“These,” said Mrs. Selwick-Alderly with great satisfaction, “should be precisely what you were looking for.”

Were they? I tried not to look too dubious.

Perching on the edge of the bed next to the box, she explained, “I spent a winter at the Residency at Karnatabad — oh, years and years ago. Karnatabad was a British construct,” she added briskly, “a district drawn up out of the Ceded Territories, the lands ceded by the Nizam after the second Mahratta War. Lady Frederick’s papers were kept in the archives there. Such a mess they were, too! Generation after generation had simply stuffed books and papers onto shelves without making the least effort to sort them.”

I nodded vigorously in sympathy. I had visited records offices like that in England, including one, which shall remain nameless, where the archivist plaintively asked me if I would mind making a record of whatever papers I came across as I sifted through them since he had never gotten around to doing it himself.

“These notebooks,” said Mrs. Selwick-Alderly, peering down fondly into the box, “are my gleanings from that chaos.”

I couldn’t resist asking. “What made you decide to, er, glean?”

A flicker of a smile showed around Mrs. Selwick-Alderly’s lips. “I used to think I wanted to write a novel,” she said, as though it were a great joke. “Mollie Kaye and I both had grand ideas of writing an Indian epic. She actually did it, though.”

Mollie Kaye . . . “You knew M. M. Kaye?” I yelped.

Mrs. Selwick-Alderly nodded, a gentle smile on her lips, as though she were hearing the echoes of conversations once spoken in places that no longer exist. “Yes. We all had a sense, in those days, that the world around us — British India as it had been — was vanishing, and that it was expedient to record as much as we could before it disappeared entirely. It lent a certain urgency to the exercise. And a good thing, too.” Mrs. Selwick-Alderly patted the side of the box fondly. “Not long after my stay in Karnatabad, the Residency was renovated for use as a school and the archives were lost. Someone told me that much of it was simply thrown out. They hadn’t the resources for keeping it,” she said with a sigh, before adding briskly, “Although, of course, primary education was a far more important concern.”

“Of course,” I agreed. And then, because I couldn’t resist, “What was your novel going to be about?”

“Dashing spies,” she said lightly, getting up off the bed. “What else?”

What else, indeed? I wondered if she knew that her great-nephew was currently engaged in writing a spy novel. Or, at least, that was what he claimed. There were still times when I couldn’t help but wonder whether his interest in spies was more than literary. Pretending to write a spy novel could make a very clever cover for other sorts of activities.

“I’ll leave you to it, then. If you have any trouble with the handwriting, don’t hesitate to find me. I have no doubt that the ink is rather faded by now.”

Thanking her, I divested myself of my boots and scrambled up onto the high old bed, tucking my stockinged feet up beneath me. I tentatively lifted the first notebook out of the box. Number Fifteen. Mrs. Selwick-Alderly certainly had been methodical. On the front leaf, she had listed the date she had transcribed it, the translator she had hired to transpose the non-English documents, and the dates and authors of the historical records. If I were half that organized, I would have my dissertation long since done already.

Digging through for a notebook labeled “1,” I found one without any number on it at all. Opening it at random, I saw, in Mrs. Selwick-Alderly’s slanted handwriting, “She waited, breathless, in the lee of Raymond’s Tomb as the dark line of conspirators rode past. To be found would be death.”

Hmm. She hadn’t been joking about that novel, then. I looked speculatively at the notebook. I wondered what would have happened if she had finished it. There were so many novels set around the Indian Mutiny of 1857, but it was hard to think of any set those fifty-odd years earlier, during the Mahratta Wars. It would make a good landscape for fiction.

It also made a good landscape for a dissertation chapter, I reminded myself, forcing myself to put aside the unfinished novel (working title: Shadow of the Tomb ). Clicking on the bedside lamp, which sent a pleasant pool of light across the counterpane, I curled up against the pillows with Notebook 1, a compilation of various letters and dispatches sent by Henry Russell, the exceedingly prolific Chief Secretary to the Resident of Hyderabad.

According to Russell, the Resident had been tearing out his hair about the presentation of the new Special Envoy, Lord Frederick Staines, to the Nizam of Hyderabad at a durbar called for that purpose. No one knew quite what the unpredictable new Nizam might do. The same went for Lord Frederick, who spoke no Persian and had a worrying lack of knowledge about proper court protocol. Embassies had been banished for less.

And to make matters even worse, his wife had insisted on coming along.

