“Just knock before you come in, okay? I’ll let Colin know that you might be in and out.”

“Thanks.” Cate glanced back over her shoulder. Even on the second floor, we could hear the sound of cars on the gravel of the drive, and voices from downstairs, steadily rising in volume. Either this was the catering crew, or some of the guests were arriving early. “I’d better get back down there. But I might sneak up later?”

“Any time,” I said, sliding into Colin’s desk chair. “We’ll be at the dinner, so the computer is all yours. You can ward off invaders for us.”

Cate brandished her clipboard. “Will do.”

“Don’t mind about the door. It”—there was a horrible squawking sound as she yanked at it—“sticks.”

“Sorry!” Cate’s voice floated back through the door panels.

My smile faded as I turned back to my e-mail. My open and maximized e-mail.

I might have just been careless and left the box open. But I didn’t think so. I was paranoid enough about Colin stumbling on that stupid 10B e-mail—not that it was really a secret, and I’d have to tell him eventually, anyway, but I’d rather tell him in my own time, once I’d figured out what I wanted to do.

Well, if Dempster had looked through my e-mails, he wouldn’t find anything of use to him, just details for my friend Alex’s engagement party, a few amusing forwards from Pammy, and those 10B e-mails.

I scrolled down the page. There were two new e-mails, one after the other. I’d shot off an SOS to two history department friends that morning, asking for advice. This wasn’t exactly the sort of dilemma with which I could go to my advisor. Archival issues, yes. Boy issues, no. Admittedly, this was a mixed issue of archive and boy, but it still smacked too much of the personal intruding onto the professional for me to share with anyone I wanted to take me seriously. So I’d appealed to Liz and Jenny instead.

Liz was my year in the history department, Jenny a year ahead of me. We had been dubbed the Triumvirate of Terror, not by the hapless undergrads to whom we had attempted to teach western civ, but by a colleague in the history department who had made the cardinal mistake of attempting to ask us each out, one after the other.

Our specialties were very different—Jenny did Charlemagne, Liz was all about madness in Renaissance Florence, and I had my thing for British spies—but we had formed a fast friendship that went well beyond complaining about undergrad essays and the lousy coffee in Robinson Hall. They were my favorite outlet shopping buddies.

They had both chimed in, Jenny from Cambridge, Liz from Florence, where she was on her research year. I checked the time stamp on Jenny’s e-mail. Wow. She really needed to stop getting up so early. Surely, Charlemagne could wait until a more civilized hour. He’d been dead about twelve hundred years, after all.

She wrote: My dearest Eloise, STAY IN ENGLAND! Really, why trade London for the joys of the Coop losing your book order and undergraduates whining that the B+ you gave them is the only thing standing between them and Harvard Law? Anyway, you found original documents. It is the Holy Grail of the historian. Stay and write them up! Boy or no boy, there will be plenty of time for teaching later. Liz and I will miss you, of course, but stay. Must run to Widener before it closes and then to Daedalus for drinks. More tomorrow. Love, Jenny

I regarded the e-mail with a warm glow. I love my friends.

I scrolled down through the e-mail chain to Liz’s feedback and my glow faded. Hey, snookums, wrote Liz. Is this about the boy?

Damn. She knew me way too well. I’d tried to couch it in neutral terms, making it out to be more about extra archival research than, well, Colin. But Liz was canny that way. She could smell ulterior motives on me like cheap cologne.

Funny, I’d expected her to be more pro, but the advice was decidedly pro-10B and anti-England. …don’t want to jeopardize your career for a guy…documents will still be there…brief research trips…if he really likes you, you can make it work long-distance.

Damn, damn, damn. One pro, one anti, and me still confused. I leaned my forehead against the heels of my hands, wondering how long I could reasonably put off replying to Blackburn. The sensible thing, of course, would be to talk it all through with Colin. He knew his archives better than I did. He could tell me whether there was sufficient material to make it worth my remaining an extra term—it didn’t need to be a whole year. I could go back to Cambridge for spring term and pick up my teaching duties then, even though it was unlikely a deal as sweet as the 10B head TF job would come along.

He could also tell me whether any of it was an option. He was, after all, a crucial part of the equation. Without a fellowship, my staying on would be predicated on his allowing me to live with him.

I thought of the poem Augustus Whittlesby had quoted to Emma Delagardie. “Come live with me and be my love.…”

Did Colin want me to come live with him and be his love and go through his archives? Or was that only for weekends and holidays, too scary to contemplate for daily use?

There was no way to find out except by asking him.

