"Sleep, sleep? Yeah," he said, turning back toward the Cajun Queen. "Those no good . . . they take your money and then when you voice your opinion about somethin' . . . things ain't what they was around here, that's for sure, that's for damn sure."

"Come on, Grandpère." I tugged his hand and he came off' the steps, nearly tripping and falling on his face. Paul rushed to take hold of his other arm.

"My boat," Grandpère muttered. "At the dock." Then he turned and ripped his hand from mine to wave his fist at the Cajun Queen one more time. "You don't know nothin’. None of you remember the swamp the way it was 'fore these damn oil people came. Hear?"

"They heard you, Grandpère. Now it's time to go home."

"Home. I can't go home," he muttered. "She won't let me go home."

I swung my gaze to Paul who looked very upset for me. "Come along, Grandpère," I urged again, and he stumbled forward as we guided him to the dock.

"He won't be able to navigate this boat himself," Paul declared. "Maybe I should just take him and you should go home, Ruby."

"Oh, no. go along. I know my way through the canals better than you do, Paul," I insisted.

We got Grandpère into his dingy and sat him down. Immediately, he fell over the bench. Paul helped him get comfortable and then he started the motor and we pulled away from the dock, some of the people still watching us and shaking their heads. Grandmère Catherine would hear about this quickly, I thought, and she would just nod and say she wasn't surprised.

Minutes after we pulled away from the dock, Grandpère Jack was snoring. I tried to make him more comfortable by putting a rolled up sack under his head. He moaned and muttered something incoherently before falling asleep and snoring again. Then I joined Paul.

"I'm sorry," I said.

"For what?"

"I'm sure your parents will find out about this tomorrow and be angry."

"It doesn't matter," he assured me, but I remembered how dark Grandmère Catherine's eyes had become when she asked me what his parents thought of his seeing me. Surely they would use this incident to convince him to stay away from the Landrys. What if signs began to appear everywhere saying, "No Landrys Allowed," just like Grandmère Catherine described from the past? Perhaps I really would have to flee from the bayou to find someone to love me and make me his wife. Perhaps this was what Grandmère Catherine meant.

The moon lit our way through the canals, but when we went deeper into the swamp, the sad veils of Spanish moss and the thick, intertwined leaves of the cypress blocked out the bright illumination making the waterway more difficult to navigate. We had to slow down to avoid the stumps. When the moonlight did break through an opening, it made the backs of the gators glitter. One whipped its tail, splash-ing water in our direction as if to say, you don't belong here. Farther along, we saw the eyes of a marsh deer lit up by the moonbeams. We saw his silhouetted body turn to disappear in the darker shadows.

Finally, Grandpère's shack came into view. His galerie was crowded with nets for oyster fishing, a pile of Spanish moss he had gathered to sell to the furniture manufacturers who used it for stuffing, his rocking chair with the accordion on it, empty beer bottles and a whiskey bottle beside the chair and a crusted gumbo bowl. Some of his muskrat traps dangled from the roof of the galerie and some hides were draped over the railing. His pirogue with the pole he used to gather the Spanish moss was tied to his small dock. Paul gracefully navigated us up beside it and shut off the motor of the dingy. Then we began the difficult task of getting Grandpère out of the boat. He offered little assistance and came close to spilling all three of us into the swamp.

Paul surprised me with his strength. He virtually carried Grandpère over the galerie and into the shack. When I turned on a butane lamp, I wished I hadn't. Clothing was strewn all about and everywhere there were empty and partially empty bottles of cheap whiskey. His cot was unmade, the blanket hanging down with most of it on the floor. His dinner table was covered with dirty dishes and crusted bowls and glasses, as well as stained silverware. From the expression on his face, I saw that Paul was overwhelmed by the filth and the mess.

"He'd be better off sleeping right in the swamp," he muttered. I fixed the cot so he could lower Grandpère Jack onto it. Then we both started to undo his hip boots. "I can do this," Paul said. I nodded and went to the table first to clear it off and put the dishes and bowls into the sink, which I found to be full of other dirty dishes and bowls. While I washed and cleaned, Paul went around the shack and picked up the empty cans and bottles.

"He's getting worse," I moaned, and wiped the tears from my eyes. Paul squeezed my arm gently.

"I'll get some fresh water from the cistern," he said. While he was gone, Grandpère began to moan. I wiped my hands and went to him. His eyes were still closed, but he was muttering under his breath.

