But she said nothing.

Later that day Lady de l’Isle died.

‘Certainly,’ said the Duchess, ‘I shall not cancel my dinner party. What have this woman’s affairs to do with me?’

Victoria took her usual refuge in tears. She had had Lady de l’Isle’s children in her rooms and tried to amuse them with her sketches to take their minds off what was happening.

Oh dear, she thought, Mamma cannot give a dinner party while the King’s daughter lies dead in the Palace. But apparently she could.

The King was demented.

‘My little Sophie! But what were those doctors doing? She was well enough during her pregnancy. My Sophie! Why her mother had ten children and there was never any trouble.’

He wept and there was no comforting him. He told everyone how Sophie had been born and how he had loved her. She was his eldest daughter and had been the most enchanting of little girls. He and Dorothy had been so proud of her. No, this was too cruel. He couldn’t bear it.

Melbourne thought he was going mad and wondered how he was going to control a young Queen who was not yet of age. But she would be in a few weeks’ time. He had received a letter from her mother in which she stated that Victoria wished for an extended Regency. He could scarcely approach the King on this matter yet. So the Princess felt herself inadequate to rule without her mother!

‘God help us!’ groaned Melbourne. ‘How shall we work with the Duchess of Kent!’ A young girl would be easier to advise and control and from what he had seen of Victoria he believed her to be intelligent, by which he meant that she would be wise enough to realise her lack of experience and listen to her Prime Minister. But the mother!

He would shelve the letter for a while, at least until the Queen came home. What ill luck that she should be abroad at this time when the King needed her. If she did not come home soon his sanity would desert him. Only those who lived close to William knew how much he depended on Adelaide.

He sent a despatch to the Queen urging her to return to England.

Adelaide’s mother had meanwhile died and she came home with all speed.

‘Oh, Adelaide, how glad I am! How I missed you! And this terrible terrible news about Sophie. Who would have thought it possible?’

‘Dear William, it is heart-breaking. And the children?’

‘They are still at Kensington. Young Victoria is being very good to them and they seem to be fond of her. They say they are happier with her than they would be anywhere else.’

‘Dear Victoria. She is so good. And it’s true. She will be gay with them and gaiety is what they want, poor mites.’

The King nodded. ‘My little Sophie, Adelaide … my eldest … I’ll never forget the day she was born.’

Adelaide soothed and comforted and the King’s health recovered a little. His ministers noticed and were relieved.

Adelaide, however, was really ill. Her cough had become much worse and the journey to Saxe-Meiningen on such a dismal mission had sapped her strength.

She must rest, the doctors told her. She must take great care of her health and remember how important she was to the King.

The Princess Augusta was at Windsor and she assured Adelaide that she could take over many of her duties. Adelaide’s chief one at the moment, as the doctors had told her, was to get well.

‘You see what happens to William when you’re not there, Adelaide,’ Augusta reminded her. ‘For Heaven’s sake, guard your health. William needs you.’

‘There is the Drawing-Room …’

‘But think what effect Drawing-Rooms have on you. I know you have to bandage your knees to help with the swelling.’

‘Oh, Augusta, I feel so foolishly weak and ineffectual.’

‘You are certainly not ineffectual. And if you could know what William is like when you’re away you’d be fully aware of how important you are. No, I will take your place at the Drawing-Room and you will rest.’

Sir John had persuaded the Duchess that she must attend the King’s Drawing-Room. He had expressly said that Victoria must appear at Court and that he was going to insist on her doing so. Therefore to ignore this invitation would infuriate him, and, moreover, they must remember that he was the King and had certain powers.

The Duchess was not averse. She would show them that she cared nothing for the King, that she was fully aware that very soon he would have departed this world and her daughter would be the Queen and herself Regent.

She was taking Sir John with her to let everyone see that she would have whom she chose about her. She was well aware of the King’s dislike of Sir John – he had referred more than once to her evil advisers – but that was of no importance. If she wished Sir John to accompany her he should do so.

Victoria sitting beside her mother in the carriage which was taking them to St James’s for the Drawing-Room was conscious of her mother’s truculent mood.

In a few weeks’ time I shall be eighteen, she kept telling herself. Everything will be different then.

