroom (c) in his sister’s school (d) where she was an instructress.

Burying her head in her hands, Arabella added an extra item. (e) She had enjoyed it.

Somehow, that was worst of all. She wasn’t supposed to kiss Turnip Fitzhugh. And she certainly wasn’t supposed to like it.

Or want, so very badly, to do it again.

Since trellises were of limited utility during daytime hours, Turnip was forced to resort to a more subtle stratagem in his attempt to see Arabella the next afternoon.

Turnip drummed his fingers against his palm as he waited in Miss Climpson’s drawing room, now miraculously restored to a semblance of its usual state. Minus, of course, one china cupid.

One didn’t just go calling on schoolmistresses, at least not without arousing talk. Given Miss Dempsey’s reaction last night, Turnip had got the feeling — just a hunch, mind you — that she might object to that sort of thing. On the other hand, there was nothing to comment upon in a chap wanting to see his favorite sister.

Turnip basked in a combination of sunshine and smugness. The plan was so cunning, one could cut it with a weasel.

Turnip hopped to his feet as soon as Sally entered the room.

“Have you seen Miss Dempsey?” he demanded.

“What? No hello? No how are you?” Turnip’s sister seemed less than thrilled to see him. Sally folded her arms across her chest, her matched gold bracelets knocking against each other with a discordant clang. “You come barging in here in the middle of the day without so much as a note, drag me out of French class in the middle of the passé simple, and then ask to see my teacher?”

“Not as though you were paying attention in class anyway,” said Turnip sagely. “Now, where’s that teacher of yours?”

“Yes, but I might have done,” said Sally, “and now I’ll never have the chance. Then, after all that, it’s not even me you want to see. Not a bonbon, not a gift, not a single token for your one and only sister. No. I’m just a means to an end to you, aren’t I?”

“That was the idea,” said Turnip, ignoring the long windup. He knew this prelude. All it meant was that Sally had her eye on something and wanted him to pay for it.

Sally clasped her hands to her breast in a credible imitation of Mrs. Siddons. “Don’t you think you owe me an explanation?”

Turnip knew the answer to that one. “No.” And then, since that sounded a little harsh, “But I will take you out for an ice later if you like.”

Sally narrowed her eyes at him. “Do you really think I can be bribed with an ice?”

“Yes.” That usually worked for him. The sweet tooth ran in the family.

“I’m not ten anymore, you know. Make it that blue enamel and seed pearl set in that shop on Milsom Street, and you have a deal. What do you want with Miss Dempsey?”

“It’s a surprise.” Turnip was seized with a sudden inspiration. “Maybe I want to talk to her about you.”

Sally made a scornful sound with her tongue and her teeth. Rude, but effective. What were they teaching her in this school of hers? Weren’t they supposed to be turning her into a young lady? “She doesn’t seem like your usual sort of flirt.”

Turnip regarded his younger sister with alarm. “What would you know about that?”

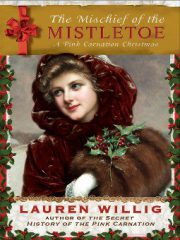

"The Mischief of the Mistletoe" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Mischief of the Mistletoe". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Mischief of the Mistletoe" друзьям в соцсетях.