Alex’s father slipped the guinea from Alex’s nerveless fingers and handed it back to Lord Frederick. “You can settle accounts with the Governor General,” he said.

Alex didn’t need his father’s warning look to tell him that departure was the better part of valor. “If you’ll excuse me,” he said in a voice like granite, “I’ll go see to those arrangements. Lord Frederick, Lady Frederick. Cleave. Fiske.”

“Good man.” Lord Frederick favored him with a perfunctory nod before turning back to Fiske. “Now about that filly . . .” Alex heard him saying as he walked away.

Alex concentrated on putting one foot in front of another and breathing deeply through his nose. The Begum’s house was as familiar to Alex as his own quarters. He turned to the left, pushing open the door to the deserted book room. Behind him, he could hear the slap and shuffle of his father’s boots against the marble floor.

“Easy, my lad, easy,” warned his father, peering down the corridor and pushing the door shut behind them. “Keep a rein on that temper of yours.”

Alex regarded his father sourly. His father had many virtues, but restraint of any kind was not known to be one of them. Otherwise, Alex would never have had quite so many half-siblings.

Besides, he had no temper. He was a remarkably even-tempered man. Except in the face of sheer stupidity. Unfortunately, there seemed to be a good deal of that going around Calcutta.

“That,” Alex said pointedly, jerking his head towards the room they had just vacated, “is a disaster waiting to happen.”

“Just so long as you don’t allow it to happen to you,” returned his father equably. Beneath their wrinkled lids, his faded blue eyes were surprisingly shrewd. Self-indulgent he might be, but no one had ever called him stupid. “I’m within an ace of wrangling that district commissionership for you. So don’t go fouling it up out of some high-minded notion.”

At the moment, Alex was feeling more bloody-minded than high-minded. It was all very well for his father to counsel prudence, but as far as Alex could see, he was damned either way.

“Fine,” said Alex. “Let’s say I hold my tongue and cart Lord and Lady Freddy meekly off to Hyderabad a week Tuesday. What happens when that idiot sparks off a civil war? I doubt I’ll receive commendations when Mir Alam’s lads kick us out of Hyderabad, lock, stock, and barrel. With matters the way they stand, Wellesley’s new pet could undo in a moment what Kirkpatrick took six years to accomplish.”

His father regarded him patiently. “It’s not all on your shoulders, Alex.”

“Then whose?” Alex demanded, frustration ringing through his voice. “Wellesley doesn’t trust Kirkpatrick to piss without someone writing a secret report on it; Russell isn’t a bad sort, but he’s untried — ”

“ — and a bit too much in love with himself,” the Colonel humored him by adding.

Alex glowered at his father. Just because he had said it before didn’t make it any less true or any less problematic. “Precisely. The new Nizam is a tin-pot Nero who gets his amusement using silk handkerchiefs to throttle his concubines. He’ll go wherever Mir Alam tells him to, just so long as Alam doesn’t cut off his supply of expensive hankies and cheap women. And Mir Alam is half rotted with leprosy and demented with the desire to be revenged upon the British, because he blames us for his bloody exile four years ago.”

“It is unfortunate, that,” admitted his father.

“ ‘ Unfortunate’ doesn’t even begin to cover it. It’s a bloody fiasco. And do you know what makes it even worse?”

“No, but I’m sure you’ll tell me, lad,” said his father, patting him fondly on the shoulder.

Alex ought to have resented the pat, but he was too busy with his main rant to waste time on peripheral grievances. “It was Wellesley that bloody saddled us with Mir Alam! He met him years ago in Mysore and decided he was a good chap. But, no, he couldn’t be bothered to look into what might have happened in the interim! He’s too busy poking into Kirkpatrick’s bedchamber, like a bloody peeping Tom!”

“Whoa, there.” The Colonel’s hand tightened on his arm. “Keep your voice down. You don’t want to be losing your post for a moment’s ill-humor.”

“It’s more than a moment,” said Alex tiredly, feeling the rage wash out of him, leaving him feeling like a fish washed up on the beach. “It’s been months, ever since Wellesley pushed Mir Alam’s appointment as First Minister. And what’s the point of hanging on to my post if there’s nothing I can do with it? Except play lackey to a walking disaster,” he added bitterly. “It’s like being asked to play host to one’s own executioner.”

“Patience,” advised the Colonel.

“For what?” demanded Alex. “More of the same?”

