Sunlight wove its way through the leaves of the cypress and sycamores around the house and filtered through the cloth over my window to cast a warm, bright glow over my small bedroom which had just enough space for my white painted bed, a small stand for a lamp near the pillow, and a large chest for my clothing. A chorus of rice birds began their ritual symphony, chirping and singing, urging me to get up, get washed, and get dressed so I could join them in the celebration of a new day.

No matter how I tried, I never beat Grandmère Catherine out of bed and into the kitchen. Rarely did I have the opportunity to surprise her with a pot of freshly brewed coffee, hot biscuits, and eggs. She was usually up with the first rays of sunlight that began to push back the blanket of darkness, and she moved so quietly and so gracefully through the house that I didn't hear her footsteps in the hallway or down the stairs, which usually creaked loudly when I descended. Weekend mornings Grandmère Catherine was up especially early so as to prepare everything for our roadside stall.

I hurried down to join her.

"Why didn't you wake me?" I asked.

"I'd wake you when I needed you if you didn't get yourself up, Ruby," she said, answering me the same way she always did. But I knew she would rather take on extra work than shake me out of the arms of sleep.

"I'll fold all the new blankets and get them ready to take out," I said.

"First, you'll have some breakfast. There's time enough for us to get things out. You know the tourists don't come riding by for a good while yet. The only ones who get up this early are the fishermen and they're not interested in anything we have to sell. Go on now, sit down," Grandmère Catherine commanded.

We had a simple table made from the same wide cypress planks from which our house walls were constructed, as were the chairs with their grooved posts. The one piece of furniture Grandmère was most proud of was her oak armoire. Her father had made it. Everything else we had was ordinary and no different from anything every other Cajun family living along the bayou possessed.

"Mr. Rodrigues brought over that basket of fresh eggs this morning," Grandmère Catherine said, nodding toward the basket on the counter by the window. "Very nice of him to think of us during his troubled times."

She never expected much more than a simple thank-you for any of the wonders she worked. She didn't think of her gifts as being hers; she thought of them as belonging to the Cajun people. She believed she was put on this earth to serve and to help those less fortunate, and the joy of helping others was reward enough.

She began to fry me two eggs to go along with her biscuits. "Don't forget to put out your newest pictures today. I love the one with the heron coming out of the water," she said, smiling.

"If you love it, Grandmère, I shouldn't sell it. I should give it to you."

"Nonsense, child. I want everyone to see your pictures, especially people in New Orleans," she declared. She had said that many times before and just as firmly.

"Why? Why are those people so important?" I asked.

"There's dozens and dozens of art galleries there and famous artists, too, who will see your work and spread your name so that all the rich Creoles will want one of your paintings in their homes," she explained.

I shook my head. It wasn't like her to want fame and notoriety brought to our simple bayou home. We put out our handicrafts and wares to sell on weekends because it brought us the necessary income to survive, but I knew Grandmère Catherine wasn't comfortable with all these strangers coming around, even though some of them loved her food and piled compliments at her feet. There was something else, some other reason why Grandmère Catherine was pushing me to exhibit my artwork, some mysterious reason.

The picture of the heron was special to me, too. I had been standing on the shore by the pond behind our house at twilight one day when I saw this grosbeak, a night heron, lift itself from the water so suddenly and so unexpectedly, it did seem to come out of the water. It floated up on its wide, dark purple wings and soared over the cypress. I felt something poetic and beautiful in its movements and couldn't wait to capture some of that in a painting. Later, when Grandmère Catherine set her eyes on the finished work, she was speechless for a moment. Her eyes glistened with tears and she confessed that my mother had favored the blue heron over all the other marsh birds.

"That's more reason for us to keep it," I said.

But Grandmère Catherine disagreed and said, "More reason for us to see it carried off to New Orleans." It was almost as if she were sending some sort of cryptic message to someone in New Orleans through my artwork.

After I ate my breakfast, I began to take out the handicrafts and goods we would try to sell that day, while Grandmère Catherine finished making the roux. It was one of the first things a young Cajun girl learned to make. Roux was simply flour browned in butter, oil, or animal fat and cooked to a nutty brown shade without letting it turn so hot that it burned black. After it was prepared, seafood or chicken, sometimes duck, goose, or guinea hen, and some-times wild game with sausage or oysters was mixed in to make the gumbo. During Lent Grandmère made a green gumbo that was roux mixed only with vegetables rather than meat.

