"Tumble, sir? Why should he do that?"

"He was at pains to explain the reason. It seems he had been commanded to hold the door to prevent my entering-so when I jerked it open, sooner than loose his hold, he fell out on to the road. Of course, I apologised most abjectly-and we had some conversation. Quite a nice little man. . . It made me laugh to see him sprawling on the road, though!"

"Wish I could have seen it, your honour. I would ha' liked fine to ha' been beside ye." He looked down at the lithe form with some pride. "I'd give something to see ye hold up a coach, sir!"

Haresfoot in hand, Jack met his admiring eyes in the glass, and laughed.

"I make no doubt you would. . . . I have cultivated a superb voice, a trifle thick and beery, a little loud, perhaps-ah, something to dream of o' nights! I doubt they do, too," he added reflectively, and affixed the patch at the corner of his mouth.

"So? A little low, you think? But 'twill suffice- What's toward?"

Down below in the street there was a great stirring and bustling: horses' hoofs, shouts from the ostlers, and the sound of wheels on the cobble-stones. Jim went to the window and looked down, craning his neck to see over the balcony.

"'Tis a coach arrived, sir."

"That much had I gathered," replied my lord, busy with the powder.

"Yes, sir. O lord, sir!" He was shaken with laughter.

"What now?"

"'Tis the curiousest sight, sir! Two gentlemen, one fat and t'other small! One's all shrivelled-looking, like a spider, while t'other-"

"Resembles a hippopotamus-particularly in the face?"

"Well yes, sir. He do rather. And he be wearing purple."

"Heavens, yes! Purple, and an orange waistcoat!"

Jim peered afresh.

"So it is, sir! But how did ye know?" Even as he put the question, understanding flashed into Jim's eyes.

"I rather think that I have had the honour of meeting these gentlemen," replied my lord placidly. "My buckle, Jim. . . . Is't a prodigious great coach with wheels picked out in yellow?"

"Ay, your honour. The gentlemen seem a bit put out, too."

"That is quite probable. Does the smaller gentleman wear somewhat-ah-muddied garments?"

"I can't see, sir; he stands behind the fat gentleman."

"Mr. Bumble Bee. . . . Jim!"

"Sir!" Jim turned quickly at the sound of the sharp voice.

He found that my lord had risen, and was holding up a waistcoat of pea-green pattern on a bilious yellow ground, between a disgusted finger and thumb. Before his severe frown Jim dropped his eyes and stood looking for all the world like a schoolboy detected in some crime.

"You put this-this monstrosity-out for me to wear?" in awful tones.

Jim eyed the waistcoat gloomily and nodded.

"Yes, sir."

"Did I not specify cream ground?"

"Yes, sir. I thought-I thought that 'twas cream!"

"My good friend, it is-it is-I cannot say what it is. And pea-green!" he shuddered. "Remove it."

Jim hurried forward and disposed of the offending garment.

"And bring me the broidered satin. Yes, that is it. It is particularly pleasing to the eye."

"Yes, sir," agreed the abashed Jim.

"You are excused this time," added my lord, with a twinkle in his eye. "What are our two friends doing?"

Salter went back to the window

"They've gone into the house, sir. No, here's the spider gentleman! He do seem in a hurry, your honour!"

"Ah!" murmured his lordship. "You may assist me into this coat. Thanks."

With no little difficulty, my lord managed to enter into the fine satin garment, which, when on, seemed moulded to his back, so excellently did it fit. He shook out his ruffles and slipped the emerald ring on to his finger with a slight frown.

"I believe I shall remain here some few days," he remarked presently. "To-ah-allay suspicion." He looked across at his man as he spoke, through his lashes.

It was not in Jim's nature to inquire into his master's affairs, much less to be surprised at anything he might do or say. He was content to receive and promptly execute his orders, and to worship Carstares with a dog-like devotion, following blindly in his wake, happy as long as he might serve him.

Carstares had found him in France, very down upon his luck, having been discharged from the service of his late master owing to the penniless condition of that gentleman's pocket. He had engaged him as his own personal servant, and the man had remained with him ever since, proving an invaluable acquisition to my Lord John. Despite a singularly wooden countenance, he was by no means a fool, and he had helped Carstares out of more than one tight corner during his inglorious and foolhardy career as highwayman. He probably understood his somewhat erratic master better than anyone else, and he now divined what was in his mind. He returned that glance with a significant wink.

"'Twas them gentlemen ye held up to-day, sir?" he asked, jerking an expressive thumb towards the window.

