Oh, good. Now she didn’t sound brusque. She just sounded like the village idiot.

Mustering her wits, she said, “Either way, I’m sure it will go splendidly. How can it not with my imagination and your pen? Everyone will be shouting for encores!”

She looked expectantly at him, but Mr. Whittlesby was not inclined to match her cheerful tone. “How long have you known?”

“Since Friday.”

“Friday?”

“I should have thought you would be glad to have Miss Wooliston in our cast,” said Emma, nettled past tact. “It will save you the bother of following her from place to place.”

Well, that got his attention. But not in a good way. From the look he gave her, one would have thought he had just caught her going through his jacket pockets. If he ever wore a jacket, that is. The billowy linen shirt left little to the imagination.

Emma colored. That was always the problem with fair skin—the slightest hint of embarrassment and there it came, out like a rash. But, really, there was no reason to be made to feel as though she were somehow rooting about in his private affairs. He had made his feelings for Jane entirely public.

Twenty-two cantos of public.

“You’re never going to win her that way,” said Emma officiously.

Whittlesby’s face was a study in outrage. “I beg your pardon?”

“You ought,” said Emma frankly. “All those cantos, all those readings, and all of them for nothing! It’s been very tedious.”

“No one asked you to subject yourself to my work,” said Whittlesby loftily. “They were not intended for you.”

“Please don’t misunderstand me,” said Emma. “I don’t mean to malign your poetry. It’s simply that as a technique for courtship, it leaves something to be desired. I know they say poetry is the way to a woman’s heart, but it didn’t work for Petrarch, either.”

“Has it occurred to you, madam, that I might write verse for the sake of verse? That the creation of poetry might in itself be the object of desire rather than the fallible human form that inspires it?”

Yes, but Jane had a very lovely form, and she had several years yet before it started to be fallible. Oh, the joys of being twenty-two and in little need of corsets!

“That is nicely said,” said Emma approvingly. “For your sake, I hope it’s true.”

“My intentions,” Whittlesby said with dignity, “are as pure as my poetry.”

“It isn’t your intentions that are the problem, but your methods. Twenty-two cantos? There are far better ways to get a lady’s attention.”

“Are you offering to play Cyrano?” There was a decidedly dangerous glint in Mr. Whittlesby’s eye. “Don’t confuse me with your Mr. Marston. Not all men are in his mold.”

“You mean, direct?” Emma wasn’t quite sure why she was defending Marston, other than that, at this particular moment, she would have negated anything Whittlesby said, up to and including green being the color of grass and the sky being up rather than down.

“Direct,” Whittlesby repeated. “That’s one way of putting it. Direct to your door?”

Emma flushed. “At least he made clear what he wanted.”

Whittlesby’s eyes narrowed on her face, taking on a speculative expression. “And what might that be?”

“Didn’t you know?” said Emma, with a forced laugh. “My diamonds. Pity for him they’re paste.”

She didn’t want to talk about Marston with Augustus Whittlesby. She didn’t want to talk about Marston at all.

Behind Whittlesby’s shoulder, a young man was hovering, dressed richly in a deep green jacket with a waistcoat in stripes of pink and green.

“Oh, look,” she babbled, waving enthusiastically, “there’s dear Monsieur—”

What was his name? There had been so many people come to Paris recently, so many members of the old aristocratic families returned from exile in England and elsewhere. It was impossible to keep them all straight.

“De Lilly?” Whittlesby frowned over his shoulder at the young man.

“Yes?” At the sound of his name, the young man hastened forward. It hadn’t been meant as an invitation, but he took it as such. He bowed enthusiastically over Emma’s hand. “Madame Delagardie! It is a pleasure.”

At least someone thought so. Emma tried to send a meaningful look at Mr. Whittlesby, but Mr. Whittlesby wasn’t paying the slightest bit of attention.

De Lilly was probably roughly her own age, but he seemed like a boy, all pink-cheeked and eager to please. He made Emma feel ancient.

“Do you know Mr. Whittlesby?” Emma asked de Lilly, mostly to needle the poet. She missed her fan. It was so much less effective gesticulating without one.

De Lilly glanced sideways at Mr. Whittlesby and went pink about the cheekbones. “Mr. Whittlesby and I are somewhat acquainted.”

Emma looked inquisitively at Mr. Whittlesby, but the poet had assumed his most otherworldly expression.

“The muses lead many to my door,” he intoned.

De Lilly dropped his gaze to his boot tops, looking sheepish and very, very young. “Mr. Whittlesby was kind enough to undertake a small commission for me.”

