Jolted out of his trance, the newcomer recollected his purpose. “He does, Goodman Malte, and His Grace bade me give you this.” Reaching into an inner pocket in his doublet, he withdrew a letter bearing the royal seal.

Bridget and I stayed where we were, our eyes fixed on the stranger. He was younger than Father, but he still seemed quite old to me. He had a very fine brown beard and mild gray eyes.

“Who is he?” I whispered to my sister as Father read the king’s message.

“He must be Anthony Denny, a yeoman of the wardrobe and a groom of the king’s privy chamber.”

That sounded very important, although no more so than “royal tailor.” I was too young yet to grasp the difference between a gentleman born and a merchant whose wealth allowed him to rise into the ranks of the gentry.

When Father finished reading he tossed the missive into the fire burning in the hearth. “We will set out on the morrow,” he promised.

“Is this the lass?” Master Denny jerked his head in my direction.

Bridget, sitting next to me on one of the long workroom tables, assumed he meant her and preened.

“Yes,” Father said. “Audrey, come and make your curtsey to Master Denny.”

I heard Bridget squeak in outrage as I hopped down to obey. She’d come to expect the admiration of males of all ages and was not accustomed to being relegated to second place.

“Tomorrow, Audrey,” Father said, “at King Henry’s request, you will accompany me to court.”

My heart began to beat a little faster. “To court?”

He nodded. “Go along with you now. You and Bridget both. I must speak further of this matter with Master Denny.”

Bridget held her tongue only until we reached the hall on the floor above, the central chamber of our living quarters. Another goodly blaze crackled in that fireplace, sending out waves of welcome warmth and the soothing smell of burning applewood.

“Why were you chosen to visit the king when I am older?”

“How am I to know? Ask Father.”

Bridget pinched my arm hard enough to leave a bruise before turning to the eldest of our sisters. “Elizabeth! Audrey is to go to court with Father! It should have been me!”

Elizabeth glanced up from her embroidery, a puzzled expression on her plump-cheeked face. “Why would either of you want to go to court?” She was nearly fifteen and soon to marry. She cared for little beyond making plans for the household and servants she would have after she wed.

Muriel sat beside Elizabeth on the low settle, all her concentration fixed on the small, even stitches she was using to hem a linen shirt. She had the same yellow hair as Bridget but none of her vivacity. Muriel’s idea of an entertaining afternoon was one spent in the garden feeding bread crumbs to the birds.

“Everyone wants to go to court to see the king!” The exasperation in Bridget’s voice made her opinion clear—if Elizabeth had possessed even a grain of sense, she would never have had to ask.

I said nothing. Although I had not thought of the incident for years, Bridget’s words brought back to me the last occasion upon which I had seen King Henry. At the time, he had frightened me half to death with his booming voice. In hindsight, I realized that he had very likely saved my life.

“It is not fair,” Bridget wailed.

“There is no call to raise your voices,” Mother Anne admonished her, entering the hall from the gallery that crossed over the yard from the countinghouse above the kitchen. “What is all this to-do about?”

Our town house, a tall, sturdy structure made of wood and Flemish wall, was so large and commodious that both a warehouse and a kitchen opened off the cobblestone-paved courtyard at the back of the shop. The family sleeping chambers were above the hall—Elizabeth, Bridget, Muriel, and I shared a room. The apprentices slept in the garret at the very top of the house.

Bridget was only too willing to repeat her complaints for Mother Anne’s benefit.

“Bridget can go in my place,” I offered. “No one will know the difference.”

Mother Anne shook her head. She was a round little dumpling of a woman, good-natured and affectionate, but she could take a firm stand when one was needed. “I very much fear, sweetings, that the king can tell the difference between a redheaded girl and one with yellow curls. You will do as your father tells you, Audrey, and we will none of us mention Bridget’s complaints to him. As for you, Bridget, remember that envy is a sin. Do not allow yourself to fall prey to it.”

4

March 1538

It was still early spring, with a chill in the air. Father bundled me into a warm cloak for the trip upriver to the king’s great palace of Whitehall, in the city of Westminster. We went by boat, embarking from the stairs at Paul’s Wharf.