Chapter Eight

“What is she doing here?” Alex demanded, as Lady Frederick climbed out of the Resident of Hyderabad’s state palanquin.

The state palanquin, in which James rode with the new Special Envoy, was a testament to what raw money and talented craftsmanship could provide. The tasseled silk curtains, however, hid as much as they concealed. In this case, the presence of an extra individual in the palanquin.

For the duration of the ceremonial procession from the Residency to the Nizam’s fortress, Alex had trotted blithely along beside the palanquin, entirely unaware that the tasseled curtains concealed an additional passenger. Only the Resident and the new Special Envoy had been bidden to the Nizam’s durbar. It had never occurred to Alex — or, he imagined, the Nizam — that the Special Envoy’s wife might take it upon herself to attend as well.

Alex gritted his teeth in a way that boded ill for his dental health. One did not just drop by on a supreme ruler unannounced. Especially not a supreme ruler with a penchant for extemporaneous executions.

All around them, armed guards in steel helmets and gauntlets stood at attention, their bearded faces impassive. There had been more guards than usual in the Nizam’s palace, Alex had noticed, stationed in all of the courtyards through which they had passed on their way to the durbar at which Wellesley’s new Special Envoy was to be formally presented to the Nizam.

They had guards enough of their own. The Resident and Lord Frederick had made their way from the Residency complex on the other side of the river accompanied by no fewer than ten companies of infantry, along with five brightly bedecked elephants, a troop of cavalry, and two dozen riderless horses whose sole purpose was to show off brightly colored pennants. After a lifetime in Indian courts, James Kirkpatrick knew how to put on a show.

Would a show be enough to secure their safety in this new and dangerous political climate?

Alex had thought he had addressed his question to the Resident sotto voce. Unfortunately, the acoustics in the courtyard were excellent.

Lady Frederick swept towards him in a whisper of white satin, like moonlight on marble and just as cold. “And a good evening to you, too, Captain Reid. I had thought I might have trouble recognizing you after all this time, but your charm is unmistakable.”

“I’ve been busy,” he said stiffly. And he had been. Since returning two weeks ago, he had taken half his meals in the saddle or at his desk.

There was no reason he should feel guilty about neglecting his former charge. It wasn’t as though she was likely to lack for entertainment. Since their arrival, nearly every family in the Residency had felt it incumbent on themselves to throw a dinner or a card party or a Venetian breakfast for the new arrivals. Alex had avoided all the entertainments with impartial firmness, pleading the very real pressures of work.

And since when had she become his , just because he had been saddled with the task of getting her husband from Calcutta to Hyderabad? His obligation to Lady Frederick Staines had ended at the Residency gates, and that was that.

Or that should have been that. Over the past two weeks, Alex had found that he couldn’t quite purge Lady Frederick from his thoughts. Without seeing or consulting her, he had arranged for an Urdu tutor to be sent to her, hoping that would quell his conscience. It hadn’t. He still felt, for some inexplicable reason, obscurely responsible for her, a sensation that even consistent avoidance hadn’t managed to expunge entirely.

It wasn’t as though that were unusual, Alex rationalized to himself. George might have carted home stray dogs, but he was the one who had been left caring for them. This was exactly the same. Lady Penelope was just another stray who had been dumped into his care, like George’s pariah dogs or that one-eared kitten Lizzy had dragged home.

The analogy was an unfortunately apt one. Like Lizzy’s kitten, Lady Frederick seemed determined to sharpen her claws. On him.

“I’m sure you have been,” Lady Frederick agreed with deceptive complaisance. “There are so many things to keep one busy, aren’t there?”

Alex had the feeling he was being accused of something more than neglect, but he couldn’t imagine what. “Look,” he said, with a nod towards the archway. “Someone’s come to fetch us.”

It should, for courtesy’s sake, have been the Nizam’s chief minister, Mir Alam. Instead, it was a palace functionary so minor that Alex didn’t even know his name. From the expression on James’s face, he didn’t either. The Resident was not best pleased, but there was little he could do about. His own position was too precarious.

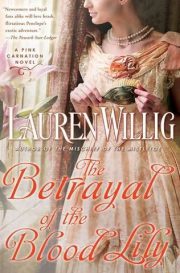

"The Betrayal of the Blood Lily" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Betrayal of the Blood Lily". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Betrayal of the Blood Lily" друзьям в соцсетях.