“So what are we going to do now?”

“I have made the arrangements. Her body is already in the funeral home. The service will be held in two days and I, or one of my staff, will come pick you up and drive you there. It was her wish to be cremated and that her ashes be scattered in Bohai together with Wang Jin’s.”

“But my father was buried in a cemetery—you just took me there!”

“Your mother placed your father’s ashes in three different places: the grave, under the ruined town city wall, and in her prison cell.”

I was not listening. Too overwhelmed by the news, my mind began to drift to the brief, now infinitely precious meetings I’d spent with my mother.

“Miss Lin”—he studied me with concern—“you all right? Can you come to my office now to go over the arrangements? If not, you’d better get some rest and we’ll do it later.”

“Maybe later. Sorry, my mind is not working right now.”

“I understand. I will call you tomorrow. Rest today.”

Back in my room, I threw myself onto the bed and cried my eyes out. If there really was a God, why did He bring my mother back to me, only to take her away to orphan me a second time?

God was my Hong Kong mother’s adviser-savior, but He seemed to have no answers to my questions, which just bounced back at me like squash balls, making noise but carrying no message. Maybe the blind fortune-teller, Soaring Crane, was a better consultant—at least he listened and responded. Now I wondered if my mother Cai Mayfong’s Christian devotion was due to her secret guilt for the unforgivable sin of betraying her sister. I asked, but God kept His opinion, if He had one, to Himself.

The next days passed as a blur—meeting with Lo, reading my mother’s will, visiting the funeral home. When I arrived for the service, the director offered me a coarse, white funeral costume to wear, but I declined. Hand torn—instead of scissor-cut—and made of coarse hemp, the garment is to show that the grief of the descendents is too great for them to pay attention to what they wear.

My pale green silk dress was met with strong objections from Lo.

“You have to wear white to show respect for the deceased!”

“You want to make me even more depressed so that I follow my mother into the grave?”

Since as a daughter I was indispensable to the service, finally he had to back down.

But then my depression deepened when I saw that only two people had come to bid my mother farewell.

Before I had a chance to ask Lo, he told me, “Miss Madison had many visitors in the beginning, but as the years passed and they realized there was no hope of her release, they stopped coming.”

I exclaimed, “That’s terrible!”

“You must have heard of the saying, ‘A prolonged disease will keep even the most filial son away’?” He shrugged. “Human nature.”

I nodded. What more could I say? “Then who are those two people over there, her best friends?” Or her lovers, I thought as I pointed to the two men talking to each other in a far corner.

“Oh, no, they’re just staff here.”

Because, except for Lo and me, there were no guests to shake hands, to bow or prostrate to the deceased’s picture, or to utter comforting yet empty words, the whole service was over in a mere half hour. I carried out my duties of burning paper offerings, kneeling in front of my mother’s portrait and kowtowing three times while hitting my head hard enough on the floor to be heard by her departing soul. Finally I pressed the button to start the combustion of her physical remains. I tried hard to hold back my tears as my mother, or my aunt, or Mindy Madison, or Cai Mindi, was transformed from flesh to ashes.

Two days later, a car was arranged by Mr. Lo to drive us to Tianjin, a city southeast of Beijing; after that, a small boat took us out on the Bohai Sea. Steadying myself on the undulating boat, I tightly clutched the cindered remains of my two newly discovered parents.

Everything floated around me as if in a dream. I was holding my parents as my mother had me when I was a baby. Poor Wang Jin, he didn’t even know, as he drew his last breath, that he had left a child on earth.

The soothing breeze and the brilliant cerulean of the ocean contrasted with my somber mood. On the jars were pictures of my parents in their prime. My mother’s hair was braided into two thick pigtails, her face tilted, her eyes looking up at something outside the picture, as if aspiring to a future filled with hope and adventure. The smile blooming on her smooth face made it seem as if spring was peeking around the corner.

My father had a crew cut, and his intense eyes appeared larger through the lenses of his round, metal-rimmed glasses. His tight jaw and penetrating gaze gave him the air of a poet or a revolutionary. He seemed filled with ideals and passions to rebuild his country, or, if necessary, to sacrifice his young life for it. Two young people, partners and soul mates, filled with energy, life, and hope for the future. Had they imagined a home full of children, followed by a comfortable old age surrounded by grandchildren clinging to their stiff knees or climbing on their laps to mess with their snow white hair?

