“Meant it for the best, Pel,” said Sir Roland placatingly. “Meant it for the best! Must be any number of queer people in town—know there are—Club’s full of them.”

“But they ain’t friends of mine!” replied the Viscount. “You can’t go round the club asking a lot of queer-looking strangers to come to Vauxhall with you. Besides, what should we do with them when we got ’em there?”

“Give them supper,” said Sir Roland. “While they have supper we slip off—get the brooch—come back—ten to one no one notices.”

“Well, I won’t do it!” said the Viscount flatly. “We’ll have to think of some way to keep Rule off.”

Ten minutes later Captain Heron walked in to find both gentlemen plunged in profound thought, the Viscount propping his chin in his hands, Sir Roland sucking the head of his cane. Captain Heron looked from one to the other, and said: “I came to see what you mean to do next. You’ve heard nothing of Lethbridge, I suppose?”

The Viscount lifted his head. “By God, I have it!” he exclaimed. “You shall draw Rule off!”

“I shall do what?” asked Captain Heron, startled.

“I don’t see how,” objected Sir Roland.

“Lord, Pom, nothing easier! Private affairs to discuss. Rule can’t refuse.”

Captain Heron laid his hat and gloves down on the table. “Pelham, do you mind explaining? Why has Rule to be drawn off?”

“Why, because of—oh, you don’t know, do you? You see, Horry’s had a letter from someone offering to give her back the brooch if she’ll meet him in the temple at the end of the Long Walk at Vauxhall tonight. Looks like Lethbridge to me—must be Lethbridge. Well, I had it all fixed that she and I and Pom here and you should go to Vauxhall, and while she went to the temple we’d stand guard.”

“That seems a good idea,” nodded Captain Heron. “But it’s surely odd of—”

“Of course it’s a good plan! It’s a devilish good plan. But what must that plaguy fellow Rule do but take it into his head to come too! As soon as I heard that I sent Pom off to invite him to a card-party at his house.”

Sir Roland sighed. “Pressed him as much as I could. No use. Bent on going to Vauxhall.”

“But how the deuce am I to stop him?” asked Captain Heron.

“You’re the very man!” said the Viscount. “All you have to do is to go off to Grosvenor Square now and tell Rule you’ve matters of importance to discuss with him. If he asks you to discuss ’em at once, you say you can’t. Business to attend to. Only time you can spare is this evening. That’s reasonable enough: Rule knows you’re only in town for a day or two. Burn it, he can’t refuse!”

“Yes, but, Pelham, I haven’t anything of importance to discuss with him!” protested Captain Heron.

“Lord, you can think of something, can’t you?” said the Viscount. “It don’t signify what you talk about as long as you keep him away from Vauxhall. Family affairs—money—anything!”

“I’m damned if I will!” said Captain Heron. “After all Rule’s done for me I can’t and I won’t tell him that I want to talk about money!”

“Well, don’t tell him so. Just say you must have a private word with him tonight. He ain’t the man to ask you what it’s about, and dash it, Edward, you must be able to talk about something when it comes to the point!”

“Of course you must,” corroborated Sir Roland. “Nothing simpler. You’ve been at this War in America, haven’t you? Well, tell him about that. Tell him about that battle you was in—forgotten its name.”

“But I can’t beg Rule to give me an evening alone with him, and then sit telling him stories he don’t want to hear about the war!”

“I wouldn’t say that,” temporized Sir Roland. “You don’t know he doesn’t want to hear them. Any number of people take a deal of interest in this war. I don’t myself, but that ain’t to say Rule doesn’t.”

“You don’t seem to understand,” said Captain Heron wearily. “You expect me to make Rule believe I’ve urgent business to discuss with him—”

The Viscount interposed. “It’s you who don’t understand,” he said. “All we care about is keeping Rule away from Vauxhall tonight. If we don’t do it the game’s up. It don’t matter a ha’porth how you keep him away so long as you do keep him away.”

Captain Heron hesitated. “I know that. I’d do it if only I could think of anything reasonable to discuss with him.”

“You’ll think of it, never fear,” said the Viscount encouragingly. “Why, you’ve got the whole afternoon before you. Now you go round to Grosvenor Square at once, there’s a good fellow.”

“I wish to God I’d put off my visit to town till next week!” groaned Captain Heron, reluctantly picking up his hat again.

The Earl of Rule was just about to go in to luncheon when his second visitor was announced. “Captain Heron?” he said. “Oh, by all means show him in!” He waited, standing before the empty fireplace until the Captain came in. “Well, Heron?” he said, holding out his hand. “You come just in time to bear me company over luncheon.”

