“Ah, but I beg you will let me show my skill,” said his lordship, removing the patch-box from her hand. He selected a tiny round of black taffeta, and gently turned Horatia’s head towards him. “Which shall it be?” he said. “The Equivocal? I think not. The Gallant? No, not that. It shall be—” He pressed the patch at the corner of her mouth. “The Kissing, Horry!” he said, and bent quickly and kissed her on the lips.

Her hand flew up, touched his cheek, and fell again. Deceitful, odious wretch that she was! She drew back, trying to laugh. “My l-lord, we are not alone! And I—I m-must dress, you know, for I p-promised to g-go with Louisa and Sir Humphrey to the p-play at Drury Lane.”

He straightened. “Shall I send a message to Louisa, or shall I go with you to this play?” he inquired.

“Oh—oh, I m-mustn’t disappoint her, sir!” said Horatia in a hurry. It would never do to be alone with him a whole evening. She might blurt out the whole story, and then—if he believed her—he must think her the most tiresome wife, for ever in a scrape.

“Then we will go together,” said his lordship. “I’ll await you downstairs, my love.”

Twenty minutes later they faced one another across the dining table. “I trust,” said his lordship, carving the duck, “that you were tolerably well amused while I was away, my dear?”

Tolerably well amused? Good heavens! “Oh, yes, sir—t-tolerably well,” replied Horatia politely.

“The Richmond House ball—were you not going to that?”

Horatia gave an involuntary shudder. “Yes, I—went to that.”

“Are you cold, Horry?”

“C-cold? No, sir, n-not at all.”

“I thought you shivered,” said his lordship.

“N-no,” said Horatia. “Oh, no! The—the Richmond House b-ball. It was vastly pretty, with fireworks, you know. Only my shoes p-pinched me, so I d-didn’t enjoy myself m-much. They were new ones, too, with diamonds sewn on them, and I was so c-cross I should have sent them back to the m-makers only they were ruined by the wet.”

“Ruined by the wet?” repeated the Earl.

Horatia’s fork clattered on her plate. That was what came of trying to make conversation! She had known how it would be; of course she would make a slip! “Oh, yes!” she said breathlessly. “I f-forgot to tell you! The b-ball was spoiled by rain. Wasn’t it a pity? I—I got my feet wet.”

“That was certainly a pity,” agreed Rule. “And what did you do yesterday?”

“Yesterday?” said Horatia. “Oh, I—I d-didn’t do anything yesterday.”

There was a laugh in his eyes. “My dear Horry, I never thought to hear such a confession from you,” he said.

“No, I—I did not feel very w-well, so I—I—so I stayed at home.”

“Then I suppose you haven’t yet seen Edward,” remarked the Earl.

Horatia, who was sipping her claret, choked. “Good gracious, yes! Now, however c-could I have come to forget that? Only f-fancy, Rule, Edward is in town!” She was aware that she was sinking deeper into the quagmire, and tried to recover her false step. “B-but how did you know he was here?” she asked.

The Earl waited while the footman removed his plate, and set another in its place. “I have seen him,” he replied.

“Oh—have you? W-where?”

“On Hounslow Heath,” replied the Earl, putting up his glass to survey a pupton of cherries which was being offered to him. “No, I think not... Yes, on Hounslow Heath, Horry. A most unexpected rencontre.”

“It m-must have been. I—I wonder w-what he was doing there?”

“He was holding me up,” said the Earl calmly.

“Oh, w-was he?” Horatia swallowed a cherry stone inadvertently and coughed. “How—how very odd of him!”

“Very imprudent of him,” said the Earl.

“Yes, v-very. P-perhaps he was doing it for a w-wager,” suggested Horatia, mindful of Sir Roland’s words.

“I believe he was.” Across the table the Earl’s eyes met hers. “Pelham and his friend Pommeroy were also of the party. I fear I was not the victim they expected.”

“W-weren’t you? No, of c-course you weren’t! I mean—d-don’t you think it is t-time we started for the p-play, sir?”

Rule got up. “Certainly, my dear.” He picked up her taffeta cloak and put it round her shoulders. “May I be permitted to venture a suggestion?” he said gently.

She glanced nervously at him. “Why, y-yes, sir! What is it?”

“You should not wear rubies with that particular shade of satin, my dear. The pearl set would better become it.”

There was an awful silence; Horatia’s throat felt parched suddenly; her heart was thumping violently. “It—it is too l-late to change them n-now!” she managed to say.

“Very well,” Rule said, and opened the door for her to pass out.

All the way to Drury Lane, Horatia kept up a flow of conversation. What she found to talk about she could never afterwards remember, but talk she did, until the coach drew up at the theatre, and she was safe from a tête-à-tête for three hours.

