Before lunch was served, an air hostess handed out Chinese newspapers, and I took one. As I was flipping through pages of coverage of banal events and steamy gossip, a headline caught my attention.

Five men—art thieves and traitors—were executed in Beijing yesterday.

All five belonged to a criminal organization, believed to be run by a black society, which steals national treasures from museums and smuggles them to sell to rich capitalist collectors in the U.S. and Europe.

The government promised to intensify its efforts to catch art thieves and will continue to deal with them harshly. Police will soon arrest several accomplices, “fishes who slipped through holes in the net….”

The government also plans to send officials to the U.S. and Europe to demand the immediate return of the stolen objects….

I had been feeling excited about my trip, but this reminder of harsh Chinese justice made me uneasy. I put away the newspaper and dozed fitfully until finally awakened by the welcome announcement, “Flight attendants, please prepare for landing….” Weary from the long, cramped flight, I rubbed my eyes, hoping I would be tough enough for the adventure ahead.

In Beijing, I settled into a small hotel near the Temple of Heaven. After taking a not-so-hot bath, I devoured a truly hot and spicy beef noodle soup at the hotel’s restaurant, then went back to my room, forcing myself to stay awake to reread the instructions for the first part of my trip. My first stop would be Xian, the starting point of the Silk Road as well as the burial place of the famous terracotta warriors who had been uncomplainingly guarding China’s first emperor’s grave for more than two thousand years. The thought of finally seeing this famous sight excited me, but before I could leave Beijing I had to visit Lo and Wong Associates for final instructions.

I called the law firm to make an appointment, then took a taxi directly to the firm, situated in the Wangfu Jing commercial district. After entering the relatively big and clean office, I gave my name to the young receptionist and was quickly led to the office of the lawyer handling my case. Mr. Lo, a small man, struck me as a person soaked in the sea of sadness. Suffering was written all over his fiftyish, elongated, bespectacled face. Lines on his forehead and around his eyes looked like calligraphic strokes of poems expressing unrequited love, separation, even death. The sole decorations in his office were a few diplomas and a couplet in Chinese calligraphy on the wall:

One cannot possibly please everybody

But one should never betray his own conscience.

Did that mean he was a good lawyer? Or a bad one displaying this popular saying to cover up?

After having shaken hands and exchanged pleasantries like, “How was your trip?” “Fine, thank you.” “Have you eaten?” “Yes, I’ve just had lunch, thanks.” “Hope you enjoy Beijing.” “I definitely will,” and the like, we plunged into serious business.

Lo, after reviewing what I’d already been told at Mills and Mann back in New York, handed me my aunt’s complete itinerary documenting all the routes and what I needed to do at each stop.

I signed some documents, then asked the sad mask across from me, “Mr. Lo, when will I meet my aunt?”

His answer, delivered in a dry tone, came as a surprise. “Miss Lin, you will not meet her until you finish your trip and come back here to collect the money.”

“But why can’t I meet my aunt before I go? I didn’t even know I had an aunt.”

My suspicions arose afresh. Had I gone this far simply to be scammed? But why would someone pay so much money in advance just to cheat later? After all, I had nothing to be cheated out of.

Lo’s low-wattage voice again expanded into the legal air. “This is your aunt’s decision. You can find out when you see her after your trip.” He pushed up his black-rimmed glasses, then studied me through the thick lenses. “Now, pay attention. There are documents in different envelopes to prepare you for every assignment. You must read them very carefully and follow the instructions completely. They are all numbered, so open and read them accordingly. Do not open any envelopes ahead of time.

“You can explore and do other things on the trip, as long as you complete the journey in no more than eight months.” Now his small eyes began to drill into mine. “Remember, don’t try any tricks. If you do, you’ll be the one who’ll suffer the consequences. You understand?”

I nodded. This all sounded even more alarming than I’d expected. I wasn’t quite sure what the “tricks” might be or the apparently dire consequences.

“Any more questions?”

I shook my head.

I left the office with my document-laden backpack crushing my back. My enthusiasm for sightseeing had evaporated as a result of Lo’s ominous words. I decided not to explore the city but went straight back to my hotel to eat, take a shower, then go to bed.

