So much for Geoff building a future out of a pair of fine eyes. I had spun a fable out of a handsome face, a cute accent, and a few chance references that happened to resonate with me. Taken apart, bit by bit, my treasured hoard of memories was as tarnished and trumpery as a child's ring fished out of the bottom of a cereal box. So he had mentioned Charles II. Big deal. We were in England; unlike America, one could expect a certain basic familiarity with the country's more notorious monarchs. I had fallen, I realized, into that horrible, early stage of crush where everything becomes a point of commonality. If he compliments a song, your heart takes wing because, yes, you like music, too! Clearly, you are Meant to Be.

As one of my college roommates put it after I had run through a breathless round of perceived similarities that didn't mean much of anything at all, "Ohmigod! He breathes! And you breathe! It must be love!"

I hadn't succumbed to one of those all-consuming crushes since college. I had assumed it was one of those things one suffered through once and then got over—like the chicken pox. Unpleasant, messy, embarrassing, but once you've had it, you're done for life. I should have remembered that there are those rare sufferers who are cursed with recurrence—and it's always worse the second time around.

The weather didn't help. It had rained for four straight days, the sky night-dark when I left my flat in the morning, with no discernible change by the time I returned home at night. I had begun to feel like the little girl in the Ray Bradbury story who lives on a planet where the sun only comes out once in a cycle of years, and then for a brief hour while she's locked in the broom closet. In my case, it was the British Library, not the broom closet, but it came to much the same thing. My raincoat was beginning to attain the dispirited air of an old dog, limp and slightly mangy. We won't even discuss the state of my shoes.

If the research had been going well, perhaps none of this would have mattered. I could forge boldly through the dripping umbrella spokes outside the British Library, sit obliviously in the steamy confines of the tube, and endure with equanimity the ruin of my raincoat. But today I had come to the end of the Letty Alsworthy papers—at least, all the Letty Alsworthy papers the British Library would acknowledge owning—and I was no closer than I had been before to discovering the machinations of the Black Tulip in Ireland. Geoff and Letty's marital difficulties might be interesting reading, but their romantic peccadilloes did not a dissertation chapter make. I could just see the expressions of polite skepticism on the faces of the scholars assembled for the North American Conference on British Studies as I delivered my paper on "The Lives and Loves of the Associates of the Purple Gentian." They'd be dropping off in droves. And, incidentally, so would my grant money.

At that point, I was so low that I couldn't muster more than a feeble flicker of alarm at the thought.

If I were being fair, it wasn't really that bleak. I might have run to the end of the Alsworthy papers, but I did have a hunch as to where to look next—a hunch that didn't involve calling on either Colin or his aunt. Letty had written her parents, claiming to be on a wedding trip with her husband, but another letter, the very last in the collection, told a different story entirely. In the last two of her letters, addressed to her father immediately after her marriage, Letty had confided that she had followed her disappearing husband to Ireland. She urged her father to tell her mother that she had accompanied Lord Pinchingdale on a honeymoon trip, in the hopes that her mother would then blithely spread the misinformation around town. She was traveling, she informed her father, as a widow, under the name of Alsdale, and any urgent matters should be addressed to her in Dublin under that name.

I had to admire her nerve. It was beyond gutsy of her to pick up and go after her errant husband like that. Raw indignation had seethed through every line of that last letter, from her terse account of her husband's departure to the punctures in the paper where she had dotted her I's with piercing precision. Would I have had that sort of nerve in a similar situation? Probably not, when I couldn't even bring myself to call Colin. I would have sat alone at home and called it pride—much as I was doing now.

Tomorrow, I promised myself, dodging around a crowd of teenagers, I would type "Alsdale" into the computers at the British Library and see what came up. With any luck, there might be something from Letty's sojourn in Ireland, something I could use to track the movements of Jane and Geoff without having to resort to the Selwicks. And if my search for the apocryphal Mrs. Alsdale yielded nothing…Well, I'd have to think of something else. Maybe even a trip to the archives in Dublin, in the hopes that something might turn up there. But I would not, not, not call Colin. I thought about it and added another "not," just in case the previous three had seemed insufficiently resolute. He had made it quite clear that he didn't want to speak to me, and if he didn't want to speak to me, I didn't want to speak to him. So there.

