“Of course not.” She pursed her lips and looked away. “Though I hope I have given you no reason to think I would do such a thing.”

It was Hamish’s turn to be chagrinned, and he realized that Miss Lorimer had her own, different disappointments than either Elspeth or himself. He could—and would at his first opportunity—find Elspeth and make all right between them. Miss Lorimer, with her trade-earned fortune and her brewer of a father, would have a harder time finding herself a new prospect for a husband.

“I hope you take no offense to yourself, Miss Lorimer. I regret deeply that this misunderstanding has happened, and would have been honored to act upon my family’s wishes were I not already contracted, and in love with another.”

Hamish had meant the admission to be for Miss Lorimer, to salve her pride and wounded feelings, but the moment he said it, he knew that he meant every word.

His wife. His love.

Ye gods. Truer words he had never spoken.

And speak them again he needed to—posthaste. “If you’ll excuse me, Miss Lorimer, Mr. Lorimer, I have most urgent business I must attend to.”

***

With Fergus’ adroit assistance Hamish was dressed in a suitably gentlemanly suit of clothes, seated upon a hunter of more aristocratic bloodlines than his own, and ready to present himself to the ladies of Dove Cottage whereupon he would soothe the upset of the morning, and plight his troth.

But the ladies of Dove Cottage were more militant than he expected. They would not answer the bell at their door, even though he could hear them, talking between themselves inside.

So Hamish took himself to the window. “Dear ladies, I have come to make my peace and make my honorable intentions known to you. But I cannot do so through a closed door. But, do you know what?” He changed his mind. “I can do it through a window. I love Elspeth enough that I don’t mind how I ask for the honor of her hand.”

The silence that met this proposal would have been deafening but for the fact that he was in a country lane, where it was never really quiet—the hedgerows fairly rattled with all manner of answers.

“But we don’t know you,” was finally the plaintive response.

“Then let me introduce myself properly, ladies. I am Mr. Hamish Cathcart of Edinburgh, son of the Earl Cathcart of Renfrewshire, and other various and assorted places that I am sure he would be glad and proud to tell you about, but which bore me to tears. Because the point of this visit is to assure you that though my fortune is currently small, it is independent, and I have every confidence that I will increase it if you will do me the honor of letting Miss Elspeth Otis become by helpmeet and wife, and be by my side.”

It was a rather long, rambling sort of proposal, but Hamish was pleased and proud of it, for he meant never to make another. Though he did not yet appear to be finished with this one.

One of the sisters Murray peered around the open door. “We suppose you had better come in.”

Hamish was careful to wipe his boots, and take off his hat so as not to dirty the floor, nor crowd the ceiling of the snug little cottage. He bowed to the two tiny sisters. “Thank you for seeing me. I am honored.”

The smaller of the two ladies pursed her lips in disagreement. “We didn’t want the neighbors to see you standing in the garden like a scarecrow.”

A well-dressed, aristocratic scarecrow, he nearly corrected. But he did not. “I see. Then let me do all I can to convince you of my sincerity. I love and admire and esteem your niece, and I should be the happiest of men were you to honor me with her hand, but I will tell you, too, that I mean to have her to wife, whether you give your blessing or not. We are both of age. And this is Scotland. And”—he threw one last piece of fuel on the fire—“we are handfasted, and so engaged.”

They were not yet impressed. “Have you the backing of your family?”

This question, he had not expected, but he was equal to the moment. “I belong to an ancient and honorable family, Miss Murray, but my own name and my own character are all I can offer your niece. I hope that they are enough to secure your approval.”

“She’s a bastard.” The smaller of the two ladies thrust the accusation at him like a sword.

But he had weapons of his own—righteous anger and steadfast love. “Elspeth may be illegitimate, but bastardy is not a part of her character.” He worked to keep the steel from his voice. “And I will not have that word spoken in reference to her again. Do I make myself clear?”

In silence the sisters Murray looked at each other in silent communication before they turned to him.

“We could not give her to you if you felt otherwise, Mr. Cathcart.”

Relief slid slowly into his veins like a cool bath, calming him, and firming his resolve. “Then all that remains is for me to plight my troth to Elspeth. Where is she?”

Another long speaking look passed between the women before the older of the two spoke. “We’re afraid she’s gone, Mr. Cathcart. We are ashamed to say we drove her out, and can only hope that she is gone to her Aunt Ivers in Edinburgh.”

Well. Hamish withstood the blow with all the sanguinity he could muster. “Then I think, my dear aunts, that we had best get you two packed for Edinburgh.”

