Stockmar arrived at Kensington Palace to be warmly welcomed by Victoria because he brought letters and messages from Uncle Leopold and in these letters she read that she must love and trust Stockmar for Leopold’s sake.

This she was very ready to do. She had a new idol; she listened to everything he said; she was certain of his wisdom. If he was not Uncle Leopold he was the next best thing.

‘Baron Stockmar,’ she wrote in her Journal, ‘is one of the few people who tell plain, honest truth, don’t flatter and give wholesome and necessary advice, and strive to do good and smooth all dissensions. He is Uncle Leopold’s greatest and most confidential attaché and disinterested friend, and I hope he is the same to me, at least I feel so towards him.’

When she had written that she thought of Lehzen who would read her Journal and think of all the years that they had been together. She wanted Lehzen to know that there would never be another friend for her like her dear Baroness so she added: ‘Lehzen being of course the greatest friend I have.’

Stockmar was delighted with his pupil. Her frank acceptance of him, her innocent belief in him because Uncle Leopold had sent him, and afterwards because she sensed his great qualities, pleased him.

He wrote back to Leopold of his enthusiasm for her. She was bright and intelligent. She was above all aware of her inexperience and eager to learn.

‘England will grow great and famous under her rule,’ prophesied Stockmar.

So during those weeks which she felt to be so momentous Victoria was relieved to have Baron Stockmar close at hand.

At last came that Wednesday in May of the year 1837 which was Victoria’s eighteenth birthday.‘How old!’ she wrote in her Journal. ‘And yet I am far from being what I should be. I shall from this day take the firm resolution to study with renewed assiduity to keep my attention always fixed on whatever I am about and to strive to become every day less trifling and more fit for what, if Heaven wills, I’m some day to be.’

It was a solemn time, waking in the familiar bedroom and thinking: I am now of age. I am no longer a child. Everything will be different from now on.

But first there was a birthday – the most important of them all – to be celebrated. To her delight she suddenly heard the sound of singing beneath her window; and she recognised the voice of George Rodwell, the Musical director of Covent Garden, who had composed a special piece of music for her birthday. She leaned out of the window and clapped her applause.

Lehzen said it was a very pleasant compliment and it was time she dressed.

The presents were laid out on her table and she eagerly examined them and thanked everyone; and the gift which delighted her most perhaps, because it showed that however angry the King might be with her mother he had an affection for her, was the beautiful grand piano which was delivered with His Majesty’s affection and best wishes.

‘Oh, it is beautiful … beautiful!’ she cried; while the Duchess looked at the piano as though it were some loathsome monster.

But Victoria thought: She cannot forbid me to accept it or to play it. She cannot forbid me to do anything now!

It was an intoxicating thought. Freedom! There was no gift quite as desirable as that.

She was realising how important she was. The heiress to the throne and of age!

During the morning the City of London sent a deputation to congratulate the Princess on coming of age. Victoria received it with her mother standing by her side and when she was about to thank them, the Duchess laid a restraining hand on her arm and herself addressed them.

She told them that she, a woman without a husband, had brought up her daughter single-handed and she had never once swerved from her duty nor forgotten the great destiny which awaited the Princess. When her husband had died she had been left alone, not speaking the language, almost penniless with such a great task ahead of her. This she had not shirked …

Oh, Mamma, Victoria wanted to scream. Be silent.

In the afternoon Victoria and the Duchess, with Lehzen, drove through the streets and everywhere the flags were flying in her honour. The day had been declared a public holiday and people thronged the streets, and when her carriage passed a great cheer went up.

And later she went to St James’s for the state ball. She was terrified of how the King would behave towards her mother and she towards him; but in her heart she believed that now that she was of age everything was going to be different.

She was very sorry to learn that the King was unable to attend because he was so ill; and that the Queen was not well enough to come either. Her aunt, the Princess Augusta, received them and she consoled herself that at least there would be no unpleasantness.

She could give herself up to the pleasures of the ball. How delightful to dance to heavenly music. The first dance was with the Duke of Norfolk’s grandson and he danced with great skill and told her she looked beautiful.

