The specter of death always loomed over us.

Come in for a while, Sensei said. Have some tea, he said as he led the way inside. The small I ♥ NY logo was also printed on the back of Sensei’s T-shirt. I read it aloud while I took off my shoes.

So, you wear pajamas, Sensei? I would have thought you wore nemaki, I muttered as I trailed after him, referring to Japanese-style sleepwear.

Sensei turned to face me. Tsukiko, please refrain from commenting about my clothing choices.

Yes, I answered quietly.

Very well, then, Sensei replied.

The interior of the house was damp and quiet. A futon was laid out in the tatami room. Sensei took his time making the tea and he took his time serving it to me. For my part, I lingered over my cup, drawing out the minutes.

Several times, I called out, “Sensei,” and each time, Sensei would reply, “What is it?” I wouldn’t say anything in response, until the next time I called out, “Sensei.” It was all I could manage.

Once I had finished drinking my tea, I took my leave.

“Please take good care of yourself.” I bowed politely at the front door.

“Tsukiko.” This time Sensei was the one to say my name.

“Yes?” I raised my head, looking Sensei in the eye. His cheeks were sunken and his hair was tousled.

“Get home safely,” Sensei said after a moment’s pause.

“I’ll be fine,” I replied, rapping on my chest.

I closed the front door to prevent Sensei from walking me to the gate. A half-moon hung in the sky. Dozens of insects were chirping and buzzing in the garden.

I’m so confused, I muttered, leaving Sensei’s house.

I don’t care anymore. About love or anything. It doesn’t matter what happens.

In truth, it really didn’t matter. As long as Sensei was fine and well, that’s what was important.

This was enough. I would stop hoping for anything from Sensei, I thought to myself as I walked along the road by the river.

The river flowed along, silently, to the sea. I wondered if right now Sensei was nestled in bed, in his T-shirt and his pajama pants. Was his house locked up properly? Had he turned out the light in the kitchen? And checked the gas?

“Sensei,” I breathed his name softly, in lieu of a sigh.

“Sensei.”

The air rising off the river carried a crisp hint of autumn. Goodnight, Sensei. You looked quite nice in your I ♥ NY T-shirt. Once you’re all better, let’s go for drink. Fall is here, so at Satoru’s place there will be warm things to eat while we drink.

Turning to face toward Sensei, who was now several hundred meters away, I kept on speaking to him. I walked along the length of the river, as if I were having a conversation with the moon. I kept talking, as if forever.

In the Park

I WAS ASKED out on a date. By Sensei.

I find it awkward to use the word “date,” despite the fact that the two of us had gone on that trip together (though, of course, we hadn’t actually been “together”), but we had plans to go to an art museum to see an exhibit of ancient calligraphy, which may sound like the kind of thing students would do on a school trip, yet nevertheless, it was a date. Sensei himself had been the one to say, “Tsukiko, let’s go on a date.”

It had not been in the drunken fervor at Satoru’s place. It had not been a coincidental meeting on the street. Nor did it seem to be because he happened to have two tickets. Sensei had called me up (however it was that he got my phone number) and, straightforward and to the point, he had said, “Let’s go on a date.” Sensei’s voice had a more mellow resonance over the phone. Perhaps it was because the sound was slightly muted.

We arranged to meet on Saturday in the early afternoon. Not at the station near here but rather in front of the station where the art museum was, two train lines away. Apparently, Sensei would be busy with something all morning but would then head toward the station by the art museum.

“It’s such a big station that I’m a bit worried about you getting lost, Tsukiko,” Sensei laughed on the other end of the line.

“I won’t get lost. I’m not a little girl anymore,” I said, and then, not knowing what else to say, I fell silent. On the phone with Kojima (we had spoken on the phone more often than we had seen each other), I had always been so relaxed, yet talking to Sensei now, I felt terribly ill at ease. When we were sitting next to each other in the bar, watching Satoru as he moved about, if the conversation lulled, it didn’t matter how long the silence lasted. But on the phone, silence yawned like a void.

Um. Yes. Well. These were the catalog of sounds I uttered while on the phone with Sensei. My voice got smaller and smaller and, although I was happy to hear from Sensei, all I could think about was how soon could I get off the phone.

“Well, then, I’m looking forward to our date, Tsukiko,” Sensei said in closing.

Yes, I replied in a faint voice. Saturday afternoon, at the ticket gate. One thirty, sharp. Rain or shine. So, I’ll see you then. Good day.

