It wasn’t a photo. But it also quite definitely hadn’t been on the floor before. It was the beginning of a letter, written on thick, cream-colored stationery with Mrs. Selwick-Alderly’s name embossed on the top. I couldn’t see who it was addressed to; this must have been the second page, and only a draft, at that. It was heavily crossed out and interlined, in a way I would never have expected of my fastidious hostess. But she had clearly been in the grip of some strong emotion while writing the letter. The first full line, written ruler straight across the top of the page, read, “To act on something that must cause those who love you so much unhappiness can only be accounted the most base self-indulgence.”

There it was again, that word, “self-indulgence.”

I tried to remember why it sounded so familiar, why I could hear Mrs. Selwick-Alderly pronouncing it so clearly in my head. After a moment, the memory snapped into place. That was how she had referred to Colin’s mother, condemning free spirit as merely another term for self-indulgence.

With renewed interest, I peered down at the piece of paper. The cross-outs made it hard to read, but the next line read, “I should not have thought that even you could be so blindly selfish as to leave two grieving children deprived not only of a father, but of a mother, too. If you will not think of William, think at least of them and temper your own desires for the space of ” — she had crossed out at least five alternative word choices, finally settling upon — “for a space in which reason and moderation might prevail. What seems imperative today may not be so tomorrow, and in the process, how many lives affected? I should not take it upon myself to interfere into your personal affairs upon a mere whim, but this — ”

Here the writer’s words failed her in a sea of black ink. I could see the spiky b, t, and l of “betrayal” poking out among the general blackout, but the rest was unclear. Betrayal. It seemed an unusually strong word. There was stronger to come, under the wash of black ink. I squinted at the heavily scratched-out lines, trying to make out the letters. Was that “treason” there, a little after “betrayal”? I couldn’t quite tell.

The letter picked up again in a calmer vein, as if the storm of emotion had washed itself out. “If you must — as, indeed, I hope you will not — a space of time abroad would seem the wisest course.” Her pen had faltered on the word “wise,” as though doubtful as to its use in that context. “But I hope you will not. Do not make me ashamed to call you my — ”

A creaking sound down the hall jarred me out of my absorption. I banged my head against the mattress in my haste to stuff the letter back into the pages of the album, return the album to the box, and dispose myself innocently back among the Indian notebooks, breathing as quickly as though I had just been caught with my hands in my hostess’s jewel box. Mrs. Selwick-Alderly might be indulgent enough about my foray in search of photos of an adorable, small Colin, but I doubt she would feel the same way about my reading her personal correspondence, especially correspondence such as that was.

I grabbed up a notebook at random and plunked it open on my lap, just in time. The door swung open on a widening arc, and a sleek brown head poked through.

“Oh!” I exclaimed, forgetting to try to look scholarly and absorbed. “Hi!”

Serena kept one hand on the door, as though unsure of her welcome. “I didn’t mean to disturb you,” she said, hovering in the door frame. “Please don’t mind me. I just came to collect a pair of earrings from Aunt Arabella.”

I half-scrambled, half-slid off the bed, my wool pants tugging up against my calves as I slithered down. “You’re not bothering me at all. I was just about to call it a day anyway, before I overstay your aunt’s hospitality.”

As I said it, I realized it was true. The early dusk of winter had fallen, leaving it full dark outside, bringing into relief the cheerful circle of light cast by the bedside lamp. From across the way, I could see the dim reflection of a television screen through the window. It must be getting on towards dinnertime, at least. Judging from the profusion of cream-colored cardboard cards on the mantel, I wouldn’t be surprised if Mrs. Selwick-Alderly had evening plans. She had let me stay behind to keep on researching while she went out once before, but I couldn’t expect her to make a habit of it. No matter how nice she was being about it, it was still an imposition.

On an impulse, I asked Serena, “What are you up to tonight?”

Serena ventured a small, shy smile. “Watching Emmerdale ?”

I wasn’t entirely sure, but I rather thought that we might just have shared a private joke. It shouldn’t have surprised me that Serena had a sense of humor — according to Pammy, she had been very clever in school — but I had never had a chance to see it before. Probably because I was generally talking. Or Colin was there, and — let’s be fair — when Colin was around, I didn’t notice terribly much about anyone else.

