“A love fated in the stars.” As I sat there, watching the happy couple seated on the wedding platform and listening to the toast, I remember thinking to myself there wasn’t a chance in a million that I would ever encounter “a love fated in the stars.”

I had a craving for an apple so I took one from the basket. I tried to peel it the way my mother did. Partway around, the skin broke off. I suddenly burst into tears, which took me by surprise. I was cutting an apple, not chopping onions—why should there be tears? I kept crying in between bites of the apple. The crisp sound of my chewing alternated with the plink, plink of my tears as they fell into the stainless steel sink. Standing there, I busied myself with eating and crying.

I PUT ON a heavy coat and left the apartment. I’d had this coat for years. Deep green, worn, and fuzzy, it was still a very warm coat. I always felt colder than usual after a crying jag. I’d finished my apple and had enough of sitting in my apartment, shivering. I put on a loose-fitting red sweater, which I’d also had for years, over brown wool pants. I changed into bulky socks, slid on thick-soled sneakers and, lastly, gloves, and went out the door.

The three stars of Orion’s belt were clearly visible in the sky. I walked straight ahead. I tried to maintain a brisk pace, and I started to warm up after I’d walked for a while. A dog barked at me from somewhere, and instantly I burst into tears. I would soon turn forty, yet here I was acting like a little girl. I kept walking, swinging my arms like a child. When I came across an empty can, I kicked it. I grabbed and pulled at the tall, withered grass on the side of the street. Several people on bicycles rushed past me, coming from the station. One of them didn’t have his light on, and when we almost collided, he yelled at me. Tears welled up anew. I had the urge to sit down right there and sob, but it was too cold for that.

I had completely regressed. I stood in front of a bus stop. After waiting ten minutes, there was still no bus. I checked the bus schedule and saw that the last bus had already come and gone. I felt even more lonesome. I stamped my feet. I could not get warm. A grown woman would know how to get warm in a situation like this. But, for the moment, I was a child and helpless.

I decided to head toward the station. The familiar streets seemed alienating somehow. I felt just like a child who had tarried on her way, and now it was dark out and the streets that led back home seemed unrecognizable.

Sensei, I whispered. Sensei, I can’t find my way home.

But Sensei wasn’t here. I wondered where he was, on a night like this. It made me realize that I had never called Sensei on the telephone. We always met by chance, then we’d happen to go for a walk together. Or I would show up at his house, and we’d end up drinking together. Sometimes a month would go by without seeing or speaking to each other. In the past, if I didn’t hear from a boyfriend or if we didn’t have a date for a month, I’d be seized with worry. I’d wonder if, during that time, he’d completely vanished from my life, or become a stranger to me.

Sensei and I didn’t see each other very often. It stands to reason, since we weren’t a couple. Yet even when we were apart, Sensei never seemed far away. Sensei would always be Sensei. On a night like this, I knew he was out there somewhere.

Feeling more and more forlorn, I began to sing. I started out with “How lovely, spring has come to the Sumida River,” but it was completely out of keeping with the cold night. I racked my brain for a winter song but couldn’t call any to mind. At last I remembered “The silver-white mountains, bathed in morning light,” a ski song. It didn’t quite fit my mood but I didn’t have much choice since I couldn’t come up with any other winter songs, and I went on singing.

Is it snow or is it mist, fluttering in the air,

Oh, as I rush down the hill, down the hill.

I remembered the words clearly. Not just the first verse but the second verse as well. I was surprised that I could resurrect such lines as “Oh what fun, bounding with such skill.” I was feeling a little better so I moved on to the third verse, but no matter how I tried, the last part would not come back to me. I could remember “The trees above and the white snow beneath” but not the last four bars.

I stopped and stood there in the darkness, trying to think. Every so often someone would walk by from the direction of the station. They avoided me as I stood rooted to the spot. And when I started singing snatches of the third verse under my breath, they gave me an even wider berth.

Still unable to remember the last words, I felt like crying again. My feet started walking of their own accord as my tears started flowing on their own as well. Tsukiko. I heard my name but didn’t turn around. I figured it must have been in my head. After all, Sensei wouldn’t very well just appear here.

Tsukiko. I heard someone call my name again.

I turned around this time, only to see Sensei standing there with his perfect posture. He was wearing a lightweight but warm-looking coat and carrying his briefcase, as always.

Sensei, what are you doing here?

Taking a walk. It’s a lovely evening.

