“Strasbourg,” said the Duke meditatively. “I remember I disliked the place excessively. I was never more bored! I will revenge myself on Strasbourg, Liversedge, by sending you there to batten upon its citizens. But if any other peer should chance to come into your orbit again, do not kidnap him, for that might come to my ears, you know, and I should feel that it was time to make an end of you.”

He rose to his feet as he spoke, and walked towards the desk that stood in the window.

“Sir,” said Liversedge, “I am not of those who do not profit by their mistakes. In departing from an occupation at which I excel I erred. Kidnapping is too crude a trade for any man of taste and sensibility.”

“You are wise,” said the Duke. “If such a greenhorn as I could—”

“Careful, Gilly!” Gideon said under his breath, his eyes on the doorway. “The fat, I fear, is now in the fire!”

The Duke turned his head. Mr. Liversedge had neglected to shut the door securely upon his entrance into the library, and it now stood wide. Lord Lionel stood on the threshold, as though transfixed, an expression of such wrathful amazement in his face that any hope his nephew might have cherished that he had not overheard enough to make plain to him the whole died on the spot.

“So!” uttered his lordship terribly. “I am now in possession of the truth, am I? I might have doubted the fidelity of my ears had I not already had reason to suppose that you have taken leave of your senses, Sale! I came to find you, to request that you will give me an explanation—But that can wait! Give me a plain answer, yes or no! Is this the rascal who tried to hold you to ransom?”

“You know it is, sir,” said the Duke.

His lordship drew an audible breath. “If you have not actually lied to me, sir, you have practised the grossest form of deceit! I would not have believed you capable of it, for with all your faults—”

“Shall we leave my faults for discussion at some more convenient time, sir?” interrupted the Duke.

Lord Lionel was a just man. Even as he opened his mouth to blister his nephew he realized that the rebuke had been deserved, and shut it again. He said with strong restraint: “You are very right! You will not, however, expect me tamely to acquiesce in your extraordinary schemes! Don’t try to put me off, Sale! I came in time to hear more than enough! As well that I did so, since you have apparently succeeded in cajoling Gideon into permitting you to indulge your whimsicality in a manner—”

“What, in the name of all that is wonderful, have my affairs to do with Gideon?” demanded the Duke. “Indeed, what have they to do with anyone save myself? I am not a child, sir!”

“You are—” His lordship recollected himself, and stopped. He shut the door ungently, and strode into the middle of the room. “There has been enough of this nonsense!” he said. “If you cannot see what is the proper course to pursue, I can! This villain is to be handed over to those who will know how to deal with him! Either you will give orders for a constable to be fetched from Bath to take him in charge, or I will!”

The Duke moved to the desk, and sat down at it, and drew a sheet of paper towards him. “I have no power, sir, to prevent you from sending for whom you wish,” he said, his soft voice even, and rather chilly. “I think it only right to warn you, however, that I am making no charge against Liversedge, and shall deny whatever allegation you might feel yourself compelled to utter.

Gideon’s black brows went up, and one corner of his mouth too. He glanced at his thunderstruck parent, and said warningly: “’Ware riot, sir, ’ware riot, I do beseech you!”

“Be silent!” Lord Lionel rapped out. “Gilly, why!”

“I have already told you, sir,” the Duke replied, dipping a pen in the inkstand, and beginning to write. “I do not choose to advertise my own folly.”

Mr. Liversedge, who had been listening with an expression of great interest to this animated dialogue, coughed in a deprecating way, and said: “If I may say so, sir, such a decision is a wise one, and does you credit. It would indeed be undesirable to apprise the vulgar world of this affair. Setting aside all consideration of your dignity—not that I would for an instant advocate anyone’s doing so!—one cannot but reflect that the knowledge of my failure might inspire some more fortunate conspirator to lay a plot against your Grace that would achieve success. And that,” he added earnestly, “is a thing I should deprecate as much as the most devoted of your relatives.”

Lord Lionel brought his staring gaze to bear upon him. “Upon my soul!” he ejaculated. “This passes all bounds!”

It was at this inopportune moment that Mr. Mamble came into the library, rubbing his hands together, and saying with a satisfaction unshared by his hosts: “I thought I should find you here! Well, your Grace! Eh, but you look different than when I saw you in that shabby old coat you was wearing when I had you arrested for a dangerous rogue!” He chuckled at the memory, and advanced into the room. “Well, his lordship and I have become a pair of downright cronies, as I daresay he has been telling you. He has his notions, and I have mine, and maybe we’ve both learned summat we didn’t know before. But I’m fairly put out by that young rascal of mine! It’s mercy it was no more than a sheep, and your Grace kind enough to pardon it, else I would have dusted his jacket rarely for him!”