The next day in the afternoon, after a two-hour plane ride from Beijing, I arrived at the airport for Xian, the city of Western Peace. Walking out of the terminal building dragging my heavy suitcase, I was surrounded by a crowd of shouting, pushing, smoking, spitting, luggage-hauling, yelling-at-children Chinese. After struggling through the melee, I finally boarded a taxi. During the ride to the small hotel that I’d booked, my weary eyes tried to absorb the bustle of the exotic city until I finally saw the majestic Ming dynasty bell tower in the midst of noisy traffic circling around it. I imagined the bell ringing to welcome me as it would have the emperor six hundred years ago.

The hotel room was small but not too dirty. I was elated to see a bathroom, meaning I didn’t have to use a communal one, which was usually rank, not to mention risk my much-coveted naked body being visually and mentally molested by Chinese Peeping Toms.

I took a quick shower, ate a pork and pickled vegetable noodle soup at the hotel restaurant, then hurried back to my room. Sitting on the narrow bed, I set out my guidebooks, my new notebook, and my aunt’s documents, and plunged into work.

In Xian I was to visit the terracotta warriors and scrape a tiny piece of clay from one of them—and it had to be soldier number ten. After that, I’d go to the Beilin Museum, locate the Classic of Filial Piety stele, and study its inscription. The first requirement seemed pretty weird, and the second, pointless. However, to study the inscription should be relatively easy in comparison to scraping a piece of clay from the famous warriors. That was downright scary. Would I be arrested and put in jail—or worse?

As I was perusing my instructions, a small row of characters caught my eyes:

This is not vandalism but protecting China from corruption. Soldier number ten is a fake. Further instruction will tell you what to do with the piece of clay.

The next morning, a long taxi ride brought me to my rendezvous with the warriors who had aged not at all while waiting for me for two thousand years. I arrived fifteen minutes before the museum’s opening time, hoping I’d be among the first few to be let in and that the place would be relatively empty and supervision relaxed. By the entrance only five people were waiting: an elderly Chinese couple, two Chinese girls talking about something, and a young man with a thick, curly mop of chestnut hair. I studied them as subtly as I could. All seemed harmless, except maybe the foreigner, who kept looking at me and making me uneasy. I opened my guidebook and feigned reading.

After a brief wait under the morning sun, two uniformed guards, one young and the other middle-aged with a cigarette dangling between his lips, opened the gate and let us in. The huge mausoleum welcomed me with the chill of its two-thousand-year-old air. I tightened my sweater around my chest.

Even though I’d seen many pictures of the terracotta warriors, the sight of the more than one thousand life-sized figures standing in their shallow pits was stunning. There they stood, row after row, each with his own facial expression, armor, headgear, and weapon, striking the same heroic poses for over two thousand years. Intense qi, energy, emanated from these handsome young men looking so alive yet so still, forcing a gasp from my lips.

A male voice rose next to me, asking in English, “You want my jacket?”

I turned. The very young foreigner was about to take off his coat.

“Oh, no, thanks. I’m fine,” I said, then turned right back to study the formidable military formation.

A few moments passed and the same voice rose again in the chilly air. “You’re a tourist?”

I turned to study the stranger. What struck me was, again, his thicket of chestnut hair—which made me think of wood shavings curling under a plane—and his smooth, delicately featured face. “Yes, how do you know?”

He laughed a little. “Because you read your guidebook in English.”

“Oh.” I silently cursed. No matter how careful you think you are, there are still things that can unexpectedly give you away.

He asked, “Where you from?”

I hesitated.

An awkward silence, then he said, “I’m from New York City.”

“Me too, what a coincidence!” I exclaimed, then hated the enthusiasm in my voice.

Even though I knew nothing about this stranger, meeting a fellow New Yorker made it all seem less unreal. The Chinese say there are four great happinesses in the world:

Pouring rain after a long drought

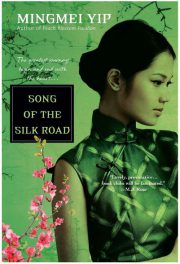

"Song of the Silk Road" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Song of the Silk Road". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Song of the Silk Road" друзьям в соцсетях.