Thinking this, I blurted out, “No way!”

“Lily, isn’t that what you want?”

“Oh, I’m sorry, Chris, that’s not what I mean.”

“Then what do you mean?”

“I… am not feeling very well. I need to rest for the day. I’ll call you tomorrow.” Before he had a chance to respond, I hung up, then disconnected the phone.

That evening, I ordered a spring roll, hot and sour soup, kung pao chicken, beef broccoli, shrimp dumplings, scallion pancake, and fried banana from My Place Shanghai Tea Garden, my favorite expensive Chinese restaurant—a rival of Shun Lee Palace. Of course I couldn’t possibly finish all this. I just wanted to savor the pleasure of watching the food fill up the table. Delicious smelling abundance always made me feel good—happy, warm, fulfilled, pampered, and now rich.

To celebrate the occasion, I put on makeup and a revealing little black dress. While waiting for the delivery, I paced around my studio, feeling a sudden wave of affection for my modest belongings in this tiny refuge on Earth: the celadon vase spilling Chinese good-luck bamboo plants, framed posters of Van Gogh’s starry sky, and a Monet landscape opening vistas in the otherwise dull white walls. My books were stuffed in milk crates that I had painted in bright yellow, red, and green, not only novels but works on some of my favorite subjects: goddesses, feng shui, energy healing, even combing your hair 108 times for health and longevity.

After my parents’ death, I had thrown away practically all their possessions, which were not many. I kept all the photographs, which were not many, either, since my father, a businessman with more than one wife, seldom came home, and my mother, who worked almost her entire life at a church, never went out for fun. I had also kept my parents’ letters, my father’s childlike calligraphy ren (till he’d strike it real big, he’d always assured us), my mother’s wedding gifts—silk scarf, jade earrings, embroidered Chinese dresses—and a few other odds and ends. Wrapped in Mother’s silk scarf, these few possessions accompanied me on the journey of eight thousand miles from Hong Kong to New York City, the place I now called home.

When I heard the delightful ding-dong! I dashed to open the door and took the food from the deliveryman. I tipped him generously to match my mood, then set out the food on the table. At the center I placed the vase overflowing with my favorite white roses and baby tears. Then I lit two candles, put on my favorite music, opened a bottle of red wine, and poured myself a full glass. I meditated on the sloshing ruby liquid, then raised my glass to the moon outside the window. To myself, I recited the Song dynasty poet Su Dongpo’s famous lines:

Among clusters of flowers, I hold a jar of wine.

To drink all by myself,

I invite the moon to join me.

Adding my shadow, there is a party of three…

When drunk, we couple; when awake,

we go our separate ways…

The last line made me think of my relationship with Chris. When drunk we coupled; when awake, he went back to his wife and kid and I to my would-be-great-Asian-American novel in progress, which I’d been writing since the first day I enrolled in the creative writing program at NYU.

“Hai…” I let out a long exhalation, toasted to the moon, then invited the disc to join me for my sumptuous dinner. Just when I was happily devouring my kung pao chicken and gulping down my soup while listening to Ray Charles’s “What’d I Say” on fucking disguised as dancing, the doorbell rang. The ringing sounded desperate, like the scream of a child who’d just lost sight of his parents.

Damn! It must be the super, who lived one floor above and had a crush on me. Since I’d told him about the trip he had found new excuses to talk to me.

I threw down my chopsticks, dabbed my chicken-greased-cum-lipstick-smeared lips, hurried to the door, and swung it open.

To my surprise, it was not my super, but Chris. In his one hand was a bunch of white roses and baby tears, and in his other hand a big plastic bag. His hair was tousled, and there were dark circles under his eyes like those of a panda’s. My uninvited guest was slowly giving me a bitter once-over.

“You’re not going to invite me in?”

“Yes. Of course.”

After closing the door, we went to the dining area, where Chris immediately spotted the feast. He dumped the big bag and the flowers on the galley kitchen counter. “Lily, you told me you’re sick so I brought you roses and baby tears and your favorite dishes—kung pao chicken, beef broccoli, shrimp dumplings, scallion pancake, hot and sour soup, and fried banana from your favorite, My Place Shanghai Tea Garden. So, what’re all these flowers and food about”—he tilted his head toward the boom box—“and the fucking Ray Charles? You expecting someone to fuck?”

“Chris! Watch your French!”

“Then answer me in plain English! Why are there so many dishes?!”

“Hmm… I thought maybe you’d come.”

“Come? Only if I’ll get a good fuck. Will I get one tonight?”

