Many times I woke up in the middle of the night with Alex sound asleep next to me. Against the omnipresent silence in this deep womb of darkness, his soft breathing, the ticking of my clock, and the singing of the distant sand were all I needed and cared about.

I noticed his endearing habit—whenever he turned over in his sleep, he’d search for me, then wrap me in his arms, ever so gently, as if I were his newborn baby girl. Or he’d reach for my hand and take it into his. This innocent act deeply touched my heart. I felt loved and needed, like a mother whose baby’s hungry lips relentlessly sought her swelling, generous nipples. So nurturing, so erotic, and so heartbreaking. Had his mother held him like this before she gave him up—his tiny body in her arms, her nipple between his hungry lips?

7

The Herbalist Healer

Alex had been living with me for more than a week. The more days we spent together, the more I agonized over whether I should tell him why I was traveling alone on the Silk Road. Would he start to covet my inheritance and stop loving me for who I was? I didn’t have the slightest impression that greed could be inside his brainy head or hidden behind his innocent face. But one could never tell. Twenty-one or eighty-one, men covet the same things—money, power, status, high-fat gourmet food, pretty women, mind-blowing sex.

Then one day Alex reminded me that his parents would be visiting soon and that he would travel with them around China. Another surprise came when he said that after the family’s vacation, he’d take me to meet them.

I didn’t know how to respond to this. This kid was clearly serious about me. But what about his parents? Would they like me and approve of our relationship, or would they see me as the older woman who had shamelessly seduced their young son?

The morning of Alex’s departure to meet his parents in Urumqi, after we had breakfast and I helped him pack, he drew me into his arms and kissed me with a dying-to-be-relieved desire. We ended up making love on the floor.

When we finally finished our urgent business and were by the door about to leave, he turned to me. “Lily, I’ll miss you.”

“I’ll miss you, too, Alex.”

“Be safe.” He sighed heavily.

“Something wrong?”

“I worry about you. Anyway, I can…”

“Don’t worry, Alex, I have Keku and her husband.”

“All right. I’ll be back before you know it.”

I walked Alex to the waiting donkey cart that would carry him to the next village to catch the bus to Urumqi. He hopped on, threw down his backpack, then leaned over to cup my face, kissing me deeply.

Then I watched and waved until his windblown hair and lean body were carried away into the distance above the four rickety wheels.

Without my young lover with me, everything felt different. The desert, once beautiful and poetic, put on an ominous mask. The birds’ calls were cries of hungry ghosts looking for carcasses; the blowing wind, sobs of a heartbroken woman; the shifting of sands, eerie funeral songs.

I saw my landlady and neighbor Keku almost every day, my only friend in this small, dilapidated village. Sometimes she’d come to my cottage with her four-year-old son, Mito. Other times I’d knock on her door and Keku would invite me in. We’d sit on the carpeted floor by the window of her mud house, chat, and watch the sunset. Next to us, Mito would quietly play with plastic toys, desert plants, the sand under his feet, little insects, or would grasp the already-frayed hem of Keku’s dress, long worn because of his constant pulling to get motherly attention.

When I visited Keku, sometimes her woman friends were also there. Although they didn’t understand what my landlady and I talked about, they looked happy just sitting on the brick “bed” together to sip milk tea, talk in their Uyghur language, marvel at one another’s colorful bodices and knotted headscarves, and look at me with admiration. Once in a while Keku would translate our conversation to them. Funny or not, they’d all giggle till their backs arched into pretty curves, all the time looking at me admiringly.

I sought all the friendship I could get. The group of women was a major source for me to know what was happening in this remote village, not to mention that I was lonely and needed to be around people after Alex’s departure. But I refrained from making friends with men. Having had enough complications in my trip and in my life, gossip was the last thing I wanted. I was pretty sure Keku and the others were well aware of Alex’s existence but were too intimidated or embarrassed to inquire.

Most nights I’d think of Alex and could not sleep. Was he having a good time with his parents? Did he miss me as I did him?

Now all by myself, I also became very sensitive to things around me, including possible vibrations from the graveyard. I had already made a few trips there during the daytime, walking around, feeling its qi, meditating. Sometimes I’d just stare at the graves and the remnants of red paint on the thin boards. Did these belong to a family? I hoped not. What had happened?