Father assisted me into the small watercraft he’d waved ashore and indicated that I should sit on one of the embroidered cushions. I watched him closely as he settled in beside me. He did not seem at all nervous about venturing out onto the Thames. I was less sanguine, viewing the choppy water with darkest suspicion. It was a dirty brown in color and there were objects floating in it. I did not want to look too closely at any of them, for I suspected that at least a few were the carcasses of dead animals. I will not even attempt to describe the foul stench that wafted up from beneath the surface.

The waterman extended one grimy hand in our direction while using the other to hold his boat steady. Father gave him a threepenny piece. This seemed extravagant to me. Mother Anne had taught all of her daughters to be frugal with household expenses. Threepence was sufficient to purchase a half-dozen silk points. Two of the small silver coins would have bought a whole pig.

The oars creaked in their locks as the waterman bent to his work and we made good speed upriver on an incoming tide. We did not have far to go, and to make the journey pass even more swiftly, Father pointed out the sights along the way. They were all new to me. Since the day John Malte first took me home with him, I had not once ventured beyond London’s city walls. Even within them, I had rarely gone farther from Watling Street than the shops of Cheapside.

The south bank of the Thames was largely open countryside. We could see across it to the Archbishop of Canterbury’s palace, rising up in distant Lambeth. On the London side, we first passed Blackfriars. Once a great religious house, it had in more recent years been carved up into residences for wealthy pensioners and minor lords.

“Many great noblemen have houses along this stretch of the river,” Father said. “The road that runs from Ludgate to the city of Westminster is called the Strand. We might have ridden along it to our destination, but then we would not have been able to enjoy the best view.”

I agreed that the riverside houses were indeed magnificent. Most had terraces and gardens that ran all the way down to the Thames. Many had their own water gates and landing stairs, too.

The river itself was crowded with every sort of watercraft, from small hired boats like our own to magnificent private barges. Sturdy commercial vessels carried goods downriver for sale in London or export to foreign lands. We made steady progress in spite of the traffic, traveling much faster than if we’d taken the land route. In the Strand, pedestrians, carts, and wagons prevent those on horseback from any better pace than a slow walk.

“Look,” Father instructed as we rounded the bend in the river. I gasped with pleasure as I beheld the gleaming towers of Whitehall, the king’s palace at Westminster. The waterman put his back into his work and guided the boat to the water stairs Father indicated.

A liveried sergeant porter inspected us before we were allowed to pass into the king’s privy garden. He knew Father on sight but he gave me an odd look. I paid him no mind. I was too entranced by my surroundings.

March is not the most beautiful time of year in any garden, but the topiary work and the greenery in the raised beds were very fine. There were gardeners busy everywhere I looked. Some were planting. Others were digging a large, deep hole.

“That will be a pond for the swans,” Father said. “When it is finished it will be bounded by hedges secured to latticework.”

Overlooking the gardens were galleries. Through their large windows I glimpsed courtiers walking back and forth for exercise. I was too far away to make out their faces. It did not occur to me until much later that they could see me as well as I could see them.

We walked along the graveled paths, in no apparent hurry to enter the palace. I wondered at that, and plied Father with questions, but he just shook his head and counseled patience.

The sound of the workmen’s shovels digging into sodden earth seemed loud in the silence that fell between us. In the distance I heard a boatman shout, “Eastward, ho!” And then, without warning, came a strange racket, half bark and half bay. It filled the air, heralding the appearance of a pack of dogs.

They burst out of the shrubbery only a few feet in front of me, tumbling one over another in eager play. I would have been terrified had they been deerhounds, or even terriers, but these dogs belonged to a breed I had never seen before. They were tiny, the largest no more than five inches in height at the shoulder. I counted eight in all.

First one pup, then another, caught sight of me and bounded my way. Then two veered off and began to tussle with each other. The first one bit the second’s ear. Then that pup went for the first dog’s tail. A third, the smallest of the lot, his fur a motley white, red, lemon, and orange-brown, lost interest in me and raced back to join the fun. All three rolled off the graveled path and into the hole the men had been digging.

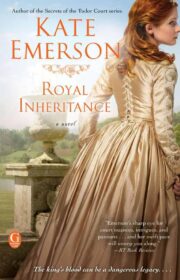

"Royal Inheritance" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Royal Inheritance". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Royal Inheritance" друзьям в соцсетях.