"Of course."

I smiled and we kissed once more before I turned and climbed the steps to the front galerie. Paul waited until I walked in and then he went to his scooter and drove away. The moment Grandmère Catherine turned to greet me, I knew she had heard about Grandpère Jack. One of her good friends couldn't wait to bring her the news first, I was sure.

"Why didn't you just let the police cart him off to jail? That's where he belongs, making a spectacle of himself in front of good folks with all those children in town, too," she said, wagging her head. "What did you and Paul do with him?"

"We took him back to his shack, Grandmère, and if you saw how it was . . ."

"I don't have to see it. I know what a pigsty looks like," she said, returning to her biscuits.

"He called me Gabrielle when he first set eyes on me," I said.

"Doesn't surprise me none. He probably forgot his own name, too."

"At the shack, he mumbled a lot."

"Oh?" She turned back to me.

"He said something about someone being in love and what was the difference about the money. What does all that mean, Grandmère?"

She turned away again. I didn't like the way her eyes skipped guiltily away when I tried to catch them. I knew in my heart she was hiding something.

"I wouldn't know how to begin to untangle the mess of words that drunken mind produces. It would be easier to unravel a spiderweb without tearing it," she said.

"Who was in love, Grandmère? Did he mean my mother?"

She was silent.

"Did he gamble away her money, your money?" I pursued.

"Stop trying to make sense out of something stupid, Ruby. It's late. You should go to bed. We're going to early Mass, and I must tell you, I'm not happy about you and Paul carting that man into the swamp. The swamp is no place for you. It's beautiful from a distance, but it's the devil's lair, too, and wrought with dangers you can't even begin to imagine. I'm disappointed in Paul for taking you there," she concluded.

"Oh, no, Grandmère. Paul didn't want me to go along. He wanted to do it himself, but I insisted."

"Still, he shouldn't have done it," she said, and turned to me, her eyes dark. "You shouldn't be spending all your time with one boy like this. You're too young."

"I'm fifteen, Grandmère. Some fifteen-year-old Cajun girls are already married, some with children."

"Well, that's not going to happen to you. You're going to do better, be better," she said angrily.

"Yes, Grandmère. I'm sorry. We didn't mean . . ."

"All right," she said. "It's over and done with. Let's not ruin an otherwise special day by talking about your Grandpère anymore. Go to sleep, Ruby. Go on," she ordered. "After church, you're going to help me prepare our Sunday dinner. We've got a guest, don't we?" she asked, her eyes full of skepticism.

"Yes, Grandmère. He's coming."

I left her, my mind in a spin. The day had been filled with so many good things and so many bad. Maybe Grandmère Catherine was right; maybe it was better not to try to fathom the dark things. They had a way of polluting the clear waters, spoiling the fresh and the wonderful bright things. It was better to dwell on the happy events.

It was better to think about my paintings hanging in a New Orleans gallery . . . to remember the touch of Paul's lips on mine and the way he made my body sing . . . to dream about a perfect future with me painting in my own art studio in our big house on the bayou. Surely the good things had a way of outweighing the bad, otherwise we would all be like Grandpère Jack, lost in a swamp of our own making, not only trying to forget the past, but trying to forget the future as well.

3

I Wish We Were a Family

In the morning Grandmère Catherine and I put on our Sunday clothes. I brushed my hair and tied it up with a crimson ribbon and she and I set out for church, Grandmère carrying her gift for Father Rush, a box of her homemade biscuits. It was a bright morning with silky white clouds lazily making their way across the nearly turquoise sky. I took a deep breath, inhaling the warm air seasoned with the salt of the Gulf of Mexico. It was the kind of morning that made me feel bright and alive, and aware of every beautiful thing in the bayou.

The moment we walked down the steps of the galerie, I caught sight of the scarlet back of a cardinal as it flew to its safe, high nest. As we strolled down the road, I saw how the buttercups had blossomed in the ditches and how milk white were the small, delicate flowers of the Queen Anne's lace.

Even the sight of a butcher bird's stored food didn't upset me. From early spring, through the summer and early fall, his fresh kills, lizards and tiny snakes, dried upon the thorns of a thorn tree. Grandpère Jack told me the butcher bird ate the cured flesh only during the winter months.