In the Drawing-Room the Princess Augusta, deputy for the Queen, received them; and then the King came in.

The Duchess chuckled inwardly. He looked ill and was quite tottery; it was a long time since she had seen him looking so old.

He was having a word or two with a guest here and there and when he came to the Duchess he looked through her as though she did not exist. It was a deliberate insult and every one was aware of it.

Old fool, thought the Duchess. Much good that will do him. Victoria will soon be Queen and he can’t alter that. The sooner he is in his grave the better for everyone. He looks as if another step or two will take him there.

The King had seen Sir John Conroy. That fellow … among his guests! He had no invitation to appear at his Court. If that woman thought he was going to receive her paramour in his Drawing-Room she was mistaken.

He called: ‘Conyngham! Conyngham!’

The Lord Chamberlain hurried to his side.

The King’s face had grown very red and there was a deep silence throughout the room as William pointed to Sir John Conroy.

‘Turn that fellow out!’ he said. ‘I’ll not have him here.’

There was a gasp of amazement. Everyone was wondering what the King would do next as Sir John Conroy with a shrug of his shoulders and a sneer on his lips was escorted out of the King’s Drawing-Room.

William was telling Adelaide all about the incident in the Drawing-Room. Adelaide, her head aching, her cough worrying her, listened and was relieved at least that she had not been present.

‘These terrible quarrels between you and the Duchess are doing you no good, William,’ she said.

‘You aren’t suggesting I should let her have her own way.’

‘No, but perhaps it would be better to ignore her.’

‘Adelaide, that woman is a fiend. What that child of hers has suffered, I can’t imagine.’

‘Poor Victoria! I don’t think she had much fun as a child.’

‘I’m sure she didn’t. But she’ll be of age next month.’

‘She must have a very special celebration.’

‘The child is very musical. I’ve heard that she likes singing and playing the piano better than anything else. I shall give her a grand piano for her birthday.’

‘Oh, William, that’s a lovely idea.’

‘I knew you’d think so. And there’ll be other things, too. I’ve only got to live a few more weeks, Adelaide, and I’ll have had my wish. One thing I was determined not to do was to die and let that woman have the Regency.’

‘You’re going on living for a long time yet.’

‘Yes, yes,’ said William soothed, but he was not so sure in his heart.

He went on to talk to Adelaide about the Drawing-Room. He believed his feud with That Woman gave him a zest for living.

He had thought of something else. ‘Now that my darling Sophia is dead my daughter Mary shall go to Kensington. She’ll keep an eye on Madam Kent. By God, she’ll be appropriating the entire Palace if we don’t look out. I wonder when she’ll want to move into St James’s and Windsor?’

He was growing excited again and Adelaide talked of the grandchildren to soothe him.

Chapter XXII

AN IMPORTANT WEDNESDAY IN MAY

At the beginning of May the King’s health deteriorated rapidly. At a public luncheon he was seen to be very ill and looked as though he were about to faint. The Queen was at hand and managed to guide him through the meal and afterwards he did actually faint.

‘You must rest from all functions for a few days,’ she told him; and he was feeling so ill that he allowed himself to be persuaded.

The Duchess was delighted when she heard the news. ‘Not long now,’ she told Sir John, but Sir John, still smarting from that public rebuff, was inclined to be morbid. What Victoria would be like when she reached her majority he was not at all sure. There had been so many signs of rebellion lately. They had kept her almost a prisoner for eighteen years but in doing so they had failed to win her confidence. They should have dismissed that doting Lehzen with her stern ideas of duty and her caraway seeds. Victoria clearly regarded her as the one person in the Palace whom she could trust.

Leopold was keeping her in leading strings but they had to stretch too far across the Channel to be as effective as they might have been. Leopold was the first to realise this and as the great moment was coming nearer and nearer he decided to send Baron Stockmar to England to report on the situation there and guide Victoria.

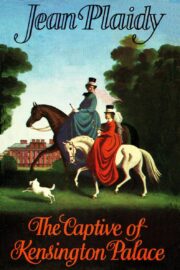

"The Captive of Kensington Palace" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Captive of Kensington Palace". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Captive of Kensington Palace" друзьям в соцсетях.