Just to be sure that it really was Sensei, I surreptitiously pinched the back of my hand. It hurt. This was the first time in my life that I realized people actually did such a thing—pinched themselves to make sure they weren’t dreaming.

Sensei, I called out. He was a little ways away from me, so I called out softly.

Tsukiko, he replied, enunciating my name.

We stood there for a moment, facing each other in the darkness, and I no longer felt like crying. Which was a relief, since I had started to worry that my tears would never stop. And I didn’t even want to imagine what Sensei might say to me if he saw me crying.

Tsukiko, the last verse, it’s “Oh, the mountain calls to me,” Sensei said.

What?

The words to the ski song. I used to ski a bit myself back in the day.

Sensei and I began walking side by side. We headed toward the station. Satoru’s bar is closed on holidays, I said.

Sensei nodded, still facing forward. It would be good for us to go somewhere else for a change. Tsukiko. I just realized this will be our first drink together this year. That’s right—happy new year, Tsukiko.

Next to Satoru’s place was another bar with a red paper lantern hanging out front. We went in and sat down with our coats still on. We ordered draft beer and drained our glasses in one gulp. Tsukiko, you remind me of something, Sensei said after his first quaff. What is it…? Hmm, it’s on the tip of my tongue.

I ordered yudofu and Sensei ordered yellowtail teriyaki. A-ha, I’ve got it! With your green coat, red sweater, and brown pants, you look like a Christmas tree! Sensei said in a slightly high-pitched voice.

But it’s already New Year’s, I replied.

Did you spend Christmas with your boyfriend, Tsukiko? Sensei asked.

I did not.

Do you have a boyfriend, Tsukiko?

Yeah, I’ve got one or two, or ten boyfriends, even.

I see, I see.

We soon switched to saké. I picked up the bottle of hot saké and filled Sensei’s cup. I felt a sudden rush of warmth in my body, and felt the tears well up once again. But I didn’t cry. It’s always better to drink than to cry. Sensei, happy new year. I wish you all the best in the coming year, I said in one breath.

Sensei laughed. Tsukiko, what a lovely greeting. Well done! Sensei patted me on the head as he complimented me. With his hand still on my head, I took a long sip of saké.

Karma

I UNEXPECTEDLY RAN into Sensei as I was walking along the street.

I had been lazing about in bed until past noon. Work had been extremely busy for the past month. It was always close to midnight by the time I got home. For days on end, I would hastily scrub my face before falling into bed, without bothering with my nighttime bath. Even on weekends, I almost always went in to the office. I had been eating terribly and, as a result, I looked drawn and haggard. I’m a bit of a gourmand, so when I’m not able to take the time to indulge my tastes as I please, I begin to lose a certain vitality, as was reflected in my pallid complexion.

Then at last on Friday—yesterday—I had successfully gotten through a major portion of the work. For the first time in what felt like ages, I slept in on Saturday morning. After having a good lie-in, I ran a hot bath, right to the brim, and took a magazine in with me. I washed my hair and immersed myself countless times in the hot water, into which I had trickled a wonderfully scented potion, occasionally stepping out to cool off, all the while perusing about halfway through the magazine. I must have spent nearly two hours in the bathroom.

I drained the water from the bath and quickly scrubbed the tub, and then I pranced about my apartment, naked except for a towel twisted atop my head. It was one of those moments when I think to myself, I’m glad to be alone. I opened the refrigerator and took out a bottle of mineral water, poured half of it into a glass, and gulped it down. It made me think about how I had hated mineral water when I was younger. In my twenties, I had traveled to France with a girlfriend of mine, and we had gone into a café to get something to drink. I just wanted plain, regular water, but when I ordered “Water,” they brought out mineral water. I was so parched and hoping to quench my thirst, but the moment I swallowed it down, I choked and nearly threw up. Yet I was so thirsty. And here was water, right in front of me. Yet this water—with bubbles springing up from the carbonation—was a bitter mouthful. Even had I wanted to drink it, my throat would have rejected it. But since I didn’t know enough French to say, “I would prefer still water rather than water with gas,” I forced my friend to share with me the lemonade that she had ordered. It was terribly sweet—awful, really. That was before I was in the habit of slaking my thirst with beer instead of water.

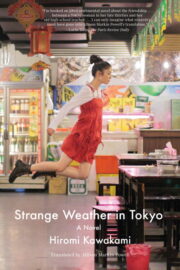

"Strange Weather in Tokyo" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Strange Weather in Tokyo". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Strange Weather in Tokyo" друзьям в соцсетях.