"Don't blame yourself," Lyle said, "something like that usually happens."

Lyle continued to eat a little more of his stew, but I couldn't put anything in my mouth. I felt so sick inside, so empty and defeated. I had to get out of here; I just had to.

"What happens now?" I asked him. "What will they do to him?"

"Just take him to his room. He usually calms down after that."

"What happens with us after lunch?"

"They'll take us out for a while, but the area is fenced in, so don't think you can just run off."

"Will you show me how to escape then? Will you, Lyle? Please," I begged.

"I don't know. Yes," he said. Then a moment later he said, "I don't know. Don't keep asking me."

"All right, Lyle. I won't," I said quickly. He calmed down and started on his dessert.

Just as he had said, when the lunch hour ended, the attendants directed the patients to their outside time. On my way out with Lyle, the head nurse, Mrs. McDonald, approached me.

"Dr. Cheryl has you scheduled for another hour of evaluation late this afternoon," she said. "I will come for you when it's time. How are you getting along? Make any friends?" she asked, eying Lyle who walked a step or two behind me. I didn't respond. "Hello, Lyle. How are you today?"

"I don't know," he said quickly.

Mrs. McDonald smiled at me and walked on to speak to some other patients.

The yard didn't look much different from the grounds in front of the institution. Like the front, the back had walk-ways and benches, fountains and flower beds with sprawling magnolia and oak trees providing pools of shade. There was an actual pool for fish and frogs, too. The grounds were obviously well maintained. The rock gardens, blossoms, and polished benches glittered in the warm, afternoon sunlight

"It's very nice out here," I reluctantly admitted to Lyle.

"They've got to keep it nice. Everyone here comes from a wealthy family. They want to be sure the money continues to flow into the institution. You should see this place when they schedule one of their fêtes for the families of patients. Every inch is spick-and-span, not a weed, not a speck of dust, and not a face without a smile," he said, smirking.

"You sound very critical of them, Lyle, yet you want to stay. Why don't you think about trying life on the outside again? You're much brighter than most boys I've met," I said. He blanched but looked away.

"I'm not ready yet," he replied. "But I can tell just from the short time I've been with you that you definitely don't belong here."

"I've got another session scheduled with Dr. Cheryl. He's going to find a way to keep me. I just know it," I moaned. "Daphne gives this place too much money for him not to do what she wants." I embraced myself and looked down as we walked along. Around us and even behind us, the attendants watched.

"You go ask to go to the bathroom," Lyle suddenly said. "It's right off the rear entrance. They won't bother you. To the left of the rest room is a short stairway which goes down to the basement. The second door on the right is the laundry room. They've already done their laundry work for today. They do it in the morning. So there won't be anyone there."

"Are you sure?"

"I told you, I've been here ten years. I know which clocks run slow and which run fast, what door hinges squeak, and where there are windows without bars on them," he added.

"Thank you Lyle."

He shrugged.

"I haven't done anything yet," he said, as if he wanted to convince himself more than me that he hadn't made a decision.

"You've given me hope, Lyle. That's doing a great deal." I smiled at him. He stared at me a moment, his rust-colored eyes blinking and then he turned away.

"Go on," he said. "Do what I told you."

I went to the female attendant and explained that I had to go to the bathroom.

"I'll show you where it is," she said when we returned to the door.

"1 know where it is. Thank you," I replied quickly. She shrugged and left me. I did exactly what Lyle said and scurried down the short flight of steps. The laundry room was a large, long room with cement floors and cement walls lined with washing machines, dryers, and bins. Toward the rear were the windows Lyle had described, but they were high up.

"Quick," I heard him say as he entered behind me. We hurried to the back. "You just snap the hinge in the middle and slide the window to your left," he whispered. "It's not locked."

"How do you know that, Lyle?" I asked suspiciously. He looked down and then up at me quickly.

"I've been here a few times. I even went so far as to stick my foot out, but I . . . I'm not ready," he concluded.

"I hope you will be ready soon, Lyle."

"I'll give you a boost up. Come on, before we're missed," he said, cupping his hands together for my foot.

"I wish you would come with me, Lyle," I said, and put my foot into his hands. He lifted and I clutched at the windowsill to pull myself up. Just as he described, the latch opened easily and I slid the window to the left. I looked down at him.

"Go on," he coached.

"Thank you, Lyle. I know how hard it was for you to do this."