“How do you do?” murmured the Duke, half-rising, and extending one hand. “I beg you will forget the sheep! I stand so much in Tom’s debt that one sheep’s life seems a small price to be called upon to pay.”

“Well, I don’t know how that may be,” responded Mr. Mamble, shaking the hand, “but it wasn’t as bad as that! What’s o’clock? I’m beginning to feel sharp-set, I can tell you, and ready for my dinner. Ay, there’s the Captain pouring out the sherry, I see, and right he is! A glass of sherry is the very thing I was needing, for I’ve been riding out with your good uncle, your Grace, looking over your estate. It’s not so large as mine, by Kettering, but he tells me it ain’t more than a tithe of what you’re possessed of.”

Mr. Liversedge rose nobly to this as to every other occasion. He bowed politely to Mr. Mamble, sweeping him in some irresistible fashion known only to himself towards the door, and saying in a voice in which authority and civility were nicely blended: “I shall have a bottle of sherry sent up to your room, sir, on the instant. You will be desirous of changing your raiment before sitting down to dine with his Grace. The hour is already far advanced, but have no fear! Dinner will be held until you are ready to partake of it.”

Mr. Mamble might fancy himself to have achieved habits of easy intercourse with Lord Lionel, but he was not of the stature to compete with Mr. Liversedge, and he knew it. He allowed himself to be bowed out of the room, saying that he had not known it was so late, and must certainly change his dress.

Lord Lionel’s exacerbated feelings found relief as soon as the door was fairly shut behind him. “Intolerable upstart!”

Mr. Liversedge said soothingly: “I beg your lordship will not trouble your head over him! A good man in his way, but vulgar! One cannot but feel that his Grace was misguided in extending the hospitality of Cheyney towards him, but old heads, as your lordship well knows, are not found upon young shoulders.”

Lord Lionel found himself so much in sympathy with this observation that he was almost betrayed into applauding it. He stopped himself in time, and was just about to scarify Liversedge for daring to open his mouth, when the Duke spoke.

“Liversedge!” he said, shaking the sand from the few lines he had written.

“Your Grace?” responded Liversedge, turning deferentially towards him.

“You will accompany me to Bath this evening. I will furnish you with the means to buy yourself a seat upon the mail-coach to London. When you reach London, go to Sale House, and give this note to Scriven, my agent, whom you will find there. He will comply exactly with its instructions. I have requested him to advance you the sum stated in whatever coinage may be most convenient to you. Don’t delay to quit this country! I assure you it might yet become unfriendly to you.”

“Sir,” said Mr. Liversedge, taking the letter from the Duke’s outstretched hand, “no poor words of mine could convey to your Grace the sense of the deep obligation I feel towards you! I venture to prophesy that you will live to become an Ornament to the Peerage, and if—with my hand on my heart I say it!—I should not again have the felicity of setting eyes upon your face, I shall cherish the memory of my all too brief association with you to the day of my demise! And now,” he continued, tucking the Duke’s letter into his pocket, “I will, with your Grace’s permission, repair to the kitchens, where I dare not hope that my surveillance is not long overdue.”

With these words, the magnificence of which apparently made Lord Lionel feel that any attempt at expostulation must come as an anticlimax, he bowed again, and left the room with an unhurried and a stately gait.

“I am far from approving of your conduct, Adolphus, but I will own that I should be sorry to see your enterprising acquaintance in Newgate,” said Gideon. “He comes off with the honours!”

His father rounded on him. “How many more times am I to tell you not to call him by that name?” he demanded, venting an irritation of spirit that had no relation at all to anything Gideon had said.

“I must leave that to yourself to decide, sir,” replied Gideon, willing to draw his parent’s fire.

But the Duke intervened. “Oh, no, sir, don’t forbid him to call me Adolphus! He is the only person who does so, and how much I should miss it if he ceased!”

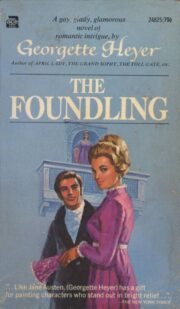

"The Foundling" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Foundling". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Foundling" друзьям в соцсетях.