If this was meant to comfort me, it did not. I slunk back to the flute section, but I could not concentrate on what Mr. Vine, our Orchestra teacher, was saying to us. All I could think about was how at last year's talent show, Amber and her longtime boyfriend—Mark Leskowski, the Ernie Pyle High Cougars quarterback—had done this very lame rendition of Anything You Can Do I Can Do Better, and how serious Amber had been about it, and how certain she'd been that she and Mark were going to win.

They didn't, of course—first prize went to a guy whose Chihuahua howled every time it heard the theme song to Seventh Heaven—but Amber had been thrilled by winning second place.

Thrilled, I couldn't help thinking, to death.

"All right," Mr. Vine said just before the bell rang. "For the rest of the week, we'll hold chair auditions. Horns tomorrow, strings on Wednesday, winds on Thursday, and percussion on Friday. So do me a favor and practice for a change, will you?"

The bell for lunch rang. Instead of tearing out of there, though, most people reached beneath their seats and pulled out sandwiches and cans of warm soda. That's because the vast majority of kids in Symphonic Orchestra are geeks, afraid of venturing into the caf, where they might be ridiculed by their more athletically endowed peers. Instead, they spend their lunch hour in the music wing, munching soggy tuna fish sandwiches and arguing about who makes a better starship captain, Kirk or Picard.

Not Ruth and me, though. In the first place, I have never been able to stand the thought of eating in a room in which the words "spit valve" are mentioned so often. In the second place, Ruth had already explained that what with our new wardrobes—and her recent weight loss—we were not going to hide in the bowels of the music wing. No, we were going to see and be seen. Though Ruth's heart still belonged to Scott, the fact was, he lived three hundred miles away. We had only ten more months to secure a prom date, and Ruth insisted we start immediately.

Before we got out of the orchestra room, however, we were accosted by one of my least favorite people, fellow flutist Karen Sue Hankey, who made haste to inform me that I could give up all hope of hanging onto third chair this year, as she had been practicing for four hours a day and taking private lessons from a music professor at a nearby college.

"Great," I said, as Ruth and I tried to slip past her.

"Oh, and by the way," Karen Sue added, "that was real nice, how you were there for Amber and all."

But if I thought that'd be the worst I'd hear on the subject, I was sadly mistaken. It was ten times worse in the cafeteria. All I wanted to do was get my Tater Tots and go, but do you think they'd let me? Oh, no.

Because the minute we got in line, Heather Montrose and her evil clone Tisha slunk up behind us and started making remarks.

I don't get it. I really don't. I mean, the way I'd left things last spring, when school let out, was that I didn't have my psychic powers anymore. So how was everyone so sure I'd lied? I mean, the only person who knew any differently was Ruth, and she'd never tell.

But somebody had been doing some talking, that was for sure.

"So, what's it like?" Heather wanted to know as she sidled up behind us in the grill line. "I mean, knowing that somebody died because of you."

"Amber didn't die because of anything I did, Heather," I said, keeping my eyes on the tray I was sliding along past the bowls of sickly looking lime Jell-O and suspiciously lumpy tapioca pudding. "Amber died because somebody killed her. Somebody who was not me."

"Yeah," Tisha agreed. "But, according to the coroner, she was held against her will for a while before she was killed. They were lickator marks on her."

"Ligature," Ruth corrected her.

"Whatever," Tisha said. "That means if you'd been around, you could have found her."

"Well, I wasn't around," I said. "Okay? Excuse me for going on vacation."

"Really, Tish," Heather said in a chiding voice. "She's got to go on vacation sometime. I mean, she probably needs it, living with that retard and all."

"Oh, God," I heard Ruth moan. Then she carefully lifted her tray out of the line of fire.

That's because, of course, Ruth knew. There aren't many things that will make me forget all the anger-management counseling I've received from Mr. Goodhart, upstairs in the guidance office. But even after nearly two years of being instructed to count to ten before giving in to my anger—and nearly two years of detention for having failed miserably in my efforts to do so—any derogatory mention of my brother Douglas still sets me off.

About a second after Heather made her ill-advised remark, she was pinned up against the cinder block wall behind her.

And my hand was what was holding her there. By her neck.

"Didn't anyone ever tell you," I hissed at her, my face about two inches from hers, "that it is rude to make fun of people who are less fortunate than you?"

Heather didn't reply. She couldn't, because I had hold of her larynx.

