"I don't belong here. I don't have any mental or behavioral problems," I insisted.

"Perhaps not. Let me try something with you to see how you view the world around you, okay? Maybe that's all we'll do today and give you a chance to acclimate yourself to your surroundings more. No rush."

"Yes, there is a rush. I've got to go home."

"All right. We'll begin. I'm going to flash some shapes on the screen in front of you. I want you to tell me what comes to mind instantly when you see each one, okay? Don't think about them, just react as quickly as you can. That's easy, right?"

"I don't need to do this," I moaned.

"Just humor me then," he said, and snapped off the room light. He turned on the projector and put the first shape on the screen. "Please," he said. "The faster we do this, the faster you can relax."

Reluctantly, I responded.

"It looks like the head of an eel."

"An eel, good. And this?"

"Some kind of hose."

"Go on."

"A twisted sycamore limb . . . Spanish Moss . . . An alligator tail . . . A dead fish."

"Why dead?"

"It's not moving," I said.

He laughed. "Of course. And this?"

"A mother and a child."

"What's the child doing?"

"Breast-feeding."

"Yes."

He flashed a half-dozen more pictures and then put on the lights.

"Okay," he said, sitting across from me with his notebook. "I'm going to say a word and you respond immediately again, no thought. Just what comes first to mind, understand?" I just looked down. "Understand?" I nodded.

"Can't we just see Daphne and end this?"

"In due time," he said. "Lips."

"What?"

"What comes to mind first when I say, 'lips'?"

"A kiss."

"Hands."

"Work."

He recited a few dozen words at me, jotting down my reactions and then he sat back, nodding.

"Can I go home now?" I asked.

He smiled and stood up. "We have a few more tests to go through, some talking to do. It won't be too long, I promise. Since you have been cooperative, I'm going to permit you to go to the recreation area before lunch. Find something to read, something to do, and I'll see you again real soon, okay?"

"No, it's not okay," I said. "I want to call my daddy. Can I at least do that?"

"We don't permit patients to use the telephones."

"Will you call him, then? If you just call him, you'll see he doesn't want me to be here," I said.

"I'm sorry, Ruby, but he does," Doctor Cheryl said, and pulled a form out of the file. "See? Here is his signature," he said, and I looked at the line to which he pointed. Pierre Dumas was written there.

"She forged it, I'm sure," I said quickly. "She's going to tell him I ran away. Please, just call him. Will you do that?" He stood up without replying.

"You've got a little time before lunch. Get acquainted with the facilities. Try to relax. It will help us when we meet again," he said, td opened the door. The attendant was waiting. "Take her to the recreation room," Doctor Cheryl told him. The attendant nodded and looked in at me. Slowly, I rose.

"When my father finds out what she did and what you're doing, you're going to be in a lot of trouble," I threatened. He didn't reply and I had no choice but to follow the attendant back down the corridor to the recreation room.

"Hello, I'm Mrs. Whidden," a woman attendant no more than forty said, greeting me at the door. "Welcome. I'm here to help you. Is there something in particular you would like to do . . . handicrafts, perhaps?"

"No," I said.

"Well, why don't you just go about and look over every-thing until something strikes your fancy. Then I'll help you, okay?" she said. Seeing no point to my constantly protesting, I nodded and entered the room. I walked about, gazing at the patients, some of whom gazed at me with curiosity, some with what looked like anger, and some who didn't seem to see me. The redheaded boy who had been sitting doing nothing was still sitting that way. I noticed that his eyes followed me, however. I went to the window near him and gazed out, longing for my freedom.

"Hate being here?" I heard, and turned. It sounded like he had asked it, but he was still sitting stiffly, staring ahead.

"Did you ask me something?" I inquired. He didn't move, nor did he speak. I shrugged and looked out again, and again, I heard, "Hate being here?" I spun around.

"Pardon me?"

Still, without turning, he spoke again.

"I can tell you don't want to be here."

"I don't. I was kidnapped, locked up before I knew what was happening," I said. That animated his face to the point where he at least raised his eyebrows. He turned to me slowly, only his head moving, and he gazed at me with eyes that seemed as cold and as indifferent as eyes on a mannequin.

"What about your parents?" he asked.

"My father doesn't know what my stepmother has done. I'm sure," I said.

"What's the charge?"

"Pardon?"