Emma glanced archly at the poet. “Service à la Cyrano?”

Mr. Whittlesby sniffed. “If you insist on calling it that. I prefer to think of it as wooing for the romantically impaired.”

De Lilly went an even deeper red.

Oh, the poor thing. Emma felt guilty for having pushed the topic. If only her mouth wouldn’t run ahead of her brain! There was nothing more painful than puppy love. Emma wondered who he might be in love with. There were so many candidates.

“It’s always useful to have a poet about,” she said to the young man. “Everyone is hiring them these days.”

“Er, yes.” He dragged his eyes up from his boots, clearly eager to change the topic. “Have you heard the news?”

“News?” Emma lifted a hand in response as her friend Adele de Treville waved at her from across the room. “Oh, do you mean that story about Mademoiselle George and the tenor? Or was it a flautist? I’ve heard it was vastly exaggerated, especially the bit about his being tossed into the Seine naked.”

M. de Lilly shook his head vigorously. “Oh, no. It wasn’t the Seine, it was the fishpond at Saint-Cloud.” There was a strange snorting sound from Mr. Whittlesby’s general direction. M. de Lilly glanced cautiously in his direction before going on. “But that’s not what I meant. Didn’t you hear?”

“Hear what?” asked Emma. If it was better than the flautist in the fish pond, it was bound to be good.

De Lilly drew himself up. “The senate has voted.”

As an attempted grand pronouncement, it fell rather flat.

“How nice for them,” said Emma. Didn’t they do that sort of thing rather frequently? “On what?”

Both men stared at her, united, for the moment, in mutual disbelief.

Mr. Whittlesby cleared his throat, shocked out of his offended silence. “Do you read anything except the fashion papers, Madame Delagardie?”

“Of course. I read Le Moniteur every day.” More like every month, but who was counting. She batted her lashes up at the poet. “How else would I know what my friends are doing?”

Bursting with his news, de Lilly ignored their byplay. “The senate voted,” he said loudly, “and Bonaparte accepted.”

His words were ostensibly directed at Emma, but his eyes were on Whittlesby.

“Should you like me to compose an ode for the occasion?” drawled Whittlesby, just as Emma demanded, “Accepted what?”

De Lilly turned to her, his eyes bright with excitement. “It’s official! Bonaparte is Emperor of the French!”

Chapter 12

What matter kings or princes bold?

Or belted earls with titles old?

All is mere pomp, none can display

The zeal that spurs me on my way.

What in the devil was de Lilly playing at?

Augustus tried to signal his young colleague, but it was no use. Ignorant pup, thought Augustus, too busy capering for a lady’s attention to weigh the risks. Fuming inwardly, Augustus pretended insouciance and mentally began composing a memo to Wickham, listing the various reasons why Horace de Lilly was unsuitable for assignment in the field.

Whatever reaction de Lilly had hoped to elicit, he didn’t get it. Mme. Delagardie blinked. And blinked again. “Emperor? As in…Emperor?”

Avoiding Augustus’s eye, Horace de Lilly nodded vigorously, focusing all his attention on Mme. Delagardie. “I hear you’re to be a lady-in-waiting, Madame Delagardie.”

“A—”

“Lady-in-waiting. It’s a great honor,” said de Lilly earnestly.

Mme. Delagardie didn’t look honored. She just looked stunned.

“My mother was a lady-in-waiting to the former Queen,” de Lilly said importantly, before hastily correcting himself. “I mean, the widow Capet. You’ll probably have an apartment in the palace. And another at Saint-Cloud.”

“Lucky me,” said Mme. Delagardie, with something like her usual frivolity. “What a pity I have a home already.”

Horace looked mildly horrified. “But it’s not about that,” he said. “It’s so you can be at court. It’s—oh, you’re joking, aren’t you, Madame Delagardie?”

“Mmm,” said Madame Delagardie.

“Darling!” Adele de Treville breezed past in a wave of perfume and burgundy silk. Like Mme. Delagardie, she was a widow about town, intimately connected with the Bonapartes and their circle. “I’ve been waving and waving to you from the other side of the room, but you’ve been too busy with this handsome thing to pay me any notice.”

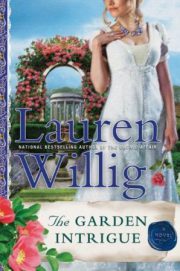

"The Garden Intrigue" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Garden Intrigue". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Garden Intrigue" друзьям в соцсетях.