Once she rescued Alex from the idiocy of this duel, that would be the end of it, all obligations over on both sides. She had bullied him into dallying with her, and he had defended her out of duty. There was no point in falling into Charlotte’s fantasy land and deluding herself that it might ever be anything more.

A wild laugh tore out of Penelope’s throat. “I did something you wouldn’t approve of,” she blurted out, rounding towards her friend in a swirl of heavy fabric. “I committed adultery.”

There it was. No euphemisms. No pretense.

Penelope could tell Charlotte was horrified, even though she made a valiant effort to hide it. “I never thought you and Lord Frederick were well-suited,” she said diplomatically, before adding hastily, “not that I hoped he would get bitten by a snake, of course.”

“You don’t understand. I was with Alex — Captain Reid — while Freddy was dying. I didn’t know — I had no idea — ”

Charlotte lurched forward in her chair, her innocent face earnest. “But you couldn’t have known. Oh, Pen. How could you possibly have foreseen that something like that might happen?”

It was on the tip of Penelope’s tongue to tell her about Fiske. But she shrugged the impulse aside. Matters were complicated enough. “Bad things happen. If I hadn’t caused him to be exiled to India, he wouldn’t be dead.”

“Bad things can happen anywhere,” said Charlotte earnestly. “He might just as well have fallen off his phaeton or tripped into the Serpentine or been bludgeoned to death by footpads. You certainly didn’t mean any of this to happen when you — well, you know.”

“Just because I didn’t mean him to die from it doesn’t make it any less my doing.”

“Everyone dies eventually,” said Charlotte, looking down into the clouds created by the milk in her tea. In a barely audible voice, she added, “No matter how much one wishes otherwise.”

Not even Charlotte could muster that much sympathy for Freddy. With a jolt, Penelope realized that Charlotte was not thinking of Freddy, but of her parents. She spoke of them so seldom that it was easy to forget how deeply she had been attached to them.

Feeling beastly, Penelope plopped into the chair next to her friend’s. “I’m sorry, Lottie.”

“Don’t be.” After a moment, Charlotte looked up from her tea, her eyes as bright and curious as a sparrow’s. “Do you love him?”

“Who?”

“Captain Reid,” said Charlotte, as though it were entirely obvious.

Perhaps it was.

“I don’t know,” said Penelope bleakly. “I don’t know what love is.”

All she knew was that she couldn’t let him perish on the field of honor tomorrow morning. It would be worse than what she had done to Freddy, worse than anything she had ever done or could do.

“Do you know,” said Charlotte, addressing herself to the sugar bowl, “I believe that’s the closest I’ve ever heard you come to making a declaration of affection.”

“Over my husband’s corpse,” said Penelope darkly.

Charlotte sighed. “You never do do anything in the ordinary course, do you?”

Chapter Twenty-Eight

Freddy managed to be quite as much bother in death as he had been in life.

James Kirkpatrick, the Resident, went gray when he heard the news, tugging at his carefully cultivated mustachio as he murmured the proper words of condolence, his mind all the while obviously already working over the phrasing of diplomatic dispatches. How did one tell Wellesley that his pet had perished in the wilderness four days north of Hyderabad?

Penelope didn’t envy him the task, although she would gladly have traded his for hers, the letters Charlotte had reminded her were due to both Freddy’s mother and her own.

It fleetingly occurred to her that she would never be able to go back to London. Well, not never. But not for a very long time. She had no desire to spend her remaining days shrouded in widow’s weeds, to face the anger and accusations of Freddy’s family and the opprobrium of her own, returning to the family home where her mother would have free rein to vent at her all the rage of her thwarted ambitions.

No, she couldn’t go back to London. What was odder was that the thought brought with it no regret.

England and their respective families seemed very far away. In the confused days after Freddy’s death, Penelope hadn’t thought about that. She hadn’t thought about a lot of things. It was the Resident’s task to remind her, ably seconded by Charlotte, who fluttered and fussed and produced enough tea to keep the servants permanently engaged in emptying chamber pots. There were funeral arrangements to be seen to — sooner, rather than later, as the Resident intimated with charming delicacy.

“You mean he’s beginning to rot,” Penelope said bluntly, to which the Resident had replied, with a diplomat’s tact, “In hot climates, funerals tend to be held sooner than those to which we are accustomed. As it has already been several days . . .”

