“How human you have become,” the old man says—and he doesn’t mean it in a good way. The gods think themselves above men. To be human is to be weak and concerned only about one’s self.

“I served you well in this position for a time, and you know it,” Adair reminds him. He has to be careful; he can’t risk making the old man mad at him. He needs the power above them all to release both him and Lanore from the underworld, as he’s the only one who can. Adair knows they would not make the journey through the abyss.

He needs the old man, but at the same time, his famously short temper is burning up like a lit fuse. “You’ve always said that this is the hardest job in all the heavens. I’ve done my share: now is your chance to prove your generosity by granting my release.”

“And what about your sister?” the old man counters wearily. “One could argue that she’s served me more faithfully than you. She never ran away. She held down the fort while you shirked your responsibilities. Why shouldn’t she be the one to get what she wants?”

“You’re right; I left my post, but I did so out of principle. I could not wed my sister. And now I have fallen in love. Haven’t you always said that love is your most perfect creation? That of all the things you made for man, love was your crowning gift? Why should only men be allowed to fall in love? Why should your greatest gift be reserved for men and not shared with the gods? You cannot fault me for falling in love. My sister is good and acting out of duty, but she isn’t in love with me. Give her the chance to fall in love, too.”

Exasperated, the old man throws up his hands. “I should have made you the god of oratory and not the underworld. Tell me, what would you have me do?”

“Let us go,” Adair implores. “Send us back. We’ll live out our lives quietly among the mortals. You’ll never hear from us again.”

“And your sister?” he asks gruffly. “What about her? Is that really fair to her?”

Adair hangs his head. For that, he has no answer except that unfairness comes to all of us. For a god, she is young and her story isn’t finished being told.

Changing his tactics, Adair asks, “Do you know what the difference is between man and god?” The old man shakes his head. Adair continues, “If it is within their power, most men will make the most humane choice every time. Not the ideal choice, perhaps, but the one that results in the greatest kindness. Whereas a god will not be swayed by humanity. An entire village will be wiped out by a tsunami, an entire race eradicated by disease or pestilence, if that is what fate demands. The gods are bound to uphold fate. We are slaves to fate.” He knows the old man has made plenty of decisions like these, and even though he is a god, such inhumanity takes its toll. “For once in your life,” he begs, “make the humane choice. Show compassion.”

The old man shakes his head at Adair, dismayed. “You never would’ve shown compassion, in the past. You were the epitome of a god, my boy. Unswayable.”

“And I was wrong.”

The old man scratches the back of his head, shoulders rounded in a shrug. “You’re putting me in a very bad spot.”

Adair embraces him one last time, their whiskery cheeks brushing. “I put our fate in your hands. I trust you will do the right thing.” After all, what are gods for if not miracles?

“Is that it?” I ask Adair when he returns to the magically suspended room a few minutes later. “How will we know what he’s decided? When will we know that he’s made his decision?”

He is much calmer than I imagine possible and I want to interpret this as good news. Adair wraps an arm around my shoulders and squeezes me tight to him. “I have to believe that he’s already made his decision, or otherwise—take it from me—things would’ve gone much more badly.”

TWENTY-FOUR

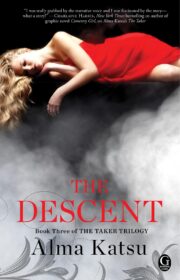

"The Descent" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Descent". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Descent" друзьям в соцсетях.