“It was God’s will,” he said.

“And you have done your duty.”

“Under God’s will…that may be so.”

And, I thought, you have worn yourself out in doing so.

“Dear father,” I said, “you are unwell.”

“No,” he replied, “just tired. I cannot tell you how contented I am to sit here with you. You are a child no longer, Catherine.”

“I am eighteen years old.”

“It is an age of maturity. Do you regret that no marriage has been arranged for you?”

“No…I believe…”

“I know. You share your mother’s belief. She has always wanted you to marry into England.”

“It was talked of once.”

“That was long ago. It must have been more than ten years ago. Of a surety that was no time for the King to think of the marriage of his son.”

“No. It was a tragic time.”

“With an even more tragic end. There have been approaches, you know, but your mother has rejected them all. She cannot rid herself of the belief that you are going to England…and for that reason she has rejected all offers for your hand. I cannot understand her. It is a kind of dream of hers. It is so unlike her to cling to fancies.”

“I think I understand,” I said.

“I have been the most fortunate of men in my marriage, and I trust when the time is ripe you will find a partner who is as good to you as she has been to me. My greatest regret has been that I have had to be away from you for so long. I have had too little of my family and too much of war.”

“It has been a sadness for us all, dear father. But you are here now.”

“For a short time. I confess to you, daughter, while we are alone, that I should have been a happier man if I had not been a king. Now let us talk of other matters. You are eighteen years old — as I said, an age of maturity and wisdom.”

“I feel sure I fall short of the last.”

“You are as I would have you, my daughter, and to show my love for you, I have gifts for you. I propose to put certain lands into your possession. First, there is the island of Madeira. It is a beautiful spot, fertile and temperate. The city of Lanego is also to be yours, with the town of Moura. There will be tributes from these which will come to you.”

“But, father, it is too generous…I do not need…”

“My dear daughter, you are a child no longer. You need independence and security. So…they will be yours. But we must remember that they belong to Portugal and if you should marry out of the kingdom you would perforce relinquish these. On the other hand, if you married some Portuguese nobleman they would remain in your possession.”

I saw that my father thought this would be my eventual fate…if I married at all; and he wanted to assure himself that I was in the possession of independent wealth.

It was good of him, but I, with my mother, shared the feeling that one day I should go to England. I was, though, deeply touched by his generosity and care for me.

I told him this.

“I want you to be happy,” he said, “whatever may befall you.”

It was only a few months after that when he died.

IT WAS MORE THAN the loss of a beloved parent. The court was thrown into turmoil. My brother, Alfonso, at thirteen, had few of the qualities necessary to a ruler. There was rejoicing in Spain, where they must have been assuring themselves that it would not be long before Portugal was once more their vassal.

They had reckoned without my mother.

She said firmly: “I shall complete the work my husband has begun.”

Our people had always been aware of her strength and many of them knew of the part she had played in my father’s successful campaigns. She was without hesitation proclaimed Regent and the Spaniards’ jubilation was short-lived. Very soon they began to realize that they had little cause for rejoicing. Donna Luiza, Queen Regent, was not only a leader of resolution and dedication, she was a shrewd and skillful politician. My father had been right when he had said she should. And now she was the ruler.

She was more decisive than my father had been, less sentimental, more ruthless. Our armies were more successful under her direction and the government more secure.

Within two years of her dominance, Portuguese independence from Spain was established and there was growing prosperity throughout Portugal.

We now had some standing in Europe and Donna Luiza was one of its most respected sovereigns.

There were two offers for my hand which my mother feigned to examine with care, but nothing came of them. My worth had risen. Alfonso might not be recognized universally as king, but my mother could not be ignored; and her daughter was considered an important match.

And I was getting older.

“Is there never going to be a marriage for the Infanta?” my ladies were asking each other. “Is she going to spend her days as a spinster in Lisbon?”