There were many other dances and it was a wonderful ball; and when she entered her carriage to return to Kensington the people had come into the courtyard to cheer her.

A wonderful birthday, an amusing ball, but she knew it was more than that. It was the beginning of a new life.

Chapter XXIII

HER MAJESTY

Lord Conyngham, the Lord Chamberlain, called at Kensington Palace to be received by Sir John Conroy.

‘I have,’ said Lord Conyngham, ‘a letter here from His Majesty to the Princess Victoria.’

Sir John held out his hand for it. There had been no reply from the letter the Duchess had sent to Lord Melbourne and he believed that it had come to the Prime Minister’s ears that the Duchess had not spoken to Victoria about an extended Regency, in which case the Prime Minister would tactfully pretend that he never received such a letter.

But a message from the King to the Princess must of course be seen first by Sir John and the Duchess.

Lord Conyngham, however, did not pass over the letter. Instead he said: ‘I have His Majesty’s instructions to put this letter into no hands but those of the Princess Victoria.’

Sir John sent one of the pages to tell the Duchess that the King’s Chamberlain was at the Palace with a message from the King.

The Duchess swept in, greeted Conyngham haughtily and held out her hand for the letter.

‘I am sorry, Your Grace, but the King’s instructions are that his letter is to be given to none but the Princess.’

The Duchess flushed angrily but could do nothing but send a message to Lehzen to bring the Princess Victoria to her drawing-room without delay.

When Victoria arrived Lord Conyngham bowed and handed her the letter.

‘It is from His Majesty, Your Highness.’

Victoria took it.

‘Are you not going to open it?’ asked the Duchess, coming to stand beside her and obviously using great restraint in not snatching the letter from her daughter.

‘I think’ said Victoria, ‘that I would prefer to read it in my own sitting-room … by myself.’

The Duchess was affronted. The Princess Victoria had never been allowed to be alone even and now she was proposing to read an important letter without sharing it with her mother.

There was a new dignity about the Princess, an assurance; she had crossed the bridge between restraint and freedom and she was safely on the other side.

She took the letter, she read it. The King wrote affectionately that now she was of age she might wish to have a separate establishment from her mother’s and he was prepared to allow her ten thousand a year of her own.

Gleefully Victoria accepted.

Life was changing rapidly. She was becoming independent. Not that her mother would allow that without a fight; and the King was growing so ill that nothing was done immediately about her separate establishment. The Duchess wrote to the Prime Minister to the effect that ten thousand a year was too much for Victoria and she thought she should have a share of it.

But everything else was set temporarily aside because the King’s condition was so rapidly deteriorating. It was clear that he could not live long; he had lost the use of his legs and had to be wheeled wherever he went. The FitzClarence children were at Windsor, all rancour forgotten. George, Earl of Munster, had given up quarrelling with his father; his daughter Mary was constantly with him; and Augustus read the prayers every morning; but it was Adelaide who was constantly at his side and if she were not in the room he became uneasy.

He knew he was dying. It was as though he had made up his mind that he would live until Victoria was of age. Now that day had come; he had had his revenge on the Duchess and would depart in peace.

‘Any day now, it will be the end,’ said the courtiers, the ministers and the people in the streets.

But the King lingered on.

The Duke of Cumberland could not give up hope. He was excited. Surely his moment had come. The King was dying and the heiress to the throne was a girl of eighteen. Something must be done.

Surely the people would rather have a strong man at the head of affairs.

Frederica, grown philosophical, said: ‘You’re crazy, Ernest. The people want Victoria. A young girl like that … providing she’s got the ministers behind her can bring back respect to the Monarchy. I hear William said that sailors and soldiers will enjoy having a girl-Queen to fight for. It’s true, Ernest. Why can’t you be content? The day William dies you’ll be the King of Hanover.’

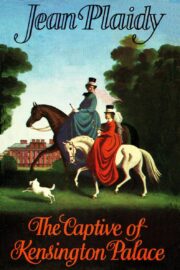

"The Captive of Kensington Palace" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Captive of Kensington Palace". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Captive of Kensington Palace" друзьям в соцсетях.