"No it wasn't," he confessed. "I wanted to help you. Go on."

I started to crawl through the window, looking around as I did so to be sure no one was nearby. Across the lawn was a small patch of trees and beyond that, the main highway. Once I was out, I turned and looked back in at him.

"Do you know where to go from here?" he asked me.

"No, but I just want to get away."

"Go south. There's a bus stop there and the bus will take you back to New Orleans. Here," he said, digging into his pants pocket and coming up with a fistful of money. "I don't need this in here."

He handed me the bills.

"Thank you, Lyle."

"Be careful. Don't look suspicious. Smile at people. Act like you're just on an afternoon outing," he advised, telling me things I was sure he had recited to himself a hundred times in vain.

"I'll be back to visit you someday, Lyle. I promise. Unless you're out before then. If you are, call me."

"I haven't used a telephone since I was six years old," he admitted. Looking down at him in the laundry room, I felt so sorry for him. He seemed small and alone now, trapped by his own insecurities. "But," he added, smiling, "if I do get out, I'll call you."

"Good."

"Get going . . . quickly," he said. "Remember, look natural."

He turned and walked away. I stood up, took a deep breath, and started away from the building. When I was no more than a dozen or so feet from it, I looked back and caught sight of someone on the third floor standing in the window. A cloud moved over the sun and the subsequent shade made it possible for me to see beyond the glint of the glass.

It was Uncle Jean!

He looked down at me and then raised his hand slowly. I could just make out the smile on his face. I waved back and then I turned and ran as hard and as fast as I could for the trees, not looking back until I had arrived. The building and the grounds behind me remained calm. I heard no shouting, saw no one running after me. I had slipped away, thanks to Lyle. I focused one more time on the window of Uncle Jean's room, but I couldn't see him anymore. Then I turned and marched through the woods to the highway.

I went south as Lyle had directed and reached the bus station which was just a small quick stop with gas pumps, candies and cakes, homemade pralines and soda. Fortunately, I had to wait only twenty minutes for the next bus to New Orleans. I bought my ticket from the young lady behind the counter and waited inside the store, thumbing through magazines and finally buying one just so I wouldn't be visible outside in case the institute had discovered I was missing and had sent someone looking for me.

I breathed relief when the bus arrived on time. I got on quickly, but following Lyle's advice, I acted as calmly and innocently as I could. I took my seat and sat back with my magazine. Moments later, the bus continued on its journey to New Orleans. We went right past the main entrance of the institution. When it was well behind us, I let out a breath. I was so happy to be free, I couldn't help but cry. Afraid someone would notice, I wiped away my tears quickly and closed my eyes and suddenly thought about Uncle Jean stuttering, "Jib . . . jib . . ."

The rhythm of the tires on the macadam highway beat out the same chant: "Jib . . . jib . . . jib."

What was he trying to tell me? I wondered.

When the New Orleans' skyline came into view, I actually considered not returning to my home and instead returning to the bayou. I wasn't looking forward to the greeting I would receive from Daphne, but then some of Grandmère Catherine's Cajun pride found its way into my backbone and I sat up straight and determined. After all, my father did love me. I was a Dumas and I did belong with him, too. Daphne had no right to do the things she had done to me.

By the time I got on the right city bus and then changed for the streetcar and arrived at the house, I was sure Dr. Cheryl had called Daphne and informed her I was missing. That was confirmed for me the moment Edgar greeted me at the door and I took one look at his face.

"Madame Dumas is waiting for you," he said, shifting his eyes to indicate all was not well. "She's in the parlor." "Where's my father, Edgar?" I demanded.

He shook his head first and then he replied in a softer voice, "Upstairs, mademoiselle."

"Inform Madame Dumas that I've gone up to see him first," I ordered. Edgar widened his eyes, surprised at my insubordination.

"No, you're not!" Daphne shouted from the parlor doorway the moment I stepped into the entryway. "You're marching yourself right in here first." She stood there, her arm extended, pointing to the room. Her voice was cold, commanding. Edgar quickly moved away and retreated through the door that would take him through the dining room and into the kitchen, where I was sure he would make a report to Nina.

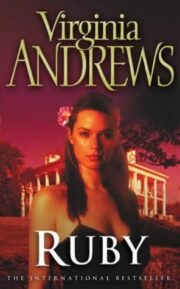

"Ruby" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Ruby". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Ruby" друзьям в соцсетях.