Feeling unbearably sad and sorry, I’d always say a prayer to pacify the dead and their living relatives, if any.

The weeks slipped by, and so one day I decided it was time to put everything else aside and prepare for my journey. The first thing I needed to figure out was how to reach one of the highest peaks of the Mountains of Heaven to collect a special plant—snow lotus—required by Mindy Madison.

I had no idea how difficult, or dangerous, the trip might be. I needed to gather information from someone who knew both herbs and the mountain. Maybe an herbalist. Once during our casual conversation I asked Keku if she knew any; to my delight, her answer was yes.

“One in next village.”

“You’re his patient?”

She shook her head. “No. Never saw. Only heard very good.”

When I asked more, she said, “Go to his store and ask him. My husband, Abu, knows. He can take you there.”

Sounds like a plan.

The next day I rode behind Keku’s husband, Abu, on his motorcycle to the neighboring village to visit the herbalist, who was named Lop Nor. When Abu pulled to a stop and pointed to a small store, I was surprised to find that it was not located in the middle of the village but on its edge where there were practically no people around.

I got off the motorcycle, thanked Abu, and walked toward the store.

As I stepped inside the small place, what entered my vision was a tall Uyghur man in his forties, standing behind a counter and cautiously weighing herbs with a dainty scale that looked comically disproportionate to his strong build. He was wearing a white shirt and a gray muslin hat.

The man looked up and our eyes met.

Startled, I recognized the sad-faced man from the graveyard!

I forced a smile, stammering in Chinese. “Morning, are… you the herbalist?”

“Yes. I’m Lop Nor. You’ve come to see me?”

Good, at least he spoke Mandarin as I’d hoped.

I nodded, still feeling shocked by the discovery. To calm myself, I took a few deep breaths to inhale the soothing herbal aroma. Then I looked around the small, clean store, liking what I saw. Behind the herbalist stood a red lacquered medicine cabinet with drawers labeled with names of different herbs ranging from ginseng, red date, cinnamon twig, tangerine peel, chrysanthemum flowers, angelica, to something strange sounding like gromwell, motherwort, sealwort, henbane seed, fungus caterpillar, root of membranous milk vetch. On top were tall jars containing corpses of sea creatures or bugs drowning in yucky, yellowish liquid. Against another wall were placed four chairs above which hung a blanket with pleasing, abstract Islamic patterns. I noticed we were the only people in the store.

“Miss, please take a seat and tell me how you are not feeling well.”

I sat across from him on the other side of the counter. “Oh, I’m not sick, I… just need some herbs to enhance my qi.”

He looked at me intensely, probably trying to figure what kind of herbs I needed. As he towered over me, I examined this Uyghur man that I’d accidentally seen in the graveyard, noting his high cheekbones, hazel eyes, tea-laced-with-milk hair, and lined face. A mystery man. A sad man. I sensed that standing in front of me was a soul suffering from something beyond my experience and understanding.

Sitting down, he said in his soothing bass voice, “Put your hand on the counter and let me take your pulse.”

The glass felt cool on my skin. The herbalist, with acute concentration, pressed together his index, middle, and ring fingers on my wrist.

The creases on his forehead read like abstruse philosophical truths etched in an esoteric language waiting to be deciphered. His eyes, though sad, also emanated strong yang energy. However, what really caught my attention and made my heart ache were his hands—large, brown, leathery, scarred. His fingers were thick, calloused, tipped with nails lined with faint dark ridges. What had this man done with those hands—just collecting herbs on the mountain, or digging graves to house ghosts?

As his right hand was taking my pulse, his left stroked a big, translucent white jade pendant that hung from his neck on a leather string. A sense of déjà vu welled up inside me while my arms began to tingle. I sensed this must be something that he’d loved and lost from a previous life.

It was an exquisite piece, and I wondered how it came to be in this bare village. Was it a priceless family heirloom?

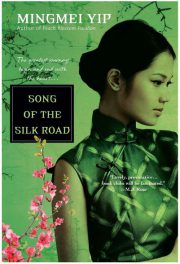

"Song of the Silk Road" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Song of the Silk Road". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Song of the Silk Road" друзьям в соцсетях.