“See?” murmured Augustus. “You’re far too much in demand. I won’t have five minutes without someone dragging you away for a game or a gossip.”

“I’m not so much in demand as all that. We could speak here. There’s no place so private as among a crowd.”

A yard from them, Caradotte crashed onto the turf, triumphantly raising the guitar in both hands. “Nice try!” he yelled back.

“Doesn’t someone want to call him out?” a lady called out from her semi-prone position on a blanket.

“Lutes at ten paces!” shouted someone else.

Augustus didn’t need to say anything. His point had been made for him.

Emma sighed. “We could go to the theatre.”

The minute the words were out of her mouth, she knew she had made a mistake. They stared at each other for an awful, frozen moment. The last time they had been in the theatre together—well, the less of that, the better.

“The front of the theatre, I mean,” Emma babbled. “The large part with the stage in it.”

“Er, yes,” said Augustus, and Emma felt her cheeks going even redder. What was wrong with her? She had managed to conduct an entire affair with Georges with complete sangfroid, and an accidental kiss had her bumbling and babbling. “I did rather get that. Miss Gwen is rehearsing her pirates. Remember?”

“That’s right.” Emma seized on the distraction with relief. “What was it she called them? She said they were insufficiently fearsome.”

“I believe the exact phrase was couldn’t pillage their way out of a wet paper parcel,” said Augustus delicately.

They grinned at one another, completely in accord.

Emma felt something catch at the back of her throat. She had missed him. She had missed this. Which was absurd, she knew. How could you miss someone when you hadn’t been apart?

“I never understood why they were in that wet paper parcel,” Emma said, her voice constricted. She cleared her throat. “It sounded like a very uncomfortable venue.”

“Perhaps they couldn’t afford a proper ship,” suggested Augustus. “They might be penurious pirates.”

“You’re alliterating again,” Emma pointed out. “You needn’t do that with me.”

They had been strolling rather aimlessly along the side of the house, but at that, Augustus paused. “No,” he said. “Not with you.”

There was a strange note in his voice. Emma let her own steps dawdle to a halt. She looked up at him quizzically. He was looking at her, none of the usual mockery in his face. There were twin furrows between his brows, and he suddenly seemed older than she had thought him to be.

“What is it?” she asked. “What’s wrong?”

Whatever it was, he thought better of it. He shook his head, moving briskly along. “Where shall we go? The back of the house is occupied and the house itself is swamped with people.”

Oh, yes. Their mysterious talk. Despite her growing unease, Emma strove to keep her voice light. “I draw the line at the stables. And the gardeners are very protective of the greenhouses.”

Augustus didn’t look at her. “What about the rose garden?”

It wasn’t an unreasonable suggestion. Leaving aside the romantic connotations of roses, it was well away from both the revelers in the back and the pirates in the theatre. A long alley of trees led down one side, shading the area and separating the roses from the bustle of the drive. It was as private as they could hope to be, with only one small caveat.

“Is the Emperor working in the summerhouse?” Emma asked, as they turned their steps in that direction. “If he is, we might want to stay out of the way.”

“Summerhouse?”

She’d forgotten that Augustus didn’t know Malmaison. Sometimes, it felt as though he had always been there. “It’s at the end of the alley,” said Emma, “just past the roses. On fine days, the First Consul—I mean, the Emperor—brings his work out there. As long as the windows are closed, we should be all right, though.”

“Mm-hmm,” said Augustus, which might have meant anything from yes to no to maybe. Emma took it as yes.

Emma glanced at Augustus’s shuttered face, doubly screened by the long fall of curly hair. One thing was certain: She wasn’t getting anything out of him until he was good and ready to speak.

They cut around the far side of the house from the theatre, along an alley of trees leading towards Mme. Bonaparte’s famous roses and the nondescript, octagonal façade of the summerhouse. Some of the roses, the earlier sorts, had already unfurled their petals to the sun. The leaves were stiff and glossy. There were rare and exotic varieties, Emma knew, smuggled in from all around the world, whisked into France in direct contravention of the blockades. The authorities knew to turn a blind eye when it came to Mme. Bonaparte’s garden.

Emma knew she ought to know more about it, to be able to appreciate the distinctions of this rose versus that, but her knowledge of horticulture was limited to “Ooh, aren’t the pink ones lovely!” A connoisseur might appreciate the niceties of specific species; Emma had only a jumbled impression of color and the heavy, heady scent of roses, all the more intense in the hazy heat of the day.

