"I can see you, Mastriani," Mr. C said, in his usual lazy drawl. "Move up one."

I looked at the empty seat in front of me.

"Oh, no, Mr. C," I said. "That's Amber's seat. She must be late or something. But she'll be here."

There was a strange silence. Really. I mean, not all silences are the same, even though you would think by definition—the absence of sound—they would be.

This one, however, was more silent than most silences. Like everyone, all at once, had suddenly decided to hold their breath.

Mr. Cheaver—who was also holding his breath—narrowed his eyes at me. There weren't many teachers at Ernie Pyle High whom I could stand, but Mr. C was one of them. That's because he didn't play favorites. He hated every single one of us just about equally. He maybe hated me a little less than some of my peers, because last year, I had actually done the homework he'd assigned, as I'd found World Civ quite interesting, especially the parts about the wholesale slaughter of entire populations.

"Where have you been, Mastriani?" Mr. Cheaver wanted to know, "Amber Mackey's not coming back this year."

Seriously, how was I to have known?

"Oh, really?" I said. "Did her parents move or something?"

Mr. C just looked at me in a very displeased manner, while the rest of the class suddenly exhaled, all at once, and started buzzing instead. I had no idea what they were talking about, but from the scandalized looks on their faces, I could tell I had really put my foot in it this time. Tisha Murray and Heather Montrose looked particularly contemptuous of me. I thought about getting up and cracking their heads together, but I've tried that before, and it doesn't actually work.

But another thing I was trying to "make an effort" to do my junior year—besides cause some innocent young man to fall completely in love with me so I could stroll, ever so casually, hand-in-hand with him in front of the garage where Rob had been working since he graduated last year—was not get into fistfights. Seriously. I had spent enough weeks in detention back in tenth grade thanks to my inability to control my rage impulse. I was not going to make the same mistake this year.

That was one of the other reasons—besides my total lack of clean Levis—that I'd gone for the miniskirt. It wasn't so easy to knee somebody in the groin while clad in a Lycra/rayon blend.

Maybe, I thought, as I observed the expressions of the people around me, Amber had gotten herself knocked up, and everyone knew it but me. Hey, in spite of Coach Albright's Health class, mandatory for all sophomores, in which we were warned of the perils of unsafe sex, it happens. Even to cheerleaders.

But apparently not to Amber Mackey, since Mr. C looked down at me and went, tonelessly, "Mastriani. She's dead."

"Dead?" I echoed. "Amber Mackey?" Then, like an idiot: "Are you sure?"

I don't know why I asked him that. I mean, if a teacher says somebody is dead, you can pretty much count on the fact that he's telling the truth. I'd just been so surprised. It probably sounds like a cliche, but Amber Mackey had always been . . . well, full of life. She hadn't been one of those cheerleaders you could hate. She'd never been purposefully mean to anyone, and she'd always had to try really hard to keep up with the other girls on the squad, both socially as well as athletically. Academically, she'd been no National Merit Scholar, either, if you get my drift.

But she'd tried. She'd always really tried.

Mr. C wasn't the one who answered me. Heather Montrose was.

"Yeah, she's dead," she said, her carefully glossed upper lip raised in disgust. "Where have you been, anyway?"

"Really," Tisha Murray said. "I'd have thought Lightning Girl would have had a clue, at least."

"What's the matter?" Heather asked me. "Your psychic radar on the fritz or something?"

I am not precisely what you would call popular, but since I do not make a habit of going around being a total bitch to people, like Heather and Tisha, there are folk who actually will come to my defense against them. One of them, Todd Mintz—linebacker on the varsity football team who was sitting behind me—went, "Jesus, would you two cool it? She doesn't do the psychic thing anymore. Remember?"

"Yeah," Heather said, with a flick of her long, blonde mane. "I heard."

"And I heard," Tisha said, "that just two weeks ago, she found some kid who'd been lost in a cave or something."

This was patently untrue. It had been a month ago. But I wasn't about to admit as much to the likes of Tisha.

Fortunately, I was spared from having to make any reply whatsoever by the tactful intervention of Mr. Cheaver.

"Excuse me," Mr. C said. "But while this may come as a surprise to some of you, I have a class to conduct here. Would you mind saving the personal chat until after the bell rings? Mastriani. Move up one."