I felt despondent. Who could imagine having to bury her parents a second time?

I lost track of the time until I realized that the boat had slowed and was now bobbing in the waves.

The captain, a fiftyish, rod-thin man, yelled to Lo, “Is this far enough?”

“Yes, please wait here for a few minutes.”

“Are we far from the shore?” I asked.

Lo said, “Now you can carry out your last duty as a filial daughter.”

Feeling numbed, I didn’t respond.

“You can say a private prayer first if you want. I brought the Heart Sutra, so you can also read it to send your parents to the Western paradise.”

This stern-faced man in front of me was definitely a man of many details.

“I’ll first read the Heart Sutra for my parents, then I’ll also pray to God.”

“Go ahead.” He held out the sutra.

I looked up at the blue sky to meditate for a few seconds, remembering the Chinese philosopher Laozi’s saying that heaven is indifferent, treating all beings like straw dogs. True, we were insignificant as a speck of grain in heaven, or in God’s eye. Just like my parents, who had turned from flesh into ashes and were now to be dispersed in the infinite nothingness.

I lowered my head to read the printed Buddhist wisdom:

The Bodhisattva of Observing Ease is walking deeply in the profound wisdom, reflecting that all five skandhas are emptiness while transcending all sufferings…

The ancient sutra was too abstruse for my Westernized mind to comprehend. However, I did like the phrase “transcending all sufferings.” Who wouldn’t want that? After I finished reading, I also muttered a short prayer to God: “Dear Lord, I am here to scatter my parents’ ashes into the sea. I thank Mr. Lo and the captain for taking me here so I can give my parents a proper sea burial. I hope both my parents, whatever their sins, will soon be in Your arms hearing the angels sing. I also look forward to the day when I could reunite with them in Your loving embrace. Thank You, Lord, Amen.”

Too exhausted to think after the prayer, I turned to Lo for further instruction.

He said, “Now you must say your final good-bye and scatter their ashes into the sea.”

I lifted my mother’s jar first and kissed her two cheeks on the picture. “Ma, have a good journey home.” I thought that was the most appropriate thing to say, since she’d been such a fearless adventurer. Then the desert, now the sea, then heaven, or the Western Paradise, depending on which would be the most challenging route for her.

Since I didn’t really know Wang Jin, I only kissed his forehead. Staring at me with his longing eyes, my stranger father seemed to say, “Daughter, sorry that I never had the chance to hold you in my arms when you were little, or to lean on you for comfort in my old age. Fate had it that we missed each other’s presence. The Chinese call this cajian erguo, swiftly rubbing against each other’s shoulders in a huge crowd.

“Since we are not able to look after you, you must take care of yourself, my dearest daughter. Get married and have many little ones and think of me seeing my grandchildren’s sweet smiles and hearing their joyous laughter from above. I wish you a very happy, long, and healthy life. Now good luck and good-bye.”

I was jolted by Lo’s touch on my shoulder. He handed me his handkerchief. It was then that I realized my face was raining tears.

Lo pointed at my mother’s jar. “It is time to put Miss Madison to rest in the sea.”

I noticed that his eyes were red and his voice trembling. Was it possible that he was crying, as he did when he had broken the news of my mother’s death in the hotel? Could it be that a lawyer would cry for his client? Or was it a man crying for a woman?

“Mr. Lo, are you OK?”

His voice was barely audible. “I’m fine. It’s just the salt spray gets into my eyes.”

I stared at him for a moment before I turned to face the sea, open the jar, and spill its resident into the water. The sea appeared so calm and so bright, and so oblivious of our sufferings on earth. My mother’s ashes pirouetted in the air like dancing stardust before dipping to kiss the waves.

Next I opened Wang Jin’s jar and did the same. Strangely, his ashes fell straight into the sea without lingering in midair. Maybe because he couldn’t wait to join his most beloved woman so she wouldn’t feel alone on her journey of no return.

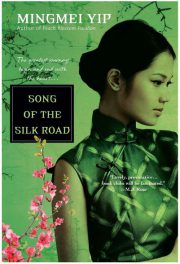

"Song of the Silk Road" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Song of the Silk Road". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Song of the Silk Road" друзьям в соцсетях.