It looks as though she wants to attack us but cannot decide which of us will be her target, me or Adair. He pulls me even closer to him to protect me, but that only elicits a howl of anguish from her. We can feel her gather strength, her unhappiness crackling the air like an electrical storm. “You will not try to hurt her again!” Adair bellows at her, holding a palm out against her. “If you do, you will answer to me.”

“She is the interloper here, not me. You are my husband, and nothing can change that,” she snaps at him.

“There is one way to change it,” Adair says, brightening as a thought comes to him. “I’ll abdicate.”

The queen draws back, aghast. Giving up power is unimaginable to her, I suspect. She regards Adair uncertainly, as though he’s just told her that gold is as common as sand and that stars are made of spun sugar. “It’s not a decision you can make on your own, and you know that. The father of the gods made you king, put you in this position himself. It will be up to him. He must decide to allow it.”

I can feel the tension in the air evaporate as they both back away from the brink of a fight. Adair lifts his chin when he addresses her. “Let the power above us all pronounce judgment on me in person. I want our father to tell me to my face what he would have me do. I swear I will submit to his will.”

His sister sniffs at him as though it is a trick. “You want him to settle this because you’ve always been his favorite. But I think this time, that’ll backfire on you. Being his favorite won’t save you. You’ve tested his patience once too often. So, I agree: you shall bring your case before him, and we will both abide by his decision. You have my word.” She doesn’t wait for Adair to agree or try to get out of the bargain. Before he can say another word, she disappears again in a puff of smoke, leaving Adair and me to blink at each other, unsure of what we have just agreed to.

TWENTY-THREE

After the confrontation with his sister, Adair senses that the underworld has been placed on a kind of lockdown. The castle seems to be holding its breath, cast in a groggy half sleep like something out of a fairy tale. When he tries to push back against the frosty stillness, it resists him, and this is how he knows it’s been imposed by someone more powerful than him.

He rattles down an empty hall, thinking about the challenge he threw down and all the possible ways it might go wrong. As for his sister, he’s not sure where she’s gone—off licking her wounds and plotting, most likely. Adair has hidden Lanore away in a secret room, which he has placed under his protection, wrapping it up with his intentions—this space is inviolate—like a spell, concentrating on it continuously, so that she will be safe from the queen, should she try some kind of sneak attack. But to protect Lanore like this takes up most of his energy and Adair can barely think or do anything else. He’s not sure how long he can keep this up.

Everyone has disappeared—the demons, the various servants—and Adair wonders if his sister has taken them away with her or if they’ve made themselves scarce, like animals anticipating a tornado. Even Jonathan has disappeared, though Adair figures he is with the queen. Adair suddenly wishes for Stolas’s company, remembering the old man’s canniness. He is a good tactician. But Adair knows he cannot pull Stolas from the pit without reducing his ability to protect Lanore, who is helpless without him. She waits in her hidden room like Rapunzel in the tower, dependent on her prince to figure a way out of this dilemma. Stolas must remain where he is for now.

Continuing on his solitary watch, Adair turns the corner to see an old man sitting on a marble bench. He’s familiar looking but Adair cannot put his finger on where he saw him last. (Ever since Adair returned to the underworld, he’s found that it’s like this with everything, the name of every sight, sound, and scent dancing just out of his reach.) The old man watches Adair as he approaches, smiling only at the last minute.

He wears toga-like robes as if he were an Olympian god and looks vaguely Greek or Roman. He has a beard and long hair, gray with streaks of white, and he wears it tied back in a loose ponytail, the way Adair often likes to wear his. Watching Adair approach, the old man doesn’t seem unkindly—nor does he seem to be anyone’s fool—he has a no-nonsense aspect about him.

When Adair draws close, the old man stands up and claps his arms around him. “Look who’s back. The prodigal son.”

Adair jerks in the old man’s embrace. The state of familial relationships on this plane has always been murky. The old man has been known to share his favors rather freely, and there has always been reluctance to spell out things like paternity. Adair remembers his long-suffering mother, remembers cherishing his relationship with that woman. The reserve he feels toward the old man probably has something to do with this. If the time has come that the old man wants to treat him as his son, then so be it, Adair decides.