After the call ended, I sat sprawled on the floor. Soon there was a soft blare from the receiver I still held in my hand. But I just sat there, not moving.

ON SATURDAY, THE weather was clear. The day was warm for fall, so warm that even my not-so-thick long-sleeved shirt felt too heavy. I had learned my lesson on our recent trip, and decided against wearing anything that I wasn’t comfortable in, like a dress or high heels. I wore a long-sleeved shirt over cotton pants, with loafers. I knew Sensei would probably say I was dressed like a boy, but so what.

I had given up worrying about Sensei’s intentions. I wouldn’t get attached. I wouldn’t distance us. He would be gentlemanly. I would be ladylike. A mild acquaintance. That’s what I had decided. Slightly, for the long term, and without expectations. No matter how I tried to get closer to him, Sensei would not let me near. As if there were an invisible wall between us. It might have seemed pliant and obscure, but when compressed it could withstand anything, nothing could get through. A wall made of air.

The day was quite sunny. Starlings were huddled close together on the electrical wires. I had thought they only gathered like that at dusk, but there were flocks of them lined up on the electrical wires all around, and it was still early in the day. I wondered what they were saying to each other in bird language.

“They do make a ruckus, don’t they?” Suddenly a voice seemed to come down from above—it was Sensei. He was wearing a dark brown jacket, with a plain beige cotton shirt over light brown trousers. Sensei was always rather smartly dressed. He would never wear anything trendy like a bolo tie.

“Looks like fun,” I said. Sensei gazed up at the flock of starlings for a moment. Then he looked at me and smiled.

“Shall we go?” he said.

Yes, I replied, my gaze downward. All he had said was “Shall we go?” in the same voice as always, but I felt strangely emotional.

Sensei paid for our admission. When I tried to hand him money, he shook his head. No, please, I invited you, he said, refusing to take it.

We entered the art museum together. It was surprisingly crowded inside. I was amazed that so many people could be interested in completely indecipherable calligraphy from the Heian and Kamakura eras. Sensei stared through the glass at the rolled letter papers and hanging scrolls. I watched Sensei’s back.

“Tsukiko, isn’t this simply lovely?” Sensei was pointing at what appeared to be a letter with fluttery script written in pale ink. I couldn’t make out a word.

“Sensei, can you read this?”

“Ah, actually, I can’t really,” Sensei said with a laugh. “But still, it really is a nice hand.”

Do you think so?

“Tsukiko, when you see a handsome man, even if you cannot understand what he says, you still think, ‘Oh, that guy’s good-looking,’ don’t you? Handwriting is the same.”

I see, I nodded. Did that mean when Sensei saw an attractive woman, he thought, “Oh, what a pretty girl”?

After looking at the special exhibition on the second floor, we went back downstairs to view the permanent collection, and by then two hours had passed.

The calligraphy was utter gibberish to me, but I found myself enjoying the time as I listened to Sensei’s murmured bursts of “Such a nice hand” or “A bit prosaic” or “Now that’s what’s called a vigorous style.” The same way as when you’re sitting at a sidewalk café, furtively passing judgment on people as you watch them go by, it was amusing to attach my own impressions to these calligraphed works from the Heian or Kamakura eras: “That’s nice” or “This one’s not bad” or “It reminds me of a guy I used to go out with.”

Sensei and I sat down on a sofa on the staircase’s landing. Numerous people passed before us. Tsukiko, was that boring for you? Sensei asked.

No, it was rather interesting, I replied, staring at the backsides of the people passing by. I could feel the warmth radiating from Sensei’s body. The stirring of emotion returned. The hard sofa with bad springs felt like the most comfortable thing in the world. I was happy to be here like this with Sensei. I was simply happy.

“TSUKIKO, IS SOMETHING wrong?” Sensei asked, peering at my face.

Walking alongside Sensei, I had been muttering to myself, “Hopes strictly forbidden, hopes strictly forbidden.” I was mimicking the main character in the book The Flying Classroom, which I read when I was little, who says, “Crying strictly forbidden, crying strictly forbidden.”

This may have been the closest I had ever walked beside Sensei. Usually Sensei went in front of me, or I darted ahead—one or the other.

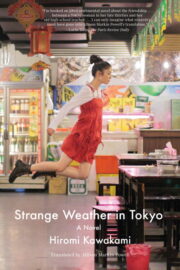

"Strange Weather in Tokyo" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Strange Weather in Tokyo". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Strange Weather in Tokyo" друзьям в соцсетях.