That night I had a dream. Lop Nor, his son, and I were a family. We lived near the cool Crescent Moon Lake and made our living by selling tourist souvenirs. One night when his son was asleep, we tiptoed outside our house and headed toward the shimmering lake, where we took off our clothes and plunged in. We frolicked, splashed water at each other, and laughed like children, then we made love. The moon and its silvery sprinkles were everywhere—the sky, the lake, our happy faces, our naked bodies.

When Lop Nor kissed me, he murmured, “My love, I’m kissing the moon.”

After passionate love, Lop Nor dived under the lake. I was waiting for him to call me to join him to make love again on the lake’s bottom. But alas, he never emerged. I screamed, but my voice was lost amidst the intense moonlight and the glittering stars….

I awakened to the sound of my own scream. For long moments, the burning images of the dream lingered before finally fading. I was both sad and happy that it was but a dream. Sad that the sex was only imaginary and Lop Nor was no longer in this life, but happy that Alex was. And sad that on his last day in Urumqi, Alex and I had quarreled and that he’d left angry and hurt. Would we cross paths again on this Ten Thousand Miles of Red Dust? As lovers, or just as friends?

I lifted Lop Nor’s pendant from my neck and pressed my burning lips to its cold surface. I realized that since I had no intention of being an herbalist, the best I could do with the precious herbs I’d been bequeathed was to pass them on to someone who could make use of them.

However, as much as I would never forget Lop Nor, I needed to move on with my own life. Thus decided, I felt a huge stone lifted from my chest.

17

Turpan Museum

The next day I awoke before dawn, swallowed a bun, and downed the leftover tea. Then I put the scroll and the Buddha into my backpack and set out. Though I wanted to make one last trip to the Black Dragon Pond to pay my final respects to Lop Nor, I decided I could not take the risk. It was all too possible that Floating Cloud and Pure Wisdom would soon discover my theft and come after me. Lop Nor was already dead, and nothing I could do would bring him back to life. Sad to say, since the dead cannot move on the earth, the living must move on. I was nervous carrying the two treasures: The sooner they were back safe in the museum, the better.

I went to Urumqi first, and from there took a tedious bus ride on the new highway to the city of Turpan, once an important oasis city during the Silk Road days. At the dusty bus stop, there were no taxis, but a broken-down car slowed in front of me and I struck a bargain with the driver to take me to the Turpan Guest House for a few yuan. I checked into the dingy room, took a quick shower in the hotel’s communal bathroom, then went to sit on the sagging bed where I spread out all my papers, books, and maps to plan.

The next move would not be easy. I needed to wait patiently for the right moment to exchange the reproductions in the Turpan Museum with the two pieces I had taken from Floating Cloud’s temple. I scribbled down all possible options, deleting the most impractical, leaving:

1. Bribe the museum director.

2. Seduce him.

3. Buy him a big dinner, get him drunk, then take his key.

I quickly crossed out the second one. After Floating Cloud, I had no appetite for sex with another man, monk or not. I didn’t like the fact that the thought had even entered my mind in the first place. Uninhibited in love though I might be, I was not an all-accommodating split-slit slut!

Given the expectation that the drunken dinner might create, this left only the first option. But—what if the director refused a bribe and instead reported me to the police? Other questions leaped into my mind like monkeys cavorting on shaky branches: How could I get rid of the guards and visitors so I could do my job? How would I steal the keys from the guard, or the museum director, or whomever, to open the display window? And how would I know which key was the right one? If I failed to get the key, could I break open the vitrines without setting off the alarm?

After these agonizing ponderings, it occurred to me that museum security was probably not very tight in such a remote place as Turpan. From the Silk Road books I’d read, the Chinese are quite casual about their own treasures—unless someone else wants them. After all, explorers like Aurel Stein and Paul Pelliot walked away with thousands of manuscripts and art from Dunhuang with nary a peep from the Chinese. Only when these works became famous in Europe did the Chinese raise an outcry and condemn the explorers as bandits. Now anyone caught trafficking in such objects was quickly shot. So my only hope was that the Turpan Museum was still as relaxed about art treasures as in Stein and Pelliot’s time.