Coming home there was of course the play to be discussed, and the acting, and Lady Louisa’s new gown, and these topics left no room for more dangerous ones. Pleading fatigue, Horatia went early to bed, and lay for a long time wondering what Pelham had done, and what she should do if Pelham had failed.

She awoke next morning heavy-eyed and despondent. Her chocolate was brought in on a tray with her letters. She sipped it, and with her free hand turned over the billets in the hope of seeing the Viscount’s sprawling handwriting. But there was no letter from him, only a sheaf of invitations and bills.

Setting down her cup she began to open these missives. Yes, just as she had thought. A rout-party; a card-party; she did not care if she never touched a card again; a picnic to Boxhill: never! of course it would rain; a concert at Ranelagh: well, she only hoped she would never be obliged to go to that odious place any more!... Good God, could one have spent three hundred and seventy-five guineas at a mantua-maker’s? And what was this? Five plumes at fifty louis apiece! Well, that was really too provoking, when they had been bought for that abominable Quesaco coiffure which had not become her at all.

She broke the seal of another letter, and spread open the single sheet of plain, gilt-edged paper. The words, clearly written in a copper-plate hand, fairly jumped at her.

If the Lady who lost a ring-brooch of pearls and diamonds in Half-Moon Street on the night of the Richmond House Ball will come alone to the Grecian Temple at the end of the Long Walk at Vauxhall Gardens at Midnight precisely on the twenty-eighth day of September, the brooch shall be restored to her by the Person in whose possession it now is.

There was no direction, no signature; the handwriting was obviously disguised. Horatia stared at it for one incredulous minute and then, with a smothered shriek, thrust her chocolate tray into the abigail’s hands and cast off the bed-clothes. “Quick, I m-must get up at once!” she said. “Lay me out a w-walking dress, and a hat, and my g-gloves! Oh, and run d-downstairs and tell someone to order the l-landaulet—no, not the l-landaulet! my town-coach, to c-come round in half an hour. And take all these l-letters away, and oh, d-do please hurry!”

For once she wasted no time over her toilet, and half an hour later ran down the stairs, her sunshade caught under her arm, her gloves only half on. There was no sign of Rule, and after casting a wary glance in the direction of the library door, she sped past it and was out in the street before anyone could have time to observe her flight.

The coach was waiting, and directing the coachman to drive to Lord Winwood’s lodging in Pall Mall, Horatia climbed in and sank back against the cushions with a sigh of relief at having succeeded in leaving the house without encountering Rule.

The Viscount was at breakfast when his sister was announced, and looked up with a frown. “Lord, Horry, what the devil brings you at this hour? You shouldn’t have come; if Rule knows you’ve dashed off at daybreak it’s enough to make him suspect something’s amiss.”

Horatia thrust a trembling hand into her reticule and extracted a crumpled sheet of gilt-edged paper. “Th-that’s what brings me!” she said. “Read it!”

The Viscount took the letter and smoothed it out. “Well, sit down, there’s a good girl. Have some breakfast... Here, what’s this?”

“P-Pel, can it be L-Lethbridge?” she asked.

The Viscount turned the letter over, as though seeking enlightenment on the back of it. “Dashed if I know!” he said. “Looks to me like a trap.”

“B-but why should it be? Do you think p-perhaps he is sorry?”

“No, I don’t,” said his lordship frankly. “I’d say at a guess that the fellow’s trying to get his hands on you. End of the Long Walk? Ay, I know that Temple. Devilish draughty it is, too. And it’s near one of the gates. Tell you what, Horry: I’ll lay you a pony he means to abduct you.”

Horatia clasped her hands. “But, P-Pel, I must go! I must try and g-get the brooch b-back!”

“So you shall,” said the Viscount briskly. “We’ll see some sport now!” He gave back the letter and took a long drink of ale. “Now you listen to me, Horry. We’ll all go to Vauxhall tonight—you and I and Pom, and Edward too if he likes. At midnight you’ll go to that temple, and the rest of us will lie hid in the shrubbery there. We shall see who goes in, never fear. If it’s Lethbridge, we’ve got him. If it’s another—though, mind you, it looks to me like Lethbridge—you’ve only to give a squawk and we’ll hear you. We shall have that damned brooch by tomorrow, Horry!”

Horatia nodded. “Yes, that’s a very clever plan, P-Pel. And I’ll tell Rule that I am g-going with you, and he w-won’t mind that at all. D-didn’t Lethbridge c-come to town yesterday?”

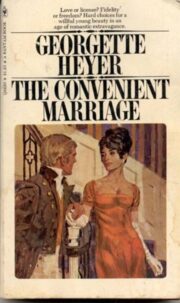

"The Convenient Marriage" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Convenient Marriage". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Convenient Marriage" друзьям в соцсетях.