One of the most lovable facets of Charles’s character — which I was to discover later — was his lack of dogmatism and his tolerance of the views of others. It was really due to the fact that he had an inherent abhorrence of conflict; he hated trouble and difficulties were often smoothed over in order to avoid it. He was lazy in a way; he liked life to flow smoothly. He immediately confirmed that I should have freedom to worship and I might have my own chapel fitted up wherever I lived.

My mother was immensely relieved.

But no sooner had that matter been settled than a more serious one arose. It was from Donna Maria that I first heard of this.

“There will have to be a proxy marriage,” she said. “You cannot leave the country without it.”

“Why not?” I asked. “I am going to marry Charles. Why should I need a proxy?”

“The King cannot come here and you cannot go into a strange country as an unmarried woman.”

“What harm would it do?”

“My lady Infanta, you are very innocent of the world. Unprotected virgins do not leave their homes unless chaperoned.”

“I should be surrounded by attendants.”

“How could we know what might happen to you?” she said mysteriously.

“Well, there will have to be a proxy marriage, I suppose, but it seems unnecessary.”

My mother was even more concerned than Donna Maria, but for a different reason.

“But why?” I cried. “You have the King’s letter. He says he is sending the Earl of Sandwich to take me back to England.”

“There should be a proxy marriage first,” said my mother.

“Well, there will be a proxy marriage. Is that so difficult?”

“If everything were as it should be there would be no difficulty,” she said. “But if you are married by proxy, it will be necessary to get a dispensation from the Pope because your husband is a Protestant.”

“Does that mean waiting?”

“It is not that so much which makes me anxious. The Pope does not recognize you as the daughter and sister of kings. He will give the dispensation; he would not dare offend Charles by not doing so, but at the same time your name will appear on it as the daughter of the Duke of Braganza, and that is something I will not allow.”

“What shall we do then?”

“There is only one thing we can do, and I do not like it overmuch.”

“What is that?”

“You must go to England without having a proxy marriage first.”

I smiled. “I think we need not worry about that,” I said. “Charles has said he wants me to go to England to marry him.”

She looked at me searchingly, and I thought she was about to tell me something; but she evidently decided not to. She merely nodded and said: “Well, there cannot be a proxy marriage.”

I did not attach too much importance to this. I was going to England to marry Charles after this long delay, and I was very happy about that.

DISPATCHES ARRIVED FROM LONDON which made me realize more than ever how very important it was for me to marry Charles, apart from my own inclination.

There were riots in London. These had been inspired by none other than the villain Vatteville, who had circulated rumors that if the King married a Catholic there would be trouble in England. Had the people forgotten the days of that Queen whom they knew as Bloody Mary? Did they remember that the last queen had been a Catholic? They were ready to blame Henrietta Maria for what was beyond her control. But it served a good reason for objecting to me.

For Vatteville and his master to act in this way was certainly ironical. They themselves were ardent Catholics. Why did they campaign against me? The answer was obvious. What they wished to avoid above everything was an alliance between England and Portugal.

The King and his ministers acted promptly. They had long become weary of Vatteville’s meddling. He was found to be in possession of subversive papers when his lodgings were searched, and was forthwith ordered to leave the country. Even then he tried to stay, to plea his cause, but Charles was tired of him, and refused to see him.

It was a great relief to know that Vatteville was no longer in England.

My mother said: “The fact that the Spaniards have shown themselves so eager to stop the match will make the English realize how important they think it. That is all to the good.”

As for me, my joy was complete, for I had received a letter from Charles. It had had to be translated, for it was in English, and I shall always treasure it. I know it by heart.

It ran as follows:

My Lady and Wife,

Already, at my request, the Conde da Ponte has set off for Lisbon. For me the signing of the marriage has been a great happiness; and there is about to be dispatched at this time after him, one of my servants, charged with what would appear to be necessary; whereby may be declared on my part the inexpressible joy of this felicitous conclusion, which when received will hasten the coming of Your Majesty.