The low buzz of the bees was broken only by the sound of voices from the summerhouse, too low to be distinguishable, just loud enough to jar the peace of the garden. Emma could hear the earnest tones of Mr. Fulton’s voice, followed by the Emperor’s sharp bark, then another voice, softer, interceding. It must be very hot in there, with that many people crammed inside around the small table.

A bee bumbled past, drunk with pollen.

Emma looked at Augustus, who wasn’t looking at her. “All right,” she said. “We’re here now.”

Augustus clasped his hands behind his back. He paced towards the summerhouse, head bent, body angled forward, pausing for what felt like a very long while. The silence stretched between them, broken only by the staccato rhythm of voices from the summerhouse and the low hum of bees among the roses.

Emma’s skirt brushed against a rosebush, catching on thorns. She yanked it free again, making the flowers shake. The bee buzzed angrily and zigzagged away.

She knew how it felt.

The day was humid, despite the hot sunshine. Drops of sweat dripped down beneath her bodice, catching between her breasts. There would be a storm soon, if she wasn’t much mistaken. She could feel it in the prickling of the skin below her gloves, in the frizzled hairs at the nape of her neck.

“Do you have something to say,” Emma burst out, “or would you rather just stand there?”

For a moment, she thought Augustus might choose the latter. Then he turned abruptly on one heel. “Are you marrying your cousin?”

Emma gawped at him, the minor irritants of sweat and skin forgotten. “What?”

“Livingston,” Augustus said flatly. “The younger one. Are you marrying him?”

“It would be very hard for me to marry the older one,” said Emma sharply, “given that he’s been quite happily married since 1770.”

Augustus gave her a look. “That’s not an answer.”

“I’m not sure you deserve one.” Emma clawed at the itch on her arm, thwarted by her own gloved fingers. She squinted at Augustus, the sun full in her eyes. “I thought you were dying of a mysterious disease—or at least on the verge of fleeing the country. Instead, you drag me all the way out here to ask that?”

Augustus was dark against the sun. “Horace de Lilly told me you refused the Empress’s offer of a position in her household. Is it true?”

Emma raised a hand to shield her eyes. “What is this? Let’s interrogate Emma?” She was hot and itchy and irritable and unaccountably aggravated at Augustus, for reasons she didn’t quite understand and didn’t want to. “Yes. Yes, I did.”

He looked like Cotton Mather ready to cast out a sinner. “Because you’re going back to America.”

“Don’t worry,” said Emma flippantly. “I’m not going anywhere until after the masque is done. It won’t affect you.”

“So you are—” Augustus stumbled a step back, his expression a study in confusion. “I didn’t think—I didn’t imagine you would really—”

“Ever go anywhere?”

That was her, everyone’s friend, Mme. Delagardie, always there, always available, excellent for confidences, fine to kiss when one was disappointed in love, but have a life or a love of her own? Not likely.

“You didn’t imagine I would really what? Marry? I may not be your vision of Cytherea, but that doesn’t mean that no one wants to scale my tower.”

Lies, all lies, but she was too angry to care.

Augustus’s mouth opened and closed. Twenty-two cantos and she had rendered him speechless. “I never said that. I never meant—”

“You never mean anything,” retorted Emma. “That’s just the problem. Words, words, words, all sound and fury signifying nothing. Heaven help you if you ever had to shout for help. You wouldn’t be able to put it in less than five cantos. You’d be drowned before you got out the cry.”

Augustus ignored her ramblings. “Does he love you?” he asked in a low voice.

“Who?” She wasn’t sure why she felt the need to draw this out, but she did. Revenge, perhaps. Revenge for dragging her out here, for making her worry, for peppering her with inconsequentialities, for pretending he cared who loved her and who didn’t. What did it matter? He wasn’t offering to take up the torch himself.

“Livingston.” Augustus took a step forward. “Does he love you?”

Oh, Lord, why was she doing this? Emma pressed her eyes together so she wouldn’t have to look at him. The sun made strange patterns against the lids.

“As a cousin. He loves me as a cousin. That’s all. I’m not marrying him. I’m not going to America.” She forced out the words, tasting dust on her tongue, at the back of her throat. “Everything is exactly as it was.”

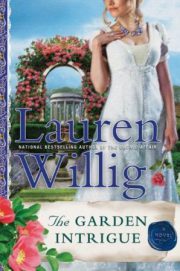

"The Garden Intrigue" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Garden Intrigue". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Garden Intrigue" друзьям в соцсетях.