Grandmère was right. We began to get customers much earlier than we usually did. Some of the people who dropped by were friends of hers or other Cajun folk who had learned about the couchemal and wanted to hear Grandmère tell the story. A few of her older friends sat around and recalled similar tales they had heard from their parents and grandparents.

Just before noon, we were surprised to see a silver gray limousine, fancy and long, going by. Suddenly, it came to an abrupt stop and was then backed up very quickly until it stopped again in front of our stall. The rear door was thrown open and a tall, lanky, olive-skinned man with gray-brown hair stepped out, the laughter of a woman lingering behind him within the limousine.

"Quiet down," he said, then turned and smiled at me.

An attractive blond lady with heavily made-up eyes, thick rouge, and gobs of lipstick, poked her head out the open door. A long pearl necklace dangled from her neck. She wore a blouse of bright pink silk. The first several buttons were not done so I couldn't help but notice that her breasts were quite exposed.

"Hurry up, Dominique. I expect to have dinner at Arnaud's tonight," she cried petulantly.

"Relax. We'll have plenty of time," he said without looking back at her. His attention was fixed on my paintings. "Who did these?" he demanded.

"I did, sir," I said. He was dressed expensively in a white shirt of the snowiest, softest-looking cotton and a beautifully tailored suit in dark charcoal gray.

"Really?"

I nodded and he stepped closer to take the picture of the heron into his hands. He held it at arm's length and nodded. "You have instinct," he said. "Still primitive, but rather remarkable. Did you take any lessons?"

"Just a little at school and what I learned from reading some old art magazines," I replied.

"Remarkable."

"Dominique!"

"Hold your water, will you." He smirked at me again as if to say, "Don't mind her," and then he looked at two more of my paintings. I had five out for sale. "How much are you asking for your paintings?" he asked.

I looked at Grandmère Catherine who was standing with Mrs. Thibodeau, their conversation on hold while the limousine remained. Grandmère Catherine had a strange look in her eyes. She was peering as though she were looking deeply into this handsome, well-to-do stranger, searching for something that would tell her he was more than a simple tourist amusing himself with local color.

"I'm asking five dollars apiece," I said.

"Five dollars!" He laughed. "Firstly, you shouldn't ask the same amount for each," he lectured. "This one, the heron, obviously took more work. It's five times the painting the others are," he declared assuredly, turning to address Grandmère Catherine and Mrs. Thibodeau as if they were his students. He turned back to me. "Why, look at the detail . . . the way you've captured the water and the movement in the heron's wings." His eyes narrowed and he pursed his lips as he looked at the paintings and nodded to himself. "I'll give you fifty dollars for the five of them as a down payment," he announced.

"Fifty dollars, but—"

"What do you mean, as a down payment?" Grandmère Catherine asked, stepping toward us.

"Oh, I’m sorry," the gentleman said. "I should have introduced myself properly. My name is Dominique LeGrand. I own an art gallery in the French Quarter, simply called Dominique's. Here," he said, reaching in and taking a business card from a pocket in his pants. Grandmère took the card and pinched it between her small fingers to look at it.

"And this . . . down payment?"

"I think I can get a good deal more for these paintings. Usually, I just take an artist's work into the gallery without paying anything, but I want to do something to show my appreciation of this young girl's work. Is she your granddaughter?" Dominique inquired.

"Yes," Grandmère Catherine said. "Ruby Landry. Will you be sure her name is shown along with the paintings?" she asked, surprising me.

"Of course," Dominique LeGrand said, smiling. "I see she has her initials on the corner," he said, then turned to me. "But in the future, put your full name there," he instructed. "And I do believe there is a future for you, Mademoiselle Ruby." He took a wad of money from his pocket and peeled off fifty dollars, more money than I had made selling all my paintings up until now. I looked at Grandmère Catherine who nodded and then I took the money.

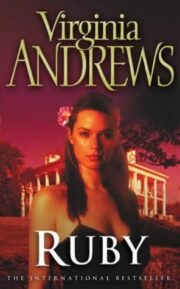

"Ruby" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Ruby". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Ruby" друзьям в соцсетях.