When the news of his grand perfidy comes out he blames it all on his ambassador, and on letters going astray. It is a slight excuse, but I do not complain. My father will join us as soon as it looks as if we will win. The main thing for me now is that Henry should have his campaign in France and leave me alone to settle with the Scots.

“He has to learn how to lead men into battle,” Thomas Howard says to me. “Not boys into a bawdy house—excuse me, Your Grace.”

“I know,” I reply. “He has to win his spurs. But there is such a risk.”

The old soldier puts his hand over mine. “Very few kings die in battle,” he says. “Don’t think of King Richard, for he all but ran on the swords. He knew he was betrayed. Mostly, kings get ransomed. It’s not one half of the risk that you will be facing if you equip an army and send it across the narrow seas to France, and then try and fight the Scots with what is left.”

I am silent for a moment. I did not know that he had seen what I plan. “Who thinks that this is what I am doing?”

“Only me.”

“Have you told anyone?”

“No,” he says stoically. “My first duty is to England, and I think you are right. We have to finish with the Scots once and for all, and it had better be done when the king is safely overseas.”

“I see you don’t fear overmuch for my safety?” I observe.

He shrugs and smiles. “You are a queen,” he says. “Dearly beloved, perhaps. But we can always get another queen. We have no other Tudor king.”

“I know,” I say. It is a truth as clear as water. I can be replaced but Henry cannot. Not until I have a Tudor son.

Thomas Howard has guessed my plan. I have no doubt in my mind where my truest duty lies. It is as Arthur taught me—the greatest danger to the safety of England comes from the north, from the Scots, and so it is to the north that I should march. Henry should be encouraged to put on his most handsome armor to go with his most agreeable friends in a sort of grand joust against the French. But there will be bloody work on the northern border; a victory there will keep us safe for generations. If I want to make England safe for me and for my unborn son, and for the kings who come after me, I must defeat the Scots.

Even if I never have a son, even if I never have cause to go to Walsingham to thank Our Lady for the son she has given me, I shall still have done my first and greatest duty by this, my beloved country of England, if I beat the Scots. Even if I die in doing it.

I maintain Henry’s resolve; I do not allow him to lose his temper or his will. I fight the Privy Council who choose to see my father’s unreliability as another sign that we should not go to war. Partly, I agree with them. I think we have no real cause against France and no great gains to make. But I know that Henry is wild to go to war and he thinks that France is his enemy and King Louis his rival. I want Henry out of the way this summer, when it is my intention to destroy the Scots. I know that the only thing that can divert him will be a glorious war. I want war, not because I am angry with the French or want to show our strength to my father; I want war because we have the French to the south and the Scots to the north and we will have to engage with one and play with the other to keep England safe.

I spend hours on my knees in the royal chapel; but it is Arthur that I am talking to, in long, silent reveries. “I am sure I am right, my love,” I whisper into my clasped hands. “I am sure that you were right when you warned me of the danger of the Scots. We have to subdue the Scots, or we will never have a kingdom that can sleep in peace. If I can have my way, this will be the year when the fate of England is decided. If I have my way, I will send Henry against the French and I will go against the Scots and our fate can be decided. I know the Scots are the greater danger. Everyone thinks of the French—your brother thinks of nothing but the French—but these are men who know nothing of the reality of war. The enemy who is across the sea, however much you hate him, is a lesser enemy than the one who can march over your borders in a night.”

I can almost see him in the shadowy darkness behind my closed eyes. “Oh, yes,” I say with a smile to him. “You can think that a woman cannot lead an army. You can think that a woman cannot wear armor. But I know more about warfare than most men at this peaceable court. This is a court devoted to jousting; all the young men think war is a game. But I know what war is. I have seen it. This is the year when you will see me ride out as my mother did, when you see me face our enemy—the only enemy that really matters. This is my country now; you yourself made it my country. And I will defend it for you, for me, and for our heirs.”

The English preparations for the war against France went on briskly, with Katherine and Thomas Wolsey, her faithful assistant, working daily on the muster rolls for the towns, the gathering of provisions for the army, the forging of armor, and the training of volunteers to march, prepare to attack, and retreat, on command. Wolsey observed that the queen had two muster rolls, almost as if she were preparing for two armies. “Are you thinking we will have to fight the Scots as well as the French?” he asked her.

“I am sure of it.”

“The Scots will snap at us as soon as our troops leave for France,” he said. “We shall have to reinforce the borders.”