They arranged for the funeral and a myriad of administrative details, as Henry Russell made notes and a variety of functionaries were sent back and forth on various related tasks. Alex was sent for at one point, something about official representations of Freddy’s death to the Nizam and pacifying Mir Alam for the non-arrival of his guests, but the servant sent on that errand returned with the news that Captain Reid had gone into the town and hadn’t left word when he would return.

Securing his second for the meeting the next day? Penelope wondered where Fiske had got to.

The Resident said something, loudly, and Penelope realized that they were all looking at her, waiting for her to respond to a question that had been asked twice, or even three times.

“I’m sorry,” Penelope said. “I’m afraid I was elsewhere.”

A look of insufferable understanding passed between Russell and Kirkpatrick. “No matter,” the Resident said kindly. “If you would prefer to retire . . .”

Penelope stiffened her spine. “No. No. Carry on.”

She knew they were watching her, waiting for signs of the anticipated breakdown, the grieving widow’s grieving. It would be the womanly and proper thing to do. But she had had her hysterics already, in the caravan courtyard the day before. She had had four days to walk through her shock and guilt and despair. All she wanted now was to get it done with, to have the arrangements arranged and Freddy safely in the earth.

“I have ordered a room prepared for you in the Residency,” the Resident said delicately, as they rose after what seemed a very long time.

It was a kindly gesture, even if misplaced. It served her current purposes perfectly. It would be easier to incapacitate Fiske if she was spending the night beneath the same roof.

“Thank you,” she said demurely, as they passed through a high ceilinged room that lay still and dark in the evening cool. “I shall take supper in my room.”

She could sense the approval from her entourage. It was the sort of thing a grieving widow was supposed to do. It also left her free to hunt down Fiske.

“I shall see that — ,” the Resident began, and broke off to dart forward as Charlotte, who had been walking a little way ahead, suddenly launched herself into the air, flailing her arms madly for balance.

“Oooph!” she said descriptively, as the Resident caught her neatly around the waist, preventing her from pitching over.

As Charlotte grimaced at him apologetically, Penelope discreetly rolled her eyes. Charlotte had a habit of collisions with inanimate objects; her mind and her body seldom kept company together on their various wanderings, leaving her prone to tripping over anything that wasn’t wise enough to get out of her way first. Rolled-up carpet edges and small tables were not known for their self-preserving instincts.

“I’m so sorry,” Charlotte said brightly. “I seem to have tripped over . . . Oh. Oh, dear.”

Her fair skin went waxy in the uneven light of the candles. The Resident hastily stepped between her and whatever it was, shielding Charlotte’s tender sensibilities. He also obstructed Penelope’s view.

Charlotte swallowed hard. “Oh, dear,” she repeated.

Penelope elbowed her way forward. There, in the flickering light, she saw the body of a man sprawled facedown on the Turkey rug. It was hard to tell what color his hair had been; it was matted with the blood that seeped from the gash in his skull. There was a ring on his outstretched hand, large and flashy with the incised lines of a lotus flower riven onto a ruby surface. Penelope recognized it as belonging to Fiske. Freddy had owned a similar one, insignia of the club to which they had both belonged.

That past tense suddenly sounded particularly significant.

“Call Dr. Ure,” said the Resident sharply. He bent over the body. When he straightened, there was an expression of inestimable relief on his face. But all he said was, “He breathes.”

There were pounding feet, behind them, the sound of bodies being dispatched and arriving.

As for Penelope, she was conscious of a distinct and ignoble sense of relief that someone had put Fiske out of commission before she had been required to do so. A man with a head wound couldn’t very well put in a dawn appearance on a dueling field.

“He might be breathing now, but for how long?” demanded Jasper Pinchingdale loudly, shouldering his way to the front of the group. “That’s the devil of a nasty head wound. And who did it?”

“Perhaps he fell,” suggested Charlotte innocently.

“And struck himself on the head with a candlestick in falling?” said Penelope, relief taking vent in sarcasm.

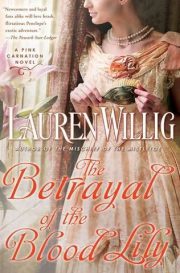

"The Betrayal of the Blood Lily" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Betrayal of the Blood Lily". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Betrayal of the Blood Lily" друзьям в соцсетях.