Like a petulant five-year-old resisting a nap, I didn’t wanna. Oh, I had any number of excellent excuses. Colin had enough on his plate, now wasn’t the time, I could wait until the film people left…But those weren’t the real reasons, sensible though they seemed. At base, I wanted Colin to say something without my having to. I wanted him to intuit what I didn’t want to ask. I wanted him to want me just because he wanted me, and not because it was a choice between inviting me to stay or my going thousands of miles away.

If only real life actually worked like that. In fiction, the hero’s declaration always comes in just the nick of time; the heroine doesn’t have to scrounge and maneuver for it.

My friend Alex, who had been in a functional relationship longer than anyone I knew, claimed that it didn’t have to do with their not caring; it was just the way they were wired. Men, that is. According to Alex, when they were least communicative was often when they were most content, happy, in ways we were not, just to take a good thing as a good thing and let it meander along its own course. In other words, the ultimate exposition of “If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.” We fretted about what they were feeling; they were wondering about dinner.

In this case, that was probably literally true.

Crap. How was it ten to seven already? Cocktails started on the dot and I was still in jeans and a ratty old button-down shirt. I kicked back out of Colin’s chair.

Dinner and Dempster first, major relationship issues later. Fortunately, Colin’s study was just down the hall from the bedroom we now shared, at least on weekends. My jeans and sweaters were slowly making inroads into the drawers, and my brush, earring collection, and deodorant had colonized a corner of the dresser.

Colin had already come and gone, judging from the clothing on the floor and the toothbrush dripping next to the sink. Damn. I had hoped to catch him while he was changing, in that intimate never-never land of shirt studs and tie loops, breaking the Dempster news to him while he was still in dishabille. Whispering it under the curious eyes of Colin’s evil stepfather and assorted Hollywood luminaries was going to put distinct limits on our ability to discuss.

I glanced at the door, but it didn’t obligingly open with a Colin on the other side of it. Okay, I’d just have to dress like the wind and catch him downstairs. At least I didn’t have much wardrobe to dither over.

I yanked my two cocktail dresses out of the closet. A life spent among the documents of dead people did not exactly prepare one for dinner with Hollywood’s finest. My wardrobe choices were distinctly limited. If I had thought ahead, I could have hit up my friend Pammy for an outfit. As a PR person—and an unabashed trust-fund baby—Pammy’s closet made Madonna’s look tame. Don’t even ask me about the hot pink yak-skin corset.

As it was, I had two choices: black or beige.

I reached for the beige. It was the closest to a designer article of clothing that I owned, made of soft mock suede with a fringed neck and hem, embroidered with a smattering of turquoise beads. A flap across the back tied at a diagonal angle, leaving a triangle of skin bare. It was a little bit Flintstones, but if all the guys I knew who had crushes on Wilma were anything to go by, that wasn’t a bad thing. Plus, it had certain sentimental associations. I had worn the same dress to a certain absurd party thrown by Pammy the night I learned that Colin was, in fact, single, available, and most likely flirting.

That had been one fun night, despite having to hold his sister Serena’s head over a toilet bowl when some dodgy prawns caught up with her.

I twisted my arms behind my back, struggling with the tie, which had the dual disadvantage of being leather and at an odd angle.

That had been the first night I had spent real time with Serena, who had also, because my world was that small, gone to school with my old friend Pammy. It had been the night Pammy had dropped the bombshell that Serena wasn’t, as I had erroneously presumed, Colin’s girlfriend but his sister, and that his solicitous attention to her was the result of her having just gone through a particularly nasty—

Oh, God.

I froze, my arms bowed out behind my back. Breakup. She had just gone through a nasty breakup with Nigel Dempster. That had been back in October. Dempster had broken up with her in September. He had made a play for me in November. Serena and Colin had functionally stopped speaking in March, when Serena threw in her vote with Jeremy in exchange for a junior partnership in the gallery where she currently worked. In the past two months, all we’d heard about her had come, piecemeal, from Pammy or from Colin’s aunt Arabella, who, while disapproving, had chosen not to kick the erring ewe from the fold. But those snippets hadn’t been much; Colin tended to get tight-lipped and walk away when Serena came up. He had even done that to me a time or two. Her betrayal had cut deep.

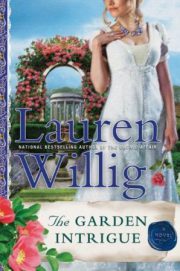

"The Garden Intrigue" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Garden Intrigue". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Garden Intrigue" друзьям в соцсетях.