Chapter 23

Elspeth was tired and footsore by the time she made St. Andrew Square, for she had walked a long way past the next village before she had found a farmer’s dray heading for Edinburgh’s Grass Market. But her spirits were revived when Aunt Augusta opened the door herself.

“My darling girl!” She enveloped her in a tight, heartfelt embrace. “Oh, it is so lovely to have you back. We have so much to do. I am so very, very excited and pleased—” She took another look at Elspeth’s face. “But what is wrong? Where is Mr. Cathcart?”

“Gone to the devil for all I know—he did not deign to come. I left him with his betrothed.” Elspeth curbed her bitterness and firmed her resolve. “As for me, I’ve come to Edinburgh to be a wastrel, just like my father. Blood will out, the Aunts said, so here I am.”

Instead of gasping in shock as she might have expected, Lady Augusta broke into a smile so wide and bright, Elspeth might have put out her chilled hands to the warmth. “Bless them for being so stupidly missish.” Aunt Augusta clasped her hand to lead her upward to the drawing room. “Their loss is my gain. And your father was a wastrel only because he wasted his gifts—squandered on women of no character and wine of little distinction in the terrible grief of the loss of your mother. And you, my darling brave girl, will never do that.”

“I thank you for your enthusiastic and unwavering confidence, Aunt Augusta, but the unhappy truth of the matter is that I find myself in an awful pickle.”

“And by awful pickle,” that kind lady asked gently, “do you mean falling in love with Mr. Cathcart?”

It was a long moment before Elspeth trusted herself to speak clearly. “I suppose I do. More or less.” It was all so complicated and sad. She had thought she loved him, most fervently. But now she was angry as well as sad. “But before I can allow myself to love Mr. Hamish Cathcart, the man needs to be taught a lesson.”

“Oh, yes.” Lady Augusta clasped her hands together, as if in prayer. “How entirely delightful. I offer you my full and wickedly experienced assistance on the instant, for we must act quickly, at once!” She drew Elspeth to her in a fierce embrace. “Oh, I knew I should grow to love you, now more than ever before.” She clapped her hands together, immediately calling for the butler. “Reeves, call all the staff immediately. As my dearest Admiral Ivers would have said, pipe all hands to battle stations!”

Battle stations turned out to be a great deal more comfortable that Elspeth might have thought—she was bathed and coiffed and fed and dressed in a gown of cerulean blue silk that shimmered and whispered encouragement when she walked.

“Perfection,” Aunt Augusta decreed as her dresser put the finishing touches on Elspeth’s ensemble. “Pure, absolute perfection. Nothing more—her head bare and honest. Yes,”—she stood back to peruse Elspeth once more—“You’ll do perfectly.”

“Do for what, Aunt Augusta?”

“The occasion,” she answered, as if that explained anything. “Battle armor, as it were, though I should think it safe so say you have already won the war.”

“What war?”

Aunt Augusta favored her with that mischievous smile that carved dimples deep into her cheeks. “All in good time, my darling. And it is time”—she picked up her own silk skirts and proceeded to the door—“for us to go.”

“To where, pray, madam?

“To church.” She swept down the steps and into the waiting carriage.

“But it is a Thursday morning,” Elspeth objected. “Is there some holy day that I did not know existed?”

“There is indeed,” Aunt Augusta said with mischievous tartness. “Now get yourself into the carriage, and say not another word.”

They had not far to go, only around the corner onto George Street, headed for the high-clocked steeple of St. Andrew’s kirk.

He was waiting beneath the tall columned portico, her Mr. Hamish Cathcart, looking as tall and mischievous and Scots as ever she might have imagined.

Aunt Augusta took her elbow and urged her on.

Hamish just smiled.

He was dressed in the old style, in the distinct blue, red and green plaid of the Clan Cathcart tartan, with a sword hung at his side. He was breathtaking and impressive. And confusing.

And what was more confusing was the way Hamish offered her his hand, and wordlessly led her into the kirk, past the astonishing sight of the Aunts Murray, smiling wistfully and dabbing at their damp eyes with familiar worn lace-edged handkerchiefs.

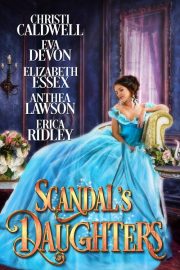

"Scandal’s Daughters" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Scandal’s Daughters". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Scandal’s Daughters" друзьям в соцсетях.