“I hope to do more than that,” was all she said.

“His Grace the King will not be distracted from his war with France,” he pointed out.

She did not confide in him, as he wanted her to do. “I know. We must make sure he has a great force to take to Calais. He must not be distracted by anything.”

“We will have to keep some men back to defend against the Scots. They are certain to attack,” he warned her.

“Border guards,” she said dismissively.

Handsome young Edward Howard, in a new cloak of dark sea-blue, came to take leave of Katherine as the fleet prepared to set sail with orders to blockade the French in port, or engage them if possible on the high seas.

“God bless you,” said the queen, and heard her voice a little shaken with emotion. “God bless you, Edward Howard, and may your luck go with you as it always does.”

He bowed low. “I have the luck of a man favored by a great queen who serves a great country,” he said. “It is an honor to serve my country, the king…and”—he lowered his voice to an intimate whisper—“and you, my queen.”

Katherine smiled. All of Henry’s friends shared a tendency to think themselves into the pages of a romance. Camelot was never very far away from their minds. Katherine had served as the lady of the courtly myth ever since she had been queen. She liked Edward Howard more than any of the other young men. His genuine gaiety and his open affection endeared him to everyone, and he had a passion for the navy and the ships under his command that commended him to Katherine, who saw the safety of England could only be assured by holding the seas.

“You are my knight, and I trust you to bring glory to your name and to mine,” she said to him, and saw the gleam of pleasure in his eyes as he dropped his dark head to kiss her hand.

“I shall bring you home some French ships,” he promised her. “I have brought you Scots pirates, now you shall have French galleons.”

“I have need of them,” she said earnestly.

“You shall have them if I die in the attempt.”

She held up a finger. “No dying,” she warned him. “I have need of you, too.” She gave him her other hand. “I shall think of you every day and in my prayers,” she promised him.

He rose up and with a swirl of his new cloak he went out.

It is the feast of St. George and we are still waiting for news from the English fleet, when a messenger comes in, his face grave. Henry is at my side as the young man tells us, at last, of the sea battle that Edward was so certain he should win, that we were so certain would prove the power of our ships over the French. With his father at my side, I learn the fate of Edward, my knight Edward, who had been so sure that he would bring home a French galleon to the Pool of London.

He pinned down the French fleet in Brest and they did not dare to come out. He was too impatient to wait for them to make the next move, too young to play a long game. He was a fool, a sweet fool, like half the court, certain that they are invincible. He went into battle like a boy who has no fear of death, who has no knowledge of death, who has not even the sense to fear his own death. Like the Spanish grandees of my childhood, he thought that fear was an illness he could never catch. He thought that God favored him above all others and nothing could touch him.

With the English fleet unable to go forwards and the French sitting snug in harbor, he took a handful of rowing boats and threw them in, under the French guns. It was a waste, a wicked waste of his men and of himself—and only because he was too impatient to wait and too young to think. I am sorry that we sent him, dearest Edward, dearest young fool, to his own death. But then I remember that my husband is no older and certainly no wiser and has even less knowledge of the world of war, and that even I, a woman of twenty-seven years old, married to a boy who has just reached his majority, can make the mistake of thinking that I cannot fail.

Edward himself led the boarding party onto the flagship of the French admiral—an act of extraordinary daring—and almost at once his men failed him, God forgive them, and called him away when the battle was too hot for them. They jumped down from the deck of the French ship into their own rowing boats, some of them leaping into the sea in their terror to be away, shot ringing around them like hailstones. They cast off, leaving him fighting like a madman, his back to the mast, hacking around him with his sword, hopelessly outnumbered. He made a dash to the side and if a boat had been there, he might have dropped down to it. But they had gone. He tore the gold whistle of his office from his neck and flung it far out into the sea, so that the French would not have it, and then he turned and fought them again. He went down, still fighting; a dozen swords stabbed him. He was still fighting as he slipped and fell, supporting himself with one arm, his sword still parrying. Then, a hungry blade slashed at his sword arm, and he was fighting no more. They could have stepped back and honored his courage, but they did not. They pressed him further and fell on him like hungry dogs on a skin in Smithfield market. He died with a hundred stab wounds.

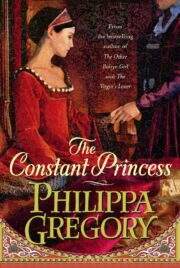

"The Constant Princess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Constant Princess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Constant Princess" друзьям в соцсетях.