"M'm. Mr. Bumble Bee and friend. It would almost appear so. I think I do not fully appreciate Mr. Bumble Bee. I find his conduct rather tiresome. But it is just possible that he thinks the same of me. I will further my acquaintance with him."

Jim grunted scornfully, and an inquiring eye was cocked at him.

"You do not admire our friend? Pray, do not judge him by his exterior. He may possess a beautiful mind. But I do not think so. N-no, I really do not think so." He chuckled a little. "Do you know, Jim, I believe I am going to enjoy myself to-night!"

"I don't doubt it, your honour. 'Twere child's play to trick the fat gentleman."

"Probably. But it is not with the fat gentleman that I shall have to deal. 'Tis with all the officials of this charming town, an I mistake not. Do I hear the small spider returning?"

Salter stepped back to the window.

"Ay, sir-with three others."

"Pre-cisely. Be so good as to hand me my snuffbox. And my cane. Thank you. I feel the time has now come for me to put in an appearance. Pray, bear in mind that I am new come from France and journey by easy stages to London. And cultivate a stupid expression. Yes, that will do excellently."

Jim grinned delightedly; he had assumed no expression of stupidity, and was consequently much pleased with this pleasantry. He swung open the door with an air, and watched "Sir Anthony" mince along the passage to the stairs.

In the coffee-room the city merchant, Mr. Fudby by name, was relating the story of his wrongs, with many an impressive pause, and much emphasis, to the mayor, town-clerk, and beadle of Lewes. All three had been fetched by Mr. Chilter, his clerk, in obedience to his orders, for the bigger the audience the better pleased was Mr. Fudby. He was now enjoying himself quite considerably, despite the loss of his precious cash-box.

So was not Mr. Hedges, the mayor. He was a fussy little man who suffered from dyspepsia; he was not interested in the affair, and he did not see what was to be done for Mr. Fudby. Further, he had been haled from his dinner, and he was hungry; and, above all, he found Mr. Fudby very unattractive. Still, a highroad robbery was serious matter enough, and some course of action must be thought out; so he listened to the story with an assumption of interest, looking exceedingly wise, and, at the proper moments, uttering sounds betokening concern.

The more he saw and heard of Mr. Fudby, the less he liked him. Neither did the town-clerk care for him. There was that about Mr. Fudby that did not endear him to his fellow-men, especially when they chanced to be his inferiors in the social scale. The beadle did not think much about anything. Having decided (and rightly) that the affair had nothing whatever to do with him, he leaned back in his chair and stared stolidly up at the ceiling.

The tale Mr. Fudby was telling bore surprisingly little resemblance to the truth. It was a much embellished version, in which he himself had behaved with quite remarkable gallantry. It had been gradually concocted during the journey to Lewes.

He was still holding forth when my lord entered the room. Carstares raised his glass languidly to survey the assembled company, bowed slightly, and walked over to the fire. He seated himself in an armchair and took no further notice of anybody.

Mr. Hedges had recognised at a glance that here was some grand seigneur and wished that Mr. Fudby would not speak in so loud a voice. But that individual, delighted at having a new auditor, continued his tale with much relish and in a still louder tone.

My lord yawned delicately and took a pinch of snuff.

"Yes, yes," fussed Mr. Hedges. "But, short of sending to London for the Runners, I do not see what I can do. If I send to London, it must, of course, be at your expense, sir."

Mr. Fudby bristled.

"At my expense, sir? Do ye say at my expense? I am surprised! I repeat-I am surprised!"

"Indeed, sir? I can order the town-crier out, describing the horse, and-er-offering a reward for the capture of any man on such an animal. But-" he shrugged and looked across at the town-clerk-"I do not imagine that 'twould be of much use-eh, Mr. Brand?"

The clerk pursed his lips and spread out his hands.

"I fear not; I very much fear not. I would advise Mr. Fudby to have a proclamation posted up round the country." He sat back with the air of one who has contributed his share to the work, and does not intend to offer any more help.

"Ho!" growled Mr. Fudby. He blew out his cheeks. "'Twill be a grievous expense, though I suppose it must be done, and I cannot but feel that if it had not been for your deplorably cowardly conduct, Chilter-yes, cowardly conduct, I say-I might never have been robbed of my two hundred!" He snuffled a little, and eyed the flushed but silent Chilter with mingled reproach and scorn. "However, my coachman assures me he could swear to the horse again, although he cannot remember much about the man himself. Chilter! How did he describe the horse?"

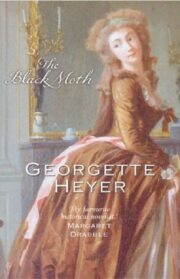

"The Black Moth" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Black Moth". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Black Moth" друзьям в соцсетях.