Captain Heron blushed in spite of himself. “I’m afraid I can’t stay, sir. I’m due in Whitehall almost immediately. I came—you know my time is limited—I came to ask you whether it would be convenient—in short, whether I might wait on you this evening for—for a talk of a confidential nature.”

The Earl’s amused glance rested on him thoughtfully. “I suppose it must be tonight?” he said.

“Well, sir—if you could arrange—I hardly know how I may manage tomorrow,” said Captain Heron, acutely uncomfortable.

There was a slight pause. “Then naturally I am quite at your service,” replied his lordship.

Chapter Twenty-Two

The Viscount, resplendent in maroon velvet, with a fall of Dresden lace at his throat, and his hair thickly powdered and curled in pigeon’s wings over the ears, came at his sister’s urgent request to dine in Grosvenor Square before taking her on to Vauxhall. His presence protected her from a tête-à-tête and if Rule was minded to ask any more awkward questions he, she considered, was better able to answer them than she was.

The Earl, however, behaved with great consideration and conversed affably on most unexceptionable topics. The only bad moment he gave them was when he promised to follow them to Vauxhall if Captain Heron did not detain him at home too long.

“But we’ve no need to worry over that,” said the Viscount as he got into his coach beside Horatia. “Edward’s pledged himself to keep Rule in check till midnight, and by that time we shall have laid hands on that trumpery brooch of yours at last.”

“It isn’t a trumpery b-brooch!” said Horatia. “It’s an heirloom!”

“It may be an heirloom,” replied the Viscount, “but it’s caused more trouble than any heirloom was ever worth, and I’ve come to hate the very mention of it.”

The coach set them down by the waterside, where the Viscount hired a boat to take them the rest of the way. They had three hours to while away before midnight and neither of them was in the mood for dancing. Sir Roland Pommeroy met them at the entrance to the gardens and was very punctilious in handing Horatia out of the boat on to the landing-stage, warning her against wetting her silk-shod foot on a damp patch, and proffering his arm with a great air. As he escorted her down one of the walks towards the centre of the gardens he begged her not to be nervous. “Assure your la’ship Pel and I shall be on the watch!” he said.

“I’m not n-nervous,” replied Horatia. “I w-want very much to see Lord Lethbridge, for I have a great desire to tell him just what I think of him!” Her dark eyes smouldered. “If it weren’t for the scandal,” she announced, “I d-declare I wish he would abduct me. I should make him sorry he d-dared!”

A glance at her fierce frown almost persuaded Sir Roland that she would.

When they arrived at the pavilion they found that in addition to the dancing and the other amusements provided for the entertainment of the company, an oratorio was being performed in the concert hall. Since neither the Viscount nor his sister wished to dance, Sir Roland suggested that they should sit for a while and listen to this. He himself had no great opinion of music, but the only distraction likely to find favour with the Viscount or Horatia was gaming, and he wisely dissuaded them from entering the card-room, on the score that once they had sat down to pharaoh or loo they would entirely forget the real object of their expedition.

Horatia fell in with this suggestion readily enough: diversions were all alike to her until the ring-brooch was in her possession again. The Viscount said that he supposed it could not be more tedious than walking about the gardens or sitting in one of the boxes with nothing to do but to watch the other people passing by. Accordingly they made their way to the concert hall and went in. A play-bill handed them at the door advertised that the oratorio was Susanna, by Handel, a circumstance that nearly made the Viscount turn back at once. If he had known it was a piece by that fellow Handel, nothing would have induced him to come within earshot of it, much less to have paid half a guinea for a ticket. He had once been obliged by his Mama to accompany her to a performance of Judas Maccabeus. Of course he had not had the remotest notion what it would be like or not even filial duty would have dragged him to it, but he did know now and he was damned if he would stand it a second time.

A dowager in an enormous turban who was seated at the end of the row said “Hush!” in accents so severe that the Viscount subsided meekly into his chair and whispered to Sir Roland: “Must try and get out of this, Pom!” However, even his audacity failed before the ordeal of squeezing past the knees of so many musical devotees again, and after glancing wildly to right and left he resigned himself to slumber. The hardness of his chair and the noise the performers made rendered sleep impossible, and he sat in increasing indignation until at long last the oratorio came to an end.

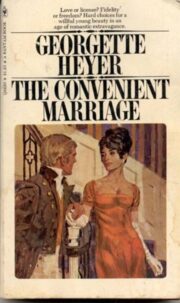

"The Convenient Marriage" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Convenient Marriage". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Convenient Marriage" друзьям в соцсетях.