Up the terrace walls crept roses, yellow and red, pink and white, and tossed their trailing sprays across the parapet. Over the walls of the house they climbed, mingling with purple clematis, jasmine, and sickly honeysuckle. The air was heavy with their united perfumes, while, wafted from a bed below, came the smoky scent of lavender.

The old house seemed half asleep, basking in the sunlight. Save for a peacock preening its feathers on the terrace steps, there was no sign of life. . . .

The old place had harboured generations of Carstares. Earl had succeeded Earl and reigned supreme, and it was only now that there was no Earl living there. No one knew where he was. Scarce a month ago one died, but the eldest son was not there to take his place. For six years he had been absent, and none dared breathe his name, for he disgraced that name, and the old Earl cast him off and forbade all mention of him. But the poor folk of the countryside remembered him. They would tell one another tales of his reckless courage; his sweet smile and his winning ways; his light-heartedness and his never-failing kindness and good-humour. What a rider he was! To see him sit his horse! What a swordsman! Do ye mind the time he fought young Mr. Welsh over yonder in the spinney with half the countryside watching? Ah, he was a one, was Master Jack! Do ye mind how he knocked the sword clean out o' Mr. Welsh's hand, and then stood waiting for him to pick it up? And do ye mind the way his eyes sparkled, and how he laughed, just for the sheer joy o' living?

Endless anecdotes would they tell, and the old gaffers would shake their heads and sigh, and long for the sight of him again. And they would jerk their thumbs towards the Manor and shrug their old shoulders significantly. Who wanted Mr. Richard for squire? Not they, at least. They knew he was a good squire and a kindly man, but give them Master John, who would laugh and crack a joke and never wear the glum looks that Mr. Richard affected.

In the house, Richard Carstares paced to and fro in his library, every now and again pausing to glance wretchedly up at the portrait of his brother hanging over his desk. The artist had managed to catch the expression of those blue eyes, and they smiled down at Richard in just the way that John was always wont to smile-so gaily, and withal so wistfully.

Richard was twenty-nine, but already he looked twice his age. He was very thin, and there were deep lines on his good-looking countenance. His grey eyes bore a haunted, care-worn look, and his mouth, though well-shaped, was curiously lacking in determination. He was dressed soberly, and without that touch of smartness that had characterised him six years ago. He wore black in memory of his father, and it may have been that severity, only relieved by the lace at his throat, that made his face appear so prematurely aged. There was none of his brother's boyishness about him; even his smile seemed forced and tired, and his laughter rarely held merriment. . . .

He pulled out his chronometer, comparing it with the clock on the mantelpiece. His pacing took him to the door, and almost nervously he pulled it open, listening.

No sound came to his ears. Back again, to and fro across the room, eagerly awaiting the clanging of a bell. It did not come, but presently a footfall sounded on the passage without, and someone knocked at the door.

In two strides Richard was by it, and had flung it wide. Warburton stood there.

Richard caught his hand.

"Warburton! At last! I have been waiting this hour and more!"

Mr. Warburton disengaged himself, bowing.

"I regret I was not able to come before, sir," he said primly.

"I make no doubt you travelled back as quickly as possible-come in, sir."

He led the lawyer into the room and shut the door.

"Sit down, Warburton-sit down. You-you found my brother?"

Again Warburton bowed.

"I had the felicity of seeing his lordship, sir."

"He was well? In good spirits? You thought him changed-yes? Aged perhaps, or-"

"His lordship was not greatly changed, sir."

Richard almost stamped in his impatience.

"Come, Warburton, come! Tell me everything. What did he say? Will he take the revenues? Will he-"

"His lordship, sir, was reluctant to take anything, but upon maturer consideration, he-ah-consented to accept his elder son's portion. The revenues of the estate he begs you will make use of."

"Ah! But you told him that I would touch nought belonging to him?"

"I tried to persuade his lordship, sir. To no avail. He desires you to use Wyncham as you will."

"I'll not touch his money!"

Warburton gave the faintest of shrugs.

"That is as you please, sir."

Something in the suave voice made Richard, from his stand by the desk, glance sharply down at the lawyer. Suspicion flashed into his eyes. He seemed about to speak, when Warburton continued:

"I believe I may set your mind at rest on one score, Mr. Carstares: his lordship's situation is tolerably comfortable. He has ample means."

"But-but he lives by-robbery!"

Warburton's thin lips curled a little.