"What's the reason you're supposedly here for? You know, your problem?"

"I'd rather not say. It's too embarrassing and ridiculous."

"Paranoia? Schizophrenia? Manic-depression? Am I getting warm?"

"No. Why are you here?" I demanded.

"Immobility," he declared. "I'm unable to make decisions, deal with responsibilities. When confronted with a problem, I simply become immobile. I can't even decide what I want to do in here," he added nonchalantly. "So I sit and wait for the recreation period to end."

"Why are you like this?" I asked. "I mean, you know what's wrong with you, apparently."

"Insecure." He smiled. "My mother, apparently like your stepmother, didn't want me. In her eighth month, she tried to abort me, but I only got born too soon instead. From then on, it was straight downhill: paranoia, autism, learning disabilities," he recited dryly.

"You don't seem like someone with learning disabilities," I said.

"I can't function in a normal school setting. I can't answer questions. I don't raise my hand, and when I'm given a test, I just stare at it. But I read," he added. "That's all I do. It's safe." He raised his eyes to me. "So why did they commit you? You don't have to be afraid of telling me. I won't tell anyone else. But I don't blame you if you don't trust me," he added quickly.

I sighed.

"I've been accused of being too loose with my sexual activities," I said.

"Nymphomania. Great. We don't have any of those." I couldn't help but laugh.

"You still don't," I said. "It's a lie."

"That's all right. This place flourishes on lies. Patients lie to each other, to themselves, and to the doctors and the doctors lie because they claim they can help you, but they can't. All they can do is keep you comfortable," he said bitterly. He lifted his rust-colored eyes toward me again. "You can tell me your real name or you can lie, if you want."

"My name's Ruby, Ruby Dumas. I know your first name is Lyle, but I forgot your last name."

"Black. Like the bottom of an empty well. Dumas," he said. "Dumas. There's someone else here with that name."

"My uncle," I said. "Jean. I was brought here supposedly to visit him."

"Oh. You're Jean's niece?"

"But I never got to see him."

"I like Jean."

"Does he talk to you? What's he like? How is he?" I hurriedly asked.

"He doesn't talk to anyone, but that doesn't mean he can't. I know he can. He's . . . just very quiet, but as gentle as a little boy and as frightened sometimes. Sometimes, he cries for what seems to be no reason, but I know something's going on in his head to make him cry. Occasionally, I catch him laughing to himself. He won't tell anyone anything, especially the doctors and nurses."

"If I can only see him. At least that would be something good," I said.

"You can. I'm sure he’ll be at lunch in the little cafeteria." "I've never met him before," I said. "Will you point him out to me?"

"Not hard to do. He's the best-dressed and the best-looking guy here. Ruby, huh? Nice," he said, and then tightened his face as if he had said something terrible.

"Thank you." I paused and looked around. "I don't know what I'm going to do now. I've got to get out of here, but this place is worse than a prison—doors that have to be buzzed open, bars on the windows, attendants everywhere . . ."

"Oh, I can get you out," he said casually. "If that's what you really want."

"You can? How?"

"There's a room that has a window without bars on it, the laundry room."

"Really? But how can I get to it?"

"I'll show you . . . later. They let us go outside if we want after lunch and there's a way into the laundry room from the yard."

My heart lifted with hope.

"How do you know all this?"

"I know everything about this place," he replied.

"You do? How long have you been here?" I asked.

"Since I was seven," he said. "Ten years."

"Ten years! Don't you ever want to leave?" I asked. He stared ahead for a moment. A tear escaped his right eye and slid down his cheek.

"No," he said. He turned to me with the saddest eyes. "I belong here. I told you," he continued, "I can't make a decision. I told you I'd help you, but later, when it comes time to do it, I don't know if I can." He stared ahead. "I don't know if I can."

My brightened spirits darkened again when I realized he might just be doing what he said everyone did here—lying.

A bell was rung and Mrs. Whidden announced it was time to go to lunch. I brightened again. At least now, I would see Uncle Jean. Unless of course, that was a lie, too.

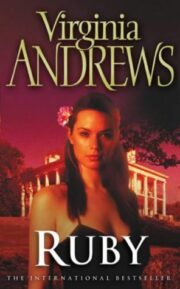

21

Betrayed Again

"Ruby" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Ruby". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Ruby" друзьям в соцсетях.