"It ain't right to blame me . . . ain't right. She was in love, wasn't she? What's the difference then? Tell me that. Go on," he said.

"Who was in love, Grandpère?" I asked.

"Go on, tell me what's the difference. You got somethin' against money, do you? Huh? Go on."

"Who was in love, Grandpère? What money?"

He moaned and turned over.

"What is it?" Paul said, returning with the water.

"He's talking in his sleep, but he doesn't make any sense," I said.

"That's easy to believe."

"I think . . . it had something to do with why he and my Grandmère Catherine are so angry at each other all the time."

"I don't think there's much of a mystery to that, Ruby. Look around; look at what he's become. Why should she want to have him in the house?" Paul said.

"No, Paul. It has to be something more. I wish he would tell me," I said, and knelt beside the cot. "Grandpère," I said, shaking his shoulder.

"Damn oil companies," he muttered. "Dredged the swamps and killed the three-cornered grass . . . killing the muskrats . . . nothin' for them to eat."

"Grandpère, who was in love? What money?" I demanded. He moaned and started to snore.

"No sense talking to him when he's like that, Ruby," Paul said.

I shook my head.

"It's the only time he might tell me the truth, Paul." I stood up, still looking down at him. "Neither he nor Grandmère Catherine will talk about it any other time."

Paul came to my side.

"I picked up a bit outside, but it will take a few days to get this place in shape," he commented.

"I know. We'd better start back. We'll dock his boat near my house. He'll pole the pirogue there tomorrow and find it."

"He'll find his head's got a tin drum inside it," Paul said. "That's what he'll find tomorrow."

We left the shack and got into the dingy. Neither of us spoke much on the way back. I sat beside Paul. He put his arm around me and I cradled my head against his shoulder. Owls hooted at us, snakes and gators slithered through the mud and water, frogs croaked, but my mind was fixed on Grandpère Jack's drunken words and I heard or saw nothing else until I felt Paul's lips on my forehead. He had shut off the motor and we were drifting toward the shore.

"Ruby," he whispered. "You feel so good in my arms. I wish I could hold you all the time, or at least have you in my arms whenever I wanted."

"You can, Paul," I replied softly, and turned my face to him so that he could bring his lips down to mine. Our kiss was soft, but long. We felt the boat hit the shore and stop, but neither of us made an attempt to rise. Instead, Paul wrapped his arms tighter around me and slipped down beside me, his lips now moving over my cheeks and gently caressing my closed eyes.

"I go to sleep every night with your kiss on my lips," Paul said.

"So do I, Paul."

His left arm pressed the side of my breast softly. I tingled and waited in excited anticipation. He brought his arm back slowly until his hand gently cupped my breast and his finger slipped over my throbbing, erected nipple beneath the thin cotton blouse and bra to undo the top buttons. I wanted him to touch me; I even longed for it, but the moment he did, my electric excitement was quickly followed by a stream of cold fear, for I felt how strongly I wanted him to do more, go further and kiss me in places so intimate, only I had touched or seen them. Despite his gentleness and his deep expressions of love, I could not get around Grandmère Catherine's dark eyes of warning looming in my memory.

"Wait, Paul," I said reluctantly. "We're going too fast."

"I'm sorry," Paul said quickly, and pulled himself back. "I didn't mean to. I just . . ."

"It's all right. If I don't stop you now, I won't stop you in a few minutes and I don't know what else we will do," I explained. Paul nodded and stood up. He helped me up and I straightened my skirt and blouse, rebuttoning the top two buttons. He helped me out of the boat and then pulled it up so it wouldn't be carried away when the tide from the Gulf raised the level of the water in the bayou. I took his hand and we made our way slowly back to the house. Grandmère Catherine was inside. We could hear her tinkering in the kitchen, finishing up the preparation of the biscuits she would bring to church in the morning.

"I'm sorry our celebration turned out this way," I said, and wondered how many more times I would apologize for Grandpère Jack.

"I wouldn't have missed a moment," Paul said. "As long as I was with you, Ruby."

"Is your family going to church in the morning?" He nodded. "Are you still coming to dinner tomorrow night?"

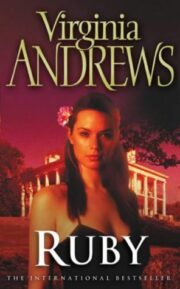

"Ruby" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Ruby". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Ruby" друзьям в соцсетях.