Not funny, the double entendre. I remained silent.

He spoke again, his tone softened a bit. “But my girlfriend is Chinese, people who love to eat, so I’ll always bring food. Besides, why didn’t you answer the phone? I’ve called and left five messages. Then I got panicky, thought maybe you were hurt or something.”

“I’m so sorry, Chris.”

“If someone is coming, then I’ll leave right now.”

“Please, Chris, no one’s coming. Please just sit down and eat with me.” I kissed him on the lips, but they were sealed like a miser’s safe.

We sat down.

“Lily, I want an explanation.”

“About what?”

He gestured to the table. “Why are you having such a big feast?” Then he motioned to my exposed half moons. “And this dress. Are you celebrating something, with someone, instead of with me?”

“Of course not.” I shot him a flirtatious smile, then pulled him into my arms and kissed him. “Please, Chris, you must be tired and starving, so let’s eat, and then we’ll fuck our brains out if you like.”

“All right,” he said, his eyes giving out a few faint sparkles, finally.

The meal was consumed almost in total silence, except for an occasional smacking of lips, slurping of soup, clicking of chopsticks, and sighs from Chris’s mouth.

After we finished and Chris cleaned and put away the dishes, I put my arms around his neck, pressed my body hard against his, and put up my most seductive smile, like a mistress’s. “Honey, let’s go to bed now.”

He followed me like an obedient dog—just as I’d expected.

3

Ghost Warriors and the Imperial Bath

The following Wednesday, the day before I left for China, Chris and I had another quarrel. However, canceling the trip just to indulge a man whose marital bed was occupied by another was out of the question—unless I was a complete fool.

And so on a Thursday morning in May, despite a dull headache and a pounding heart, I found myself lugging my heavy bags down my four flights of stairs, then hailing a taxi to JFK Airport. It was hard for me to believe I was finally going to China, to the Silk Road, the desert, all by myself. However, as the airport finally came into sight, fear seized my body. Would I return from the ancient route for trading silk—or vanish into its silky thin air?

During the long plane ride, I occupied myself studying my guidebooks on the different remote cities along the Silk Road: Xian, Jiuquan, Xinjiang, Dunhuang. I closed my eyes, imagining their names’ associations:

Xian—Peace in the West. This was the city’s present name, but during the Tang dynasty one thousand years ago this same city had the grander name of Changan—Eternal Peace. Would I find peace in this ancient city? I hoped it would not be eternal peace—my death.

Jiuquan—Wine River. What kind of wine? White, red, blush, Californian, French, Australian, Chinese… Would I get drunk there?

Xinjiang—New Frontier. Two years ago when I’d arrived from Hong Kong, New York had been my new frontier. I wondered what awaited me on this one.

Dunhuang—Blazing Beacon. Could I trust it to guide me?

The first city I had to visit was Xian, the gateway to the Silk Road. I reviewed in my mind what I had read about this first capital of the Chinese empire. Founded by the first emperor of China, by the second century BC, the western gate of this old capital had become the terminus for caravans from India, Persia, and Central Asia. The “Barbarians” brought glass, gold, silver, spices, gems, fabrics, and exotic animals such as ostriches to the Middle Kingdom, then returned with silk, tea leaves, jade, bronze, ceramics, lacquer, chrysanthemums, apricots, peaches, even peacocks.

Among all this merchandise, silk was most treasured. This lustrous, delicate, and water-soft material was so coveted by the rich and powerful that it was used as currency, its value equivalent to gold. Before paper was invented, it was on silk that early Chinese scribes brushed some of their most precious classics.

Xian was at its peak of prosperity during the Tang dynasty more than a thousand years ago. With two million inhabitants, the city was like a tasty soup cooked with myriad spices and herbs, a cultural cauldron of races and nationalities—Arabs, Persians, Central Asians, Indians, Tibetans, even Byzantines.

It was to Xian that one of the most famous travelers in all of Chinese history, the Buddhist monk Xuanzhuang, returned from his legendary “Journey to the West,” that is, India, bringing with him hundreds of Buddhist manuscripts. As he entered the city gate, the monk was welcomed with incense, prayers, drums, and chanting by cheering and crying devotees….

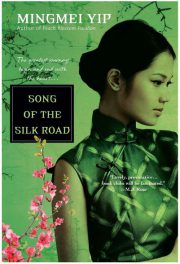

"Song of the Silk Road" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Song of the Silk Road". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Song of the Silk Road" друзьям в соцсетях.