Much heartened by this evidence of the beneficial effects to be obtained by treating his servants with brutal severity, the Duke hurried into his clothes, and had packed Belinda and her bandboxes into the chaise again before Francis had had time to return with the answer to his letter. So emboldened by his victory over Nettlebed was he feeling that he drove round to Laura Place with the intention of being extremely high-handed with the Dowager, if she should dare to thwart him. Happily (since the Dowager was more than capable of holding her own against far more formidable males than he would ever be), this trial of strength proved to be unnecessary. When he was admitted into Lady Ampleforth’s house, he found his Harriet already descending the stairs, with her hat on, and a cloak hiding her muslin gown.

He started forward to meet her saying: “Do you go with me? Will Lady Ampleforth trust you to me? How pretty you look!”

If she had not been in her best looks before, this impulsive exclamation naturally made her glow into something approaching beauty. She smiled tremulously, blushing, and murmuring: “Oh, Gilly, do I? I do not know how you can say so, when you have been with Belinda!”

He acknowledged the force of this, but said seriously: “I do not know how it is, Harriet, but I would rather look at you than at Belinda. You have more countenance!”

She now knew that whatever happiness might be in store for her this must rank as the most memorable day in her life. To conceal her swelling pride, she said in a rallying tone: “You are trying to flatter me, Gilly!”

“No,” he said. “I know you too well to suppose that flattery would be acceptable to you.”

Without making the slightest attempt to disabuse his mind of its curious misapprehension, Harriet said simply: “I am glad you think I have countenance, dear Gilly. I want only to be worthy of you.”

“To be worthy of me!” he said, quite thunderstruck. “But I am the most commonplace creature! Indeed, I do not know how you can look twice in my direction when you have known my handsome cousin!”

“Gideon?” she said in surprised accents. “Of course I have a great regard for him, for I am sure he has always been very kind, and you love him, which must recommend him to me, you know. But surely no one in their senses could think of him when you were by, Gilly!”

Preys to their blissful delusions, they walked slowly out of the house to the waiting chaise.

“I was half afraid your grandmama would not let you come with me!” the Duke said foolishly.

“Oh, Gilly, was it very wrong of me? I was obliged to use a little stratagem, for she was so cross, and I could see she meant to say it would be improper for me to go! I—I said I knew Mama would not permit it! Not quite like that, you know, but letting it be seen that that was what I thought. It is very dreadful! She doesn’t like Mama, and I knew very well that I had only to put that into her head, and she would say I might go with you!”

She sounded conscience-stricken, but the Duke laughed delightedly, so that any filial qualms that were troubling her gentle soul were instantly laid to rest. He handed her into the chaise, where Belinda greeted her without the smallest sign of guilt.

“Oh, my lady!” said Belinda. “Mr. Rufford—I mean, the Duke!—has found Mr. Mudgley!”

“Dear Belinda, you must be very happy!” Harriet said, laying a gloved hand on her knee.

“Oh, yes, ma’am!” agreed Belinda blithely. She paused, and added on a more wistful note: “But I wish I might have had that beautiful dress!”

“I am sure you would not wish for it rather than to be established so comfortably,” Harriet suggested gently.

“No, indeed! Only that I might perhaps have stayed until Lord Gaywood came back, you know. For he went to buy it for me, and it does seem very hard that I must not have it after all!”

Harriet, quite dismayed, strove to the best of her ability to give Belinda’s thoughts a more proper direction. The Duke, a good deal amused, intervened, saying: “Useless, my love! If you would but do what you may to convince her that this last adventure must be kept a secret between the three of us, it would be very desirable!”

“It seems very dreadful to be teaching the poor child to deceive the young man!” Harriet replied, in an under-voice. “I own, it might be wiser—But to have a secret from the man to whom one is betrothed is very wrong, and surely quite against female nature!”

“Dear Harriet!” he said, finding her hand, and raising it to his lips. “You would not do so, I know! But if she blurts out the whole to these people—? For they are simple, honest folk, and could not understand, perhaps.”

“I will do what you think right,” she said submissively, and thereafter tried her utmost to impress upon Belinda the wisdom of banishing Lord Gaywood alike from her thoughts and her conversation. Belinda was so much occupied in ecstatically recognizing and pointing out to her companions remembered landmarks that it seemed doubtful whether she attended with more than half an ear to the kindly advice bestowed upon her, but she was a very persuadable girl, and by dint of Harriet’s dwelling strongly on her unfortunate contretemps with the Dowager she was soon brought to the conviction that her sudden descent upon Furze Farm was due not to any traffic with Lord Gaywood, but to her having broken a cherished Sevres bowl.