"Hey." A deep voice behind me sounded startled. "Hey. What's going on here?"

I recognized the voice, of course.

"Mind your own business, Jeff," I said. Jeff Day, football tackle and all around idiot, has also never been one of my favorite people.

"Let her go," Jeff said, and I felt one of his meaty paws land on my shoulder.

An elbow, thrust with precision, soon put an end to his intervention. As Jeff gasped for air behind me, I loosened my hold on Heather a little.

"Now," I said to her. "Are you going to apologize?"

But I had underestimated the amount of time it would take Jeff to recover from my blow. His sausage-like fingers again landed on my shoulder, and this time, he managed to spin me around to face him.

"You let her alone!" he bellowed, his face beet red from the neck up.

I think he would have hit me. I really do. And at the time, I sort of relished the idea. Jeff would take a swing at me, I would duck, and then I'd go for his nose. I'd been longing to break Jeff Day's nose for some time. Ever since, in fact, the day he'd told Ruth she was so fat they were going to have to bury her in a piano case, like Elvis.

Only I didn't get a chance to break Jeff's nose that day. I didn't get a chance because someone strode up behind him just as he was drawing back his fist, caught it midswing, and wrapped his arm around his back.

"That how you guards get your kicks?" Todd Mintz demanded. "Beating up girls?"

"All right." A third and final voice, equally recognizable to me, broke the little party up. Mr. Goodhart, holding a tossed salad and a container of yogurt, nodded toward the cafeteria doors. "All of you. In my office. Now."

Jeff and Todd and I followed him resentfully. It wasn't until we were nearly at the door that Mr. Goodhart turned and called, with some exasperation, "You, too, Heather," that Heather came slinking along after us.

In Mr. Goodhart's office, we were informed that we were not "Starting the Year Off Right," and that we really ought to be "Setting a Better Example for the Younger Students," seeing as how we were all juniors now. It would "Behoove Us to Come Together and Try to Get Along," especially in the wake of the tragedy that had occurred over the weekend.

"I know Amber's death has shaken us all up." Mr. Goodhart said, sincerity oozing out of his every pore. "But let's try to remember that she would have wanted us to comfort one another in our grief, not get torn apart by petty bickering."

Out of all of us, Heather was the only one who'd never before been dragged into a counselor's office for fighting. So, of course, instead of keeping her mouth shut so we could all get out of there, she pointed a silk-wrapped fingernail at me and went, "She started it."

Todd and Jeff and I rolled our eyes. We knew what was coming next.

Mr. Goodhart launched into his "I Don't Care Who Started It, Fighting Is Wrong" speech. It lasted four and a half minutes, twenty seconds longer than last year's version. Then Mr. Goodhart went, "You're all good kids. You have unlimited potential, each of you. Don't throw it all away through violence against one another."

Then he said everyone could go.

Everyone except me, of course.

"It wasn't my fault," I said as soon as the others were gone. "Heather called Douglas a retard."

Mr. Goodhart shoveled a spoonful of yogurt into his mouth.

"Jess," he said, with his mouth full. "Is this how it's going to be again? You, in my office every day for fighting?"

"No," I said. I tugged on the hem of my miniskirt. Though I knew I looked good in it, I did feel just a tad naked. Also, it hadn't worked. I'd gotten into a fight anyway. "I'm trying to do what you said. You know, the whole counting to ten thing. But it's just . . . everyone is going around, blaming me."

Mr. Goodhart looked puzzled. "Blaming you for what?"

"For what happened to Amber." I explained to him what everyone was saying.

"That's ridiculous," Mr. Goodhart said. "You couldn't have stopped what happened to Heather, even if you did still have your powers. Which you don't." He looked at me. "Do you?"

"Of course not," I said.

"So where are they getting the idea that you do?" Mr. Goodhart wondered.

"I don't know." I looked at the salad he was eating. "What happened to you?" I asked. "Where's the Quarter Pounder with cheese?" Ever since I'd met him, Mr. Goodhart's lunches had always consisted of a burger with a side of fries, usually super-sized.

He made a face. "I'm on a diet," he said. "Blood pressure and cholesterol are off the scale, according to my GP."

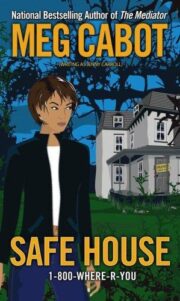

"Safe House" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Safe House". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Safe House" друзьям в соцсетях.