I wondered, too. But the dream was still there, incongruous though it might seem. Charles, King of England in name only, was still wandering about the continent, flitting from court to court in search of hospitality. The Puritans still reigned in England. Charles was getting older, as I was — and we were still apart.

And then one day my mother sent for me and she said, with an excitement rare in her: “There is news from England. Oliver Cromwell is dead.”

I stared at her in amazement. “Does that mean…?”

“We shall see,” she replied. “His son Richard will succeed him. Oliver Cromwell was a strong man.”

“And Richard…?”

“It is not easy to follow a strong man. People want change. Whatever they have they dream of something different. They believe that what they cannot get from one they will get from another. Then the disappointment comes and the desire for change.”

“Do the English want change?”

“I am not sure. They are not a puritanical people by nature and are inclined to be pleasure-loving and irreligious. It surprises me that they have endured Puritan rule for so long. But Oliver Cromwell was such a strong man.” There was a grudging admiration in her voice which she tried to suppress.

“We shall see, daughter, we shall see,” she went on.

There were plans in her mind. I knew it. I wanted to talk to her but she would say no more. She was not given to speculation. She just wanted me to know that it would not altogether surprise her if the death of Oliver Cromwell was significant, and perhaps it would not be long before there were changes in England.

I was thinking of Charles more persistently than ever.

MY MOTHER HAD BEEN RIGHT when she said it was difficult to follow a strong man like Oliver Cromwell. He had died on the third of September of that year 1658, and less than two years after his death the King was restored to the throne.

Richard Cromwell, who followed his father, it appeared, was of a likeable nature. Perhaps the same could not have been said of his father, but Richard was pleasure-loving, fond of the sporting life and prone to extravagance, which led to trouble with his creditors. He was certainly no Oliver Cromwell.

The English were restive. Under Oliver Cromwell they had been kept under control. Now the resistance grew. The truth was that they were tired of Puritan rule, which was alien to them. It must soon have become clear that the majority of them wanted the return of the monarchy.

Charles was in Breda when an emissary was sent to him to discover whether he would come back to England and take the crown. With the offer came a gift of 50,000 pounds, that he might discharge any debts and equip himself for the journey.

I can imagine his joy. He was now asked to accept that for which he had fought and struggled for more than ten years.

He accepted with alacrity.

And what a welcome he received! I could picture it all so clearly when later he talked to me of that day. I know he never forgot it.

The people were exultant. I can picture his riding among them. He would have looked — all six feet of him — the perfect king. I knew how he could mingle that quality of regality with familiarity which enchanted all. I doubt whether there was ever a king of England so loved by his people.

He always called himself an ugly fellow, and when one considered his features that could be true, but his charm was overwhelming. There could never have been a more attractive man. I know that I loved him and one is apt to be unaware of the faults of the object of one’s devotion, but I can vouch for it that I was not alone in my opinion.

He used to talk of the ringing of bells, the flowers strewn in his path, the women who threw kisses at him, the shouts of loyalty.

“Odds fish!” he said. It was a favorite oath of his. “They gave me such a welcome home that I thought it must have been my own fault that I had stayed away so long.”

But he was home, and from that moment the excitement grew.

My mother was exultant. She had known, she said, that this must be. She had planned for it since my seventh birthday when the matter had first been raised. Keeping me from suitors, which had amazed so many, had proved to be right. She had not been fanciful, as so many had thought. She had been shrewd and realistic. She had one regret — that my father was not alive to see how she had been vindicated.

But we were not there yet. A king restored to his throne, fêted by his people, having learned the lesson of his father’s downfall, being determined — in his own phrase—“never to go wandering again,” seemed secure on the throne. He would need to be married, of course — and such a king was a very desirable parti.

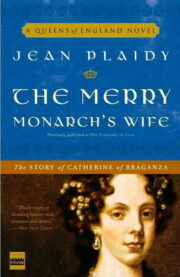

"The Merry Monarch’s Wife" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Merry Monarch’s Wife". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Merry Monarch’s Wife" друзьям в соцсетях.