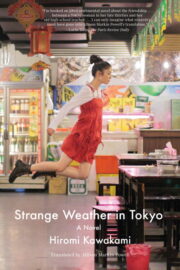

Hiromi Kawakami

STRANGE WEATHER IN TOKYO

The Moon and the Batteries

HIS FULL NAME was Mr. Harutsuna Matsumoto, but I called him “Sensei.” Not “Mr.” or “Sir,” just “Sensei.”

He was my Japanese teacher in high school. He wasn’t my homeroom teacher, and Japanese class didn’t interest me much, so I didn’t really remember him. Since graduation, I hadn’t seen him for quite a while.

Several years ago, we sat beside each other at a crowded bar near the train station, and after that, our paths would cross every now and then. That night, he was sitting at the counter, his back so straight it was almost concave.

Taking my seat at the counter, I ordered “Tuna with fermented soybeans, fried lotus root, and salted shallots,” while the old man next to me requested “Salted shallots, lotus root fries, and tuna with fermented soybeans” almost simultaneously. When I glanced over, I saw he was staring right back at me. I thought to myself, Why do I know his face…? Sensei spoke.

“Excuse me, are you Tsukiko Omachi?”

Surprised, I nodded in response.

“I’ve spotted you here sometimes,” Sensei said.

“Is that right?” I answered vaguely, still looking at him. His white hair was carefully smoothed back, and he was wearing a starched white shirt with a gray vest. On the counter in front of him, there was a bottle of saké, a plate with a strip of dried whale meat, and a bowl that had a bit of mozuku seaweed left in it. I wondered who this old man was who shared the same taste as me, and an image of him standing at a teacher’s podium floated through my mind.

Sensei had always held an eraser in his hand when writing on the blackboard. He would write something in chalk, like the first line of The Pillow Book by Sei Shonagon: In spring it is the dawn that is most beautiful. And then, not five minutes later, he would erase it. Even when he turned to lecture to his students, he would still hold on to the eraser, as if it was attached to his sinewy left hand.

“It’s unusual to see a woman alone in a place like this,” Sensei said as he delicately poured vinegared miso over the last morsel of dried whale and brought it to his lips with his chopsticks.

“Yes,” I replied, pouring beer into my glass. I had identified him as one of my high school teachers, but I still couldn’t recall his name. As I drained my glass, part of me marveled that he could remember the name of a particular student, and part of me was puzzled.

“Didn’t you wear your hair in braids during high school?”

“Yes.”

“I recognized you as soon as I saw you here.”

“Oh.”

“Did you recently turn thirty-eight this year?”

“I’m still only thirty-seven.”

“I’m sorry, I beg your pardon.”

“Not at all.”

“I looked you up in the register and the yearbook, just to be sure.”

“I see.”

“You look just the same, you know.”

“You look just as well, Sensei.” I called him “Sensei” to hide the fact that I didn’t know his name. He has been “Sensei” ever since.

That evening, we drank five bottles of saké between us. Sensei paid the bill. The next time we saw each other at the bar and drank together, I treated. The third time, and every time thereafter, we got separate checks and paid for ourselves. That’s how it went. We both seemed to be the type of person who liked to stop in every so often at the local bar. Our food preferences weren’t the only things we shared; we had a similar rhythm, or temperament. Despite the more than thirty-year difference in our ages, I felt much more familiar with him than with friends my own age.

I WENT TO Sensei’s house several times. Every so often we would leave our usual bar to drink at a second place, and then we would go our separate ways home. But the few times we got as far as a third or fourth bar, we inevitably ended up having the final drink at Sensei’s house.

“I live nearby, why don’t you come over?” Sensei said the first time he invited me to his home, and I felt a twinge of reticence. I had heard that his wife had passed away. The idea of spending time at a widower’s home was slightly off-putting, but once I’ve started drinking, not much can stop me, so I went along.

It was more cluttered than I had imagined. I had thought his place would be immaculate, but there were things piled up in every dark corner. Just off the hall, a carpeted room with an old sofa was absolutely silent and gave no hint of the books and writing paper and newspapers strewn about the adjacent tatami room.

Sensei pulled out the low dining table and took a large bottle of saké from among the things in a corner of the room. He filled two different-sized teacups to the brim.

“Please have a drink,” Sensei said before he headed off to the kitchen. The tatami room gave on to a garden. Only one of the rain shutters was open. Through the glass door I could see the vague shape of tree branches. Since they were not in flower, I couldn’t tell what kind of trees they were. I’ve never known much about plants.

“What kind of trees are those in the garden?” I asked Sensei as he carried in a tray with flakes of salmon and kaki no tane rice crackers.

“They’re all cherry trees,” he answered.

“All cherry trees?”

“Yes, all of them. My wife loved them.”

“They must be beautiful in the spring.”

“They are crawling with insects. In the fall there are dead leaves all over the place, and in winter the bare branches are bleak and dreary,” Sensei said without any particular distaste.

“The moon is out tonight.” A hazy half-moon hung high in the sky.

Sensei took one of the rice crackers and tilted his teacup as he refilled it with saké. “My wife was the kind of person who didn’t think things through.”

“I see.”

“She just loved the things she loved, and hated the things she hated.”

"Strange Weather in Tokyo" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Strange Weather in Tokyo". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Strange Weather in Tokyo" друзьям в соцсетях.