I moved up one seat, as did the rest of our row. As we did so, I whispered to Todd, "So what happened to her, anyway?" thinking Amber had gotten leukemia or something, and that the cheerleaders would probably start having car washes all the time in order to raise money to help fight cancer. The Amber Fund, they'd probably call it.

But Amber's death had not been from natural causes, apparently. Not if what Todd whispered back was the truth.

"They found her yesterday," he said. "Facedown in one of the quarries. Strangled to death."

Oh.

C H A P T E R

2

Now, who would do that?

Seriously. I want to know.

Who would strangle a cheerleader, and dump her body at the bottom of a limestone quarry?

I can certainly understand wanting to strangle a cheerleader. Our school harbors some of the meanest cheerleaders in North America. Seriously. It's like you have to pass a test proving you have no human compassion whatsoever just to get on the squad. The cheerleaders at Ernest Pyle High would sooner pluck out their own eyelashes than deign to speak to a kid who wasn't of their social caliber.

But actually to go through with it? You know, off one of them? It hardly seemed worth the effort.

And anyway, Amber hadn't been like the others. I had actually seen Amber smile at a Grit—the derogatory name for the kids who were bused in from the rural routes to Ernie Pyle, the only high school in the county; kids who did not live on a rural route are referred to, imaginatively, as Townies.

Amber had been a Townie, like Ruth and me. But I had never observed her lording this fact over anyone, as I often had Heather and Tisha and their ilk. Amber, when selected as a team captain in PE, had never chosen all Townies first, then moved on to Grits. Amber, when walking down the hall with her books and pompons, had never sneered at the Grits' Wranglers and Lee jeans, the only "dungarees" they could afford. I had never seen Amber administer a "Grit test": holding up a pen and asking an unsuspecting victim what she had in her hand. (If the reply was "A pen," you were safe. If, however, you said, "A pin," you were labeled a Grit and laughed at for your Southern drawl.)

Is it any wonder that I have anger-management issues? I mean, seriously. Wouldn't you, if you had to put up with this crap on a daily basis?

Anyway, it just seemed to me a shame that, out of all the cheerleaders, Amber had been the one who'd had to die. I mean, I had actually liked her.

And I wasn't the only one, as I soon found out.

"Good job," somebody hissed as they passed me in the hallway while I walked to my locker.

"Way to go," somebody else said as I was coming out of Bio.

And that wasn't all. I got a sarcastic "Thanks a lot, Lightning Girl," by the drinking fountains and was called a "skank" as I went by a pack of Pompettes, the freshmen cheerleaders.

"I don't get it," I said to Ruth in fourth period Orchestra as we were unpacking our instruments. "It's like people are blaming me or something for what happened to Amber. Like I had something to do with it."

Ruth, applying rosin to her cello bow, shook her head.

"That's not it," she said. She had gotten the scoop, apparently, in Honors English. "I guess when Amber didn't come home Friday night, her parents called the cops and stuff, but they didn't have any luck finding her. So I guess a bunch of people called your house, you know, thinking you might be able to track her down. You know. Psychically. But you weren't home, of course, and your aunt wouldn't give any of them my dad's emergency cell number, and there's no other way to reach us up at our summer place, so …"

So? So it was my fault. Or at the very least, Great-aunt Rose's fault. Now I had yet another reason to resent her.

Never mind that I have taken great pains to impress upon everyone the fact that I no longer have the psychic ability to find missing people. That thing last spring, when I'd been struck by lightning and could suddenly tell, just by looking at a photo of someone, where that someone was, had been a total fluke. I'd told that to the press, too. I'd told it to the cops, and to the FBI. Lightning Girl—which was how I'd been referred to by the media for a while there—no longer existed. My ESP had faded as mysteriously as it had arrived.

Except of course it hadn't really. I'd been lying to get the press—and the cops—off my back.

And, apparently, everyone at Ernest Pyle High School knew it.

"Look," Ruth said as she practiced a few chords. "It's not your fault. If anything, it's your whacked-out aunt's fault. She should have known it was an emergency and given them my dad's cell number. But even so, you know Amber. She wasn't the shiniest rock in the garden. She'd have gone out with Freddy Krueger if he'd asked her. It really isn't any wonder she ended up facedown in Pike's Quarry."

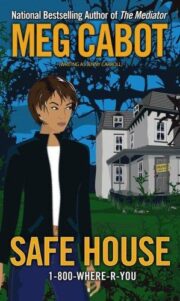

"Safe House" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Safe House". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Safe House" друзьям в соцсетях.