After more racking and tweaking of my mind, I still couldn’t think of a good plan, let alone a perfect one. So I decided to take a look at the museum first. If security was lax, I’d sneak in, find a way to open the display window, and exchange the objects. Worst case, I’d befriend the curator, or, as the last resort, seduce him.

Then I sighed, thinking of my young lover. Alex, sorry that we fought on our last day together. I hope you understand that my calling in life is different from yours. You want a family, and all I want is freedom, including the freedom to love. I don’t want to be like my mother, imprisoned by one man, one love, one life.

The next day, under the scorching sun, I climbed into a taxi that looked almost as old as the city itself and asked the driver for the Turpan Museum. It seemed a good sign that he had to ask directions from another driver—most likely the museum was not as careful as those that attracted crowds in the major cities. As we drove through the desert, I watched the endless stretch of blue sky, brown sand, and yellow cliffs. I lifted my camera to capture the intricate formations sculpted over the millennia by the invisible hands of wind and rain. As I snapped away, I felt a tinge of regret at not having the leisure to explore this peculiar land.

So when the young driver looked at me in the rearview mirror and asked, “Where you from?” I shrugged to discourage the unwanted conversation.

The museum was even smaller than I’d expected. It looked more like a private house with a few rooms of personal items accumulated over a few years. At the Metropolitan in New York, the entire collection would barely fill the smallest room. I walked to the reception desk where a sloppily uniformed and plain-looking middle-aged woman was gulping ravenously from a plastic bowl.

I cleared my throat. “Good morning. How much for one ticket?”

Cheeks bulging as she chewed, she answered without looking up. “Five.”

I handed over a five renminbi.

Again, she didn’t bother to look up at me as she handed me the ticket, her other hand tightly clutching her bowl of roast lamb over rice like a child her favorite toy.

“Thank you.”

“Don’t take pictures or touch anything.” She gave me an annoyed look, her voice harsh and raspy.

After that, she went back to devoting all her energy to devouring her food. Her cheeks continued to masticate, her chopsticks tapping hard on the inside of her bowl with merciless determination. The food was steaming and she wanted to give it her total attention before it got cold. I appreciated her engagement with her food, while being extremely grateful for her carelessness. Both the food and her appetite for it started my saliva flooding my mouth; I swallowed it in one big gulp.

Once inside the dingy museum, I wandered around the different rooms and was surprised—and not so surprised—that there was only one guard, skinny and nervous looking. Instead of watching me, he paced around mumbling to himself.

It didn’t take long before I spotted the glass cabinet with the Gold Buddha. Even though I was not an art historian, I could tell Floating Cloud’s was the masterpiece—the gold shone with a mysterious luster from age, and the Buddha’s face was alive with deep compassion and wisdom. I strained my eyes to read the small description next to the statue inside the cabinet:

Made in the Tang dynasty (ninth century). This statue is pure gold with a halo, bead necklace, and lotus flower seat. Buddha’s face is serene, with eyes half closed in meditation and legs crossed in the full lotus position.

Then I noticed a small keyhole at the lower right-hand corner of the glass case. After looking around to make sure that no one was in the room, I took out my Swiss Army knife and used the screwdriver to see if the lock would budge. But no luck. Then I noticed, to my delight, that next to the Gold Buddha was the Diamond Sutra. Resting on a red, wooden stand, the rolled-up sutra was only opened to the first two pages.

The description next to it read:

Though written in Chinese, the text is one of the most important sacred works of the Buddhist religion originally founded in India. By the time this sutra was made, woodblock printing had been practiced in the Far East for more than a century.

This scroll was copied by the high monk Xian De from the eleventh-century Song Dynasty. Xian used his own blood and spent a year in total isolation to complete writing the sutra. Imbued with the high monk’s blood, intense faith, and spirituality, this masterpiece was believed to possess magical power to bless and protect.

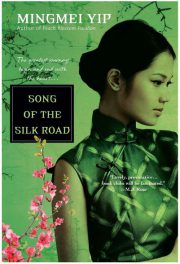

"Song of the Silk Road" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Song of the Silk Road". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Song of the Silk Road" друзьям в соцсетях.