The old man releases him and inclines his head toward Adair. By his weary reserve, Adair can tell that he felt Adair stiffen in his arms. He squints at Adair, sighs, and hooks his arm over Adair’s. As soon as the old man touches his arm, Adair feels an indescribable surge of power radiating through every cell of his being merely at the touch of his hand. “Come—walk with me,” the old man says.

They start down one of the dim, cavernous halls, the old man tut-tutting at the filth accumulated in the corners, the lack of light, the ugliness of it all. Still, he’s not presumptuous enough to change it with a wave of his hand, which he most definitely could. He could make it go away or replace it with trees and fountains, a park, or a ballroom complete with a brilliant white chandelier. “When was the last time you were here?” Adair asks as they walk.

The old man doesn’t need to think about his answer at all. “It was the day you left—or rather, disappeared. Your sister was very upset, you know.” He cocks an eyebrow at Adair, as if measuring his guilt.

Adair knows he should feel more sympathy for his sister. They were close once, confiding in each other, watching each other’s back. It never occurred to him that they might be paired together as mates, though there had been examples all around him, aunts and uncles, cousins who were part of the pack of young gods that ran around together. They did everything together: hunting, wrestling, playing, having fun. Then suddenly individuals would be culled from the herd only to reappear together as a pair and vaulted to the ranks of adults, put in charge of a realm, given attendant responsibilities. It was all very mysterious until the day the old man had come to him, clapped him on the back (not unlike what he was doing at this very moment), and told Adair he was going to become the king of the underworld, and that he’d have to take his sister as his queen.

“But why is it even necessary to have a king and a queen in the underworld? Why can’t I rule it alone?” Adair asks as they stroll slowly down the hall.

The old man turns up his palms, as if to say be reasonable. “Well, it’s a tremendous job, isn’t it? And one of the most important, too. We can’t have any mistakes made on this end, can we? It would lead to chaos. Must keep things moving in their proper order. Must keep the souls moving, sending energy back out to the cosmos. We can’t have someone too tenderhearted, mucking up the system. And because it’s all so important and so complicated, there has to be a backup, a deputy, in case anything happens.” Here, the old man gives Adair a fishy look, as though he suspects the ruler of Hades has stopped listening to him and is, instead, piling up more arguments in his mind.

“Then why can’t it be a deputy, or a lieutenant, just as you said? A second in command, instead of a mate. It could be run more like the military, or a business, rather than a royal kingdom. Why does it have to be a spouse?” Adair argues.

The old man lays his arm across Adair’s shoulders. “Being the king of the underworld is a very lonely position, my son. You’ve experienced that for yourself already. We’ve found that this way is best, having the pair work in tandem, closely. That way there’s almost no chance of something coming between them.”

A dark frown creases Adair’s face, his brow. “Why, then, I tell you, your system is already spoiled. I can never be close to her again, never. We will always be at each other’s throats.”

“Oh, don’t be so unreasonable. You’ve always been so dramatic—but then, I guess it is your nature. That’s the reason you were chosen for this position, you know. You were tailor-made for it, given to impatience. We knew you’d be perfect for it—your sister, too—and that you were made to rule together. Who else could we pair you with, anyway? You were both so troublesome, so argumentative. No one else would have you, either of you.” The old man chortled to himself, amused by his memories. “Anyway, as I was saying, it doesn’t matter if you can’t stand each other. Few of us can, you know. Husbands and wives—it just works out that way. Think of the old fellow, the one who ruled the underworld before you. Hades and his wife, Persephone. She couldn’t stand the sight of him. Eventually, she came around—enough to tolerate him, anyway. And they ruled a good long time. It’ll happen that way for you, too. You’ll see.”

Adair feels despair fill his chest. He’d promised to obey the old man’s decision and yet he knows he won’t be able to bear it. “No, it won’t be all right. I’m telling you, it won’t work out. You see, I’ve fallen in love.”

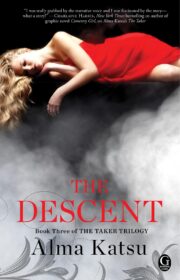

"The Descent" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Descent". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Descent" друзьям в соцсетях.