I am going to make a short progress into some of my provinces; in the meantime, whilst I go from my most sovereign good, yet I do not complain as to whither I go; seeking in vain tranquillity in my restlessness; hoping to see the beloved person of Your Majesty in these dominions, already your own; and that, with the same anxiety with which, after my long banishment, I desire to see myself within them; and my subjects desiring also to behold me amongst them, having manifested their most ardent wishes for my return well known to the world.

The presence of your serenity is only wanting to unite us, under the protection of God, in the health and contentment I desire. I have recommended to the Queen, our lady and mother, the business of the Conde da Ponte who, I must here avow, has served me in what I regard as the greatest good in this world, which cannot be mine less than it is that of Your Majesty…

The very faithful husband of Your Majesty whose hand he kisses.

Charles Rex

London, the 2nd of July, 1661

It was the perfect love letter and I felt ecstatically happy.

I am glad I did not know then that after he had written this, he went off to spend the night with the woman who was to prove one of my greatest enemies.

THE MARRIAGE TREATY had been ratified and it was my mother’s wish that in our court I should be known as the Queen of England. I emerged from my sequestered life as an unmarried Infanta and had a place beside my mother, my brother King Alfonso, and the Infante Pedro.

“It would be well to leave before the winter comes,” said my mother.

But the winter came and still the Earl of Sandwich had not arrived with his fleet which was to take me back to England.

It would be too late now to leave before the weather made the journey too hazardous. Christmas had come and gone and I was still waiting.

“It cannot be till spring now,” said my mother. She was anxious. The Spaniards were augmenting their forces on the frontiers. There had been so many delays. People were beginning to say the match would never take place.

It was a time fraught with apprehension. I was glad I did not know to what ends my mother had to go to make sure we had had adequate defence against the enemy — but I was to learn of this later.

I remember well that joyous day.

It had been preceded by the deepest anxiety. Spring had come and Spanish ships were sighted off the coast. The attack was imminent.

I could see the despair in my mother’s eyes. She had been so certain of her wisdom in keeping me as a wife for Charles as the means of saving my country; she had been so sure of success; and now it could be that, because of these delays, all her hopes were foundering. If the Spaniards attacked now we could not resist them. Would the King of England want to marry the daughter of a defeated country, a vassal to Spain? In any case, the King of Spain would not allow the match.

I knew she prayed for a miracle — and her prayers were answered.

Spanish ships were preparing to land when those of the English fleet, in the charge of the Earl of Sandwich, came to take me back to England.

It was a triumph for us and defeat for the Spaniards.

Those Spanish sailors remembered the stories of the little English ships which routed the mighty armada of Spain. Their grandfathers had told them of that misadventure. They had told of El Draque, who was no ordinary man — a giant, a dragon, possessed of unearthly powers. Only such could have destroyed the great armada.

The Spanish ships made off with all speed and the troops massed at the frontiers could not act without the supplies of ammunition they were bringing. They could only disperse — and we were safe.

Lisbon went wild with joy. Bells were ringing and crowds gathered on the shore to greet the English ships.

“Viva il rey di Gran Britannia!” cried the people.

My mother’s relief was immense. The Earl of Sandwich must be given a royal welcome. Alfonso must send the Comptroller of the Household out to his ships; there must a twenty-seven-gun salute; the Earl must receive the warmest welcome possible from a grateful country.

There must be rejoicing. The finest apartments were prepared for him; there should be the grandest of banquets and the best bulls must be brought out for his entertainment. The anguish of uncertainty was over. The marriage could not fail to be celebrated now.

I did notice that after the first great relief my mother still seemed anxious. I wondered why this could be and, buoyed up by my newly acquired status — after all, I was styled Queen of England — I had the temerity to ask her what was wrong.

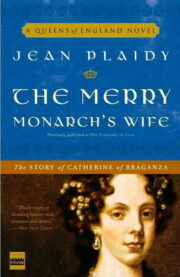

"The Merry Monarch’s Wife" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Merry Monarch’s Wife". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Merry Monarch’s Wife" друзьям в соцсетях.