Looking to the left and right, the Colonel tapped a finger against the side of his nose. “Word to the wise, my boy,” he said sotto voce. “It isn’t generally known yet, but the word is that Wellesley is on his way out. Apparently the folks back home on the Board of Control are none too happy with the Governor General’s expenditures.”

Alex looked at his father closely. “How ‘none too happy’?”

His father regarded him shrewdly. “Between the cost of the war with the Mahrattas and that grand Government House the Governor General has been building, they’re feeling the pinch in their purses, lad. You can guess how unhappy that makes them.”

Alex absorbed the information. “Is there any word on whom they might send to replace him?”

The Colonel shook his head. “It’s all just rumor, as yet. But if you get yourself disciplined before Wellesley goes, it won’t matter who the new man is.”

He would have to be right, wouldn’t he? Feeling like a small boy caught out in some petty carelessness, Alex inclined his head in the briefest of acknowledgments. “Point taken.”

His father clapped him on the shoulder, the reward after the scolding. “It will be all right, my boy, just you wait and see.”

“When do you sail?” Alex asked, deeming it wise to change the subject while he was still ahead.

Having served for four decades in the Madras Native Cavalry, his father had finally deemed it time to retire from active service. After a childhood in Charleston, a lifetime soldiering in India, and amours of various extractions, the Laughing Colonel, scourge of Madras, was retiring to Bath to be closer to his daughters. Alex’s Jacobite grandparents must be turning in their graves.

“That depends in part on you.” The Colonel paused to allow the impact of his words to sink in. Alex folded his arms across his chest, signaling to his father that he knew exactly what he was up to. Feigning obliviousness, the Colonel carried on innocently, “I shouldn’t like to go until I see you settled. Although it will be that glad I am to see Kat and Lizzy again.”

“Give them my love when you see them,” said Alex. It seemed a more manly way of saying good-bye than I’ll miss you .

As much as he hated to admit it, he would miss the old reprobate. His father might have had eccentric notions of family life, but they had been affectionate ones, for all that. The Colonel had never repudiated any of his offspring, no matter how irregular the circumstances. Of five living siblings, only Alex and his sister Kat were technically legitimate, but the Colonel had always treated all of his children with exactly the same rambunctious affection, no matter which side of the blanket they had tumbled out of. He had seen to their schooling and found placement for Alex in his own cavalry unit. For George, who was barred from the East India Company’s army by virtue of being the offspring of an Indian woman, he had wrangled a command in the service of a native ruler, the Begum Sumroo.

As a young man eager to make his own mark on the world, Alex had often found his father’s constant oversight irksome. He had left the cavalry for the political service, left Madras for Hyderabad, done everything he could to make his own way in his own way, gritting his teeth at the invariable “Oh, Reid’s boy, are you? Splendid chap!” that greased his way even as it did damage to his molars. But over the years, he and his father had come to a comfortable sort of understanding.

There was a curious emptiness that came with the thought that henceforth the old rascal would be a full five months away. He would miss him.

“You’ll keep an eye on George for me, won’t you?” said the Colonel.

Alex raised both eyebrows. “You’ve asked George the same about me, haven’t you?”

The Colonel stretched his arms comfortably in front him. “I like to see you all looking out for one another,” he said placidly. “It’s what a family is for.”

“Except Jack,” said Alex.

His father didn’t like to talk about Jack.

The Colonel’s bland smile didn’t wobble, but there was nothing he could do to hide the slight trembling of his hands. “That Lord Frederick Staines is a piece of work and no mistaking,” he said, changing the subject as though that was what they had been talking about all along, “but his wife seems to have a head on her shoulders.”

“I hadn’t realized it was her head that interested you,” said Alex, letting the subject of Jack drop. It wasn’t particularly pleasant for any of them.

“Now, now. I appreciate a witty woman as well as the next man. She seems like a feisty lass, with no nonsense about her,” announced the Colonel. “I like her.”

This did not exactly come as a surprise. “Have you ever met a woman you haven’t liked?”

After giving the matter deep consideration, the Colonel said triumphantly, “There was your sister’s governess . . . Miss Furnival, as she was.”

“She didn’t like you,” corrected Alex. “That’s not the same thing.”

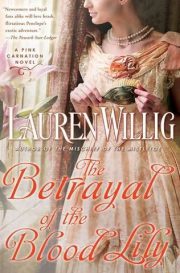

"The Betrayal of the Blood Lily" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Betrayal of the Blood Lily". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Betrayal of the Blood Lily" друзьям в соцсетях.