“What would you say to a movie? There’s the new James Bond playing at the theatre in Whiteley’s. I guess that’s pretty out of your way, though.”

“No, I’d love to go,” said Serena hastily, pushing her hair out of her face with both hands. “Unless — that is — unless you’d rather wait and see it with Colin.”

“Not at all,” I said firmly. “He doesn’t need to see me drooling over Pierce Brosnan. It might hurt his feelings.”

I got a full-fledged smile that time.

I waved my mobile in the air. “I’ll just check for show times.” Our breath misting in the cold night air, we bundled into a cab. I almost never took cabs — a student stipend only stretches so far — so it felt wonderfully decadent to be coasting off into the night in a big black car to indulge in gratuitous entertainment in the middle of the week. The sharp air had brought a tint of bright color to Serena’s thin cheeks. We scrambled into the back of the cab in a flurry of high heels and dropped gloves and trying to figure out who had accidentally sat on whose coat in the confusion of scooting across the black leather banquette.

We gave the cabbie the address and plopped back, with breathless laughter, against the back of the seat in the cozy, dark interior. We were going to the big multiplex in Leicester Square rather than the one in the Whiteley’s shopping center, since we had already missed one and were too early for the other at Whiteley’s. Besides, it somehow seemed more equitable to go to a theatre that would be equally inconvenient for both us, for Serena in Notting Hill and for me in Bayswater.

“I hope this one is good,” I said, twisting to sit sideways with one arm against the back of the seat. “Thanks for saying you’d come with me.”

“Did you find what you were looking for at Aunt Arabella’s?” Serena asked politely.

“Sort of,” I said. “I think so.”

It might have helped if I could have said with any certainty what it was I had been looking for. Popular legend ascribed to the Pink Carnation various exploits in India, although neither the contemporary media accounts nor the scholarly sources had been terribly clear about what those exploits were meant to be. All that I knew was that the Pink Carnation was meant to have done something, somehow, in India. I had always wondered how he (back when I started my dissertation I had still assumed the Pink Carnation must be a he, arrogantly supposing that the Pink might even be a clever play on the phrase “pink of the ton ” generally ascribed to dandies and the like) had managed that, when India was a six-month journey by boat. Each way. How would the Pink Carnation have had time to get to India, foil a dastardly French plot, unravel a league of spies, and then get back to Europe in time to meddle in Napoleon’s coronation plans? It had never made any sense to me. Given the lack of such conveniences as telephones, fax machines, and FedEx, it didn’t seem quite likely that the Pink Carnation would have been able to pass along orders remotely.

But it looked as though at least one aspect of the legend was being borne out. There had been a French spy ring in India and it had still been extant as late as 1804. For those non-historians out there, that in itself was a significant coup. Most people tend to just ignore India in the context of the Napoleonic Wars after 1799, assuming that once Napoleon got his unmentionables kicked in Egypt, that part of the world just ceased to be in play.

The system of flower names did seem to imply some sort of cohesive, overall organization, unless, of course, the Indian group was merely copycatting off their European counterparts. But who was organizing them? They might have been a part of the Black Tulip’s empire, autonomous now that the Black Tulip had — presumably — gone to his reward. But the Black Tulip had specialized in petals, not in other flowers. I had the uneasy sense of having stumbled onto something far larger than I had anticipated and I had no idea at all where it was going.

If I were sensible, I would give the whole idea a miss. I would stick to the dissertation outline I had already submitted to my advisor, focusing entirely on the spies’ European operations, without branching into the hinterlands.

But I was curious. Let’s be honest, I was also looking for excuses to avoid writing up what I already had. Needing more research is always a brilliant reason to postpone actually writing your dissertation. After all, no one can accuse you of being lazy when you’re working. There’s a reason why you meet fifteenth-year grad students still diligently puttering away in the archives, amassing huge stockpiles of entirely undigested information. I knew one guy who spent nine years filling five file cabinets with notes without ever writing a single page of his dissertation.

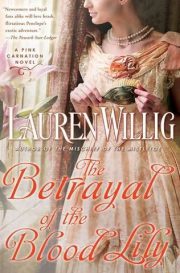

"The Betrayal of the Blood Lily" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Betrayal of the Blood Lily". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Betrayal of the Blood Lily" друзьям в соцсетях.