"Butcher birds are the only birds in the bayou that have no visible mates," he told me. "No female naggin' them to death. Smart," he added before spitting out some tobacco juice and swigging a gulp of whiskey in his mouth. What made him so bitter? I wondered again. However, I didn't dwell on it long, for ahead of us the church loomed, its shingled spire lifting a cross high above the congregation. Every stone, every brick, and every beam of the old building had been brought and affectionately placed there by the Cajuns who worshipped in the bayou nearly one hundred and fifty years before. It filled me with a sense of history, a sense of heritage.

But as soon as we rounded the turn and headed toward the church, Grandmère Catherine stiffened and straightened her spine. A group of well-to-do people were gathered in a small circle chatting in front of the church. They all stopped their conversation and looked our way as soon as we came into sight, a distinct expression of disapproval painted on all their faces. That only made Grandmère Catherine hoist her head higher, like a flag of pride.

"I'm sure they're raking over what a fool your Grandpère made of himself last night," Grandmère Catherine muttered, "but I will not have my reputation blemished by that man's foolish behavior."

The way she stared back at the gathering told them as much. They looked happy to break up to go inside as the time to enter the church for services drew near. I saw Paul's parents, Octavious and Gladys Tate, standing on the perimeter of the throng. Gladys Tate threw a glance in our direction, her hard as stone eyes on me. Paul, who had been talking with some of his school buddies, spotted me and smiled, but his mother made him join her and his father and sisters as they entered the church.

The Tates, as well as some other wealthy Cajun families, sat up front so Paul and I didn't get a chance to talk to each other before the Mass began. Afterward, as the worshippers filed past Father Rush, Grandmère gave him her box of biscuits and he thanked her and smiled coyly.

"I hear you were at work again, Mrs. Landry," the tall, lean priest said with a gently underlying note of criticism in his voice. "Chasing spirits into the night."

"I do what I must do," Grandmère replied firmly, her lips tight and her eyes fixed on his.

"As long as we don't replace prayer and church with superstition," he warned. Then he smiled. "But I never refuse assistance in the battle against the devil when that assistance comes from the pure at heart."

"I'm glad of that, Father," Grandmère said, and Father Rush laughed. His attention was then quickly drawn to the Tates and some other well-to-do congregants who made sizeable contributions to the church. While they spoke, Paul joined Grandmère and me. I thought he looked so handsome and very mature in his dark blue suit with his hair brushed back neatly. Even Grandmère Catherine seemed impressed.

"What time is supper, Mrs. Landry?" Paul asked. Grandmère Catherine shifted her eyes toward Paul's parents before replying.

"Supper is at six," Grandmère told him, and then went to join her friends for a chat. Paul waited until she was out of earshot.

"Everyone was talking about your grandfather this morning," he told me.

"Grandmère and I sensed that when we arrived. Did your parents find out you helped me get him home?"

The look on his face gave me the answer.

"I'm sorry if I caused you trouble."

"It's all right," he said quickly. "1 explained everything." He grinned cheerfully. He was the perpetual cockeyed optimist, never gloomy, doubtful, or moody, as I often was.

"Paul," his mother called. With her face frozen in a look of disapproval, her mouth was like a crooked knife slash and her eyes were long and catlike. She held her body stiffly, looking as if she would suddenly shudder and march away.

"Coming," Paul said.

His mother leaned over to whisper something to his father and his father turned to look my way.

Paul got most of his good looks from his father, a tall, distinguished looking man who was always elegantly dressed and well-groomed. He had a strong mouth and jaw with a straight nose, not too long or too narrow.

"We're leaving right this minute," his mother emphasized.

"I've got to go. We have some relatives coming for lunch. See you later," Paul promised, and he darted off to join his parents.

I stepped beside Grandmère Catherine just as she invited Mrs. Livaudis and Mrs. Thibodeau to our house for coffee and blackberry pie. Knowing how slowly they would walk, I hurried ahead, promising to start the coffee. But when I got to our front yard, I saw my grandfather down at the dock, tying his pirogue to the back of the dingy.

"Good morning, Grandpère," I called. He looked up slowly as I approached.

"Ruby" отзывы

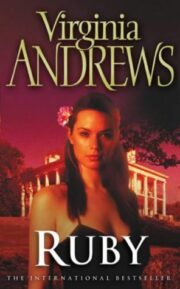

Отзывы читателей о книге "Ruby". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Ruby" друзьям в соцсетях.