But when the chaise drew up by the farm, Harriet could almost have believed that these precautions had been needless. For Mr. Mudgley was just shutting the big white yard-gate, and he turned, and stood still to watch the chaise, with the setting sun behind him, striking on his uncovered head, and catching the auburn lights in his thick thatch of curly hair. He was still wearing his working-clothes, with his sleeves rolled up, and his shirt open to reveal the tanned, sturdy column of his throat, and he presented such a fine figure of a man that not even Harriet, with twenty years of strict training behind her, could wonder that Belinda no sooner saw him than she gave a little scream of joy, and, without waiting for the steps of the chaise to be let down tumbled headlong into his arms. It did not seem probable, after that, that any explanations would be asked for or proffered.

The Duke and his betrothed did not linger for many minutes at the farm. Mrs. Mudgley was sufficiently mistress of herself to do the honours of the house, but her son could scarcely be brought to take his eyes from his long-lost love, and Belinda, her eyes like stars and happy laughter bubbling on her lips, darted about, recognizing and exclaiming at first this object, and then that, and paid very little more heed to her late protectors than if they had been a part of the furnishings of the big kitchen.

“And I was conceited enough to fear that she liked me a little too well!” confided the Duke, once more bowling along in the chaise. “I am quite set down!”

“Do you know, Gilly,” said Harriet thoughtfully, “I am much inclined to think that Belinda is perhaps one of those people who are very pretty, and amiable, but do not care profoundly for anyone. It is very sad! Will Mudgley discover it, and be unhappy, do you think?”

“Why, no! She is good-natured, and affectionate, and although he may be an excellent fellow I do not imagine his sensibilities to be over-nice. They will deal very well together, I daresay. She will always be silly, but he appears to have considerable constancy, and we must hope that he will always be fond!”

Harriet, accepting what he said, was content to forget Belinda. She sat cosily beside the Duke, her hand in his, while the chaise covered the little distance between Furze Farm and Cheyney. He was tired, and she was happy; they exchanged few remarks, and those, for his part, in lazy murmurs. Once the Duke said: “Let us be married very soon, Harriet.”

“If you wish it, Gilly!” she said shyly.

He turned his head against the squabs that lined the chaise, and looked at her mischievously. “Of course I do. I see that you mean to be a very good wife, you are so conformable! Do you wish it?”

She nodded, blushing, and he laughed, beginning to tease her about the hats she must buy in Paris when it was discovered that those she had already ordered from Mrs. Pilling made her look like a dowd. She was still protesting when the chaise drew up before the doors of his house.

“I have no extraordinary liking for this house of mine,” the Duke said gaily, handing her down from the chaise, “but still I shall say Welcome to your home, dear Harriet! How strange it seems to be rid of all my embarrassments! I shall not know how to go on, I daresay!”

He led her up the few shallow steps to the doors. These were flung open to them by an embarrassment he had forgotten. The Duke paused, a rueful look in his eye, and exclaimed: “The devil! I must do something about you, I suppose!”

Mr. Liversedge had, naturally, no livery with which his office might be dignified, but the lack of it was scarcely noticeable. His carriage was majestic, and his manner to perfection that of a trusted steward of long standing. He bowed very low, and ushered the young couple into the house, saying: “I trust your Grace will permit me to say how very happy we are to receive you, and her ladyship! I venture to think that you will find everything in readiness, though, to be sure, as your Grace well knows, the staff at present residing here is of a scanty, not to say inadequate nature. I should add that Master Mamble—a good lad, but addlepated!—forgot to inform us that her ladyship would be accompanying your Grace. But I will instantly apprise the housekeeper of this circumstance. If your Grace should care to take her ladyship into the library while I perform this office, you will, I fancy, find the Captain there, and such refreshments as I ventured to think might be acceptable to you after the drive. Lord Lionel, I regret to say, stepped out a little while since with Mr. Mamble, not being in the expectation of receiving her ladyship. He will be excessively sorry, I assure your ladyship.”

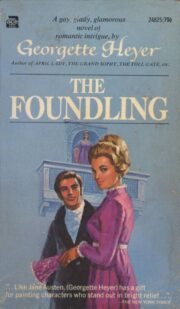

"The Foundling" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Foundling". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Foundling" друзьям в соцсетях.