Ducking around the big Christmas tree that was already up in the middle of the mall, I skirted the booth selling sheepskin slippers and made straight for the Marks & Spencer at the far end of the mall. Above me, the PA system was already blasting out Christmas music, and the front display of Whittard's tea shop boasted a wide array of winter-themed items, from little mulling packets for wine to tins of cocoa decorated with stylized snowflakes and happy skaters. The front of Marks & Spencer was piled high with tinned plum pudding and dispirited-looking miniature fir trees in gold foil–covered pots. If they looked brown around the edges now, I couldn't imagine how they would survive till December, much less Christmas. It was only mid-November now, hardly late enough in the season to start buying Christmas trees.

At home, it would be nearly Thanksgiving.

Pammy would be having a Thanksgiving dinner for expats and assorted hangers-on at her mother's house in South Kensington next week, but it just wasn't the same. There wouldn't be my little sister dangling bits of Aunt Ally's organic pumpkin bread to the dog under the table, or any of the hundreds of other unspoken traditions that made Thanksgiving more than just another dinner party. Picking up a black plastic shopping basket from the pile in the front of the store, I wandered dispiritedly past the rows of preprepared sandwiches, unable to get excited about the wonders of egg and cress or chicken and stuffing, all in triangular little packages. It wasn't the right kind of stuffing. Stuffing wasn't supposed to be crammed into sandwiches and sold in plastic wedges. Stuffing wasn't stuffing without gobs of turkey fat clinging to the mushrooms and a large, bickering family digging into the gooey mess, scattering bits of corn bread across the tablecloth. Here, they ate stuffing in sandwiches and turkey for Christmas.

I was sick of here.

Everything that had seemed quaint when I first arrived in London had become alien and irritating. Those tiny little bottles of shampoo that cost as much as a full-sized one back home. The way the coffee shops all inexplicably closed by eight. The strange way street names had of changing halfway down a block. The fact that I couldn't get a tub of American peanut butter and no one seemed to sell skirt hangers. I wanted to go home. I missed my little apartment in Cambridge where the sink leaked and the closet door wouldn't close. I missed the rutted brick streets of Harvard Square, where my heels stuck between the stones and my boots slid out from under me in slushy weather. I missed the musty, charred smell of Peet's Coffee that clung to my hair and wouldn't wash out of my sweaters. The thought of the microfilm readers at Widener made me weak with nostalgic sorrow.

With my plastic basket hanging from the crook of my arm, I stared through blurry eyes at the array of preprepared foods. Instead of Lancashire hotpot and chicken tikka masala, I saw the weeks spreading out before me in an endless row of fruitless research and dinners for one. Same old library, same old dinners, same old rainy gray sky. Tomorrow and tomorrow and tomorrow, world without end, amen, with only the occasional outing with Pammy to enliven the gloom, and no chance of home till Christmas.

Only the buzz of the phone in my pocket stopped me from dropping my head into the frozen foods section and bawling.

Resting the edge of my basket on the shelf, I dug into the pocket of my quilted jacket, where I had stuck the phone for easy access during my incessant phone-checking stage. It would probably be Pammy again, I thought listlessly, tugging the phone clear of a fold in the lining. If it was, I'd have to hit ignore and pretend to have left my phone at home. I'd been avoiding Pammy, who tended to regard relations with men as though she were Napoleon and they an opposing army. She mustered her artillery, chose her position, and attacked. Over the past week, we had proceeded from "I don't see why you don't just call him already," to "You could find out where he lives and just buzz and see if he's home," to "If you're not going to call him, I will."

"No, you won't," I informed the buzzing phone.

Only, it wasn't Pammy's number on the screen. In my confusion, my grip loosened, and I had to do a little juggling act with the phone to keep it from plummeting into a pile of prawn sandwiches. It wasn't a London number at all, which ruled out Pammy, nor was it an American number, which ruled out my parents, my siblings, college roommates, and, of course, Grandma.

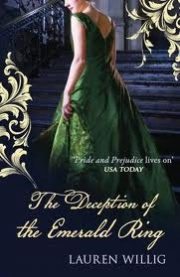

"The Deception of the Emerald Ring" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Deception of the Emerald Ring". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Deception of the Emerald Ring" друзьям в соцсетях.