"Does he not?" persisted Carstares.

"So he would have us believe, sir."

"'Tis true! He-waylaid me!"

"And robbed you, sir?"

"Rob me? He could not rob his own brother Warburton!"

"Your pardon, Mr. Carstares-you are right: his lordship could not rob a brother. Yet have I known a man do such a thing."

For a long minute there was no word spoken. The suspicion that had dwelt latent in Carstares' eyes, sprang up again. Some of the colour drained from his cheeks, and twice he passed his tongue between his lips. The fingers of his hand, gripping a chairback, opened and shut spasmodically. Rather feverishly his eyes searched the lawyer's face, questioning.

"John told you-told you-" he started, and floundered hopelessly.

"His lordship told me nothing, sir. He was singularly reticent. But there was nothing he could tell me that I did not already know."

"What do you mean, Warburton? Why do you look at me like that? Why do you fence with me? In plain words, what do you mean?"

Warburton rose, clenching his hands.

"I know you, Master Richard, for what you are!"

"Ah!" Carstares flung out his hand as if to ward off a blow.

Another tense silence. With a great effort Warburton controlled himself, and once more the mask of impassivity seemed to descend upon him. After that one tortured cry Richard became calm again. He sat down; on his face a look almost of relief, coming after a great strain.

"You learnt the truth. . . from John. He. . . will expose me?"

"No, sir. I have not learnt it from him. And he will never expose you."

Richard turned his head. His eyes, filled now with a species of dull pain, looked full into Warburton's.

"Oh?" he said. "Then you. . . ?"

"Nor I, sir. I have pledged my word to his lordship. I would not speak all these years for your father's sake-now it is for his." He choked.

"You. . . are fond of John?" Still the apathetic, weary voice.

"Fond of him? Good God, Master Dick, I love him!"

"And I," said Richard, very low.

He received no reply, and looked up.

"You don't believe me?"

"Once, sir, I was certain of it. Now-!" he shrugged.

"Yet 'tis true, Warburton. I would give all in my power to undo that night's work."

"You cannot expect me to believe that, sir. It rests with you alone whether his name be cleared or not. And you remain silent."

"Warburton, I- Oh, do you think it means nothing to me that John is outcast?"

Before the misery in those grey eyes some of Warburton's severity fell away from him.

"Master Richard, I want to think the best I can of you. Master Jack would tell me nothing. Will you not-can you not explain how it came that you allowed him to bear the blame of your cheat?"

Richard shuddered.

"There's no explanation-no excuse. I forced it on him! On Jack, my brother! Because I was mad for love of Lavinia- Oh, my God, the thought of it is driving me crazed! I thought I could forget; and then-and then-I met him! The sight of him brought it all back to me. Ever since that day I have not known how to live and not shriek the truth to everyone! And I never shall! I never shall!"

"Tell me, sir," pleaded Warburton, touched in spite of himself.

Richard's head sunk into his hands.

"The whole scene is a nightmare. . . . I think I must have been mad. . . I scarce knew what I was about. I-"

"Gently, sir. Remember I know hardly anything. What induced you to mark the cards?"

"That debt to Gundry. My father would not meet it; I had to find the money. I could not face the scandal-I tell you I was mad for Lavinia! I could think of nought else. I ceased to care for John because I thought him in love with her. I could not bear to think of the disgrace which would take her from me. . . . Then that night at Dare's. I was losing; I knew I could not pay. Gad! but I can see my notes of hand under Milward's elbow, growing. . . growing.

"Jack had played Milward before me, and he had won. I remember they laughed at him, saying his luck had turned at last-for he always lost at cards. Milward and I played with the same pack that they had used. . . . There was another table, I think. Dare was dicing with Fitzgerald; someone was playing faro with Jack behind me. I heard Jack say his luck was out again-I heard them laugh. . . . And all the time I was losing. . . losing.

"The pin of my cravat fell out on to my knee. I think no one saw it. As I picked it up the thought that I should mark the cards seemed to flash into my mind-oh, it was despicable, I know! I held the ace of clubs in my hand: I scratched it with that pin-in one corner. It was easily done. By degrees I marked all four, and three of the kings.

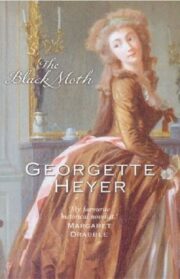

"The Black Moth" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Black Moth". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Black Moth" друзьям в соцсетях.