The next part of my memory is a blur. I suppose I must have traveled for some distance through narrow passages and down even narrower flights of stairs. Windsor Castle is a great, sprawling place. It would not have taken long for me to become hopelessly lost. I ended up huddled in an alcove in a drafty and deserted corridor, sitting on the cold, flagged floor with my knees drawn up to my chest. Seeking warmth as well as comfort, I wrapped my arms around them and cried my heart out, never imagining that anyone was near enough to overhear me.

All my focus was centered on the way my cheek stung and how badly my bruised ribs ached every time I drew in a deep breath. Although sobbing increased the pain, I could not seem to stop. I was so lost to my distress that I was unaware of the approach of a company of men until one of them stopped and spoke to me.

The sound of his loud, deep voice terrified me. With one last hiccough, I fell silent and tried to make myself even smaller. I did not dare look up at the man who’d addressed me. I was braced for a blow.

After a moment, a gloved finger adorned with a gold ring set with a large ruby appeared before my eyes. It came to rest under my chin and raised it until I was forced to look upon his face. His eyes, blue-gray in color, widened when he got his first clear view of my features.

I must have been a pitiful sight, an ungainly child with scraggly red locks and a tearstained face, but he shifted his hand to lift a strand of that hair and, after a moment, used an exquisitely gentle touch to caress my bruised cheek.

He asked me my name, and that of my mother, though perhaps not in that order.

He was a big man, tall and strong, and he wore the most splendid garments I had ever seen. They were made of rich fabrics and studded with precious gems. A heavy gold collar hung round his neck and the faint smell of musk and rosewater clung to his person. Beneath a very fine bonnet, he had hair as red as my own.

The gentlemen who accompanied him were also richly dressed. One of them wore the distinctive vestments and tall hat of a bishop. They all stared at me. Time seemed to stretch out, although I’ve no doubt that only a few moments passed. Then the red-haired man barked an order and all but one of his party moved on.

A yeoman of the guard remained behind, resplendent in scarlet livery with the royal badge, a rose, embroidered on his breast. He took a firm grip on my arm and led me away in the opposite direction. I expected to be taken back to Dobson’s lodgings. Instead he delivered me to a chamber that had been set aside as a workroom for the king’s tailor.

Orders had been given, although I was unaware of them at the time. I was to be clothed and looked after until such time as arrangements could be made for me. The king—for that bejeweled and gentle red-haired man had been no other than King Henry the Eighth himself—had taken exception to my mistreatment by my mother’s husband.

I was taken from my mother and given into the keeping of the king’s tailor, one John Malte by name, and his wife, Anne. Malte was a little man, lean and wiry, with straw-colored hair and sympathetic blue eyes and freckles that danced across the nose and cheeks of a clean-shaven face. His speech was slow and measured—he was wont to choose all his words with care—and even before he knew who I was, he treated me with kindness and consideration. When I fell asleep on a padded bench in his workroom, he covered me with a length of expensive damask.

Many years passed before I learned what transpired while I slept. At the time, I knew only what I was told when I awoke. John Malte took my small hand in his bigger, callused one and informed me that I was to come home with him to London. From that day forward, he said, my name was Audrey Malte.

3

I settled happily into my new life and soon forgot the old. Home was a tall house in Watling Street in London in the parish of St. Augustine by Paul’s Gate. The entire parish stood in the shadow of St. Paul’s.

I shared this house with Mother Anne, Father’s second wife, with her daughter by her first marriage, and with the two daughters Father’s first wife had given him before she died. Elizabeth, at nine, was five years my senior. Bridget was six when I arrived and old enough to resent the addition of yet another sister. Muriel, at age five, welcomed a new playmate.

Time passed.

When I was eight, Father explained my origins to me. He had, he said, begotten me on my mother during one of his many visits to Windsor Castle in the king’s service. I was, he said, a merry-begot, for there had been much joy in my making. I thought this a much nicer word than baseborn or illegitimate or bastard.

In the greater world, the king had married Anne Boleyn, Lady Marquess of Pembroke, and they’d had a daughter, Princess Elizabeth. And then he had divorced and beheaded Queen Anne. When he took another English gentlewoman to wife—Mistress Jane Seymour—she gave birth to a son, a prince who would later ascend the throne as King Edward VI. Then Queen Jane died. That was during the autumn following my ninth birthday.

Father was summoned to court to make mourning garments for the king. Kings wear purple for mourning, but everyone else must dress in black. After Candlemas, the second day of February, courtiers were permitted to resume their normal attire. Father was inundated with orders for new clothes. He worked late into the night and his apprentices with him, squinting in the candlelight to see what they were stitching.

From the beginning, I spent many happy hours in the tailor shop that occupied the large single room on the ground floor of the Watling Street house. A stairway led down to it from the living quarters above, giving me easy access. On occasion, Mother Anne dispatched me with messages for Father. More often, I visited because my sister Bridget persuaded me to go with her. She liked to watch the apprentices work. At eleven, Bridget was already showing signs of budding womanhood. The apprentices liked to watch her, too.

Father customarily set the boys to performing various tasks appropriate to their skill. Since the fabrics he worked with were valuable and not to be cut into lightly, he personally oversaw the laying out of paper patterns traced from buckram pieces onto luxurious fabrics as varied as satin, damask, and cloth of silver.

“Match the grain lines and make certain that the pile runs in the same direction,” he warned. “And the woven designs must be balanced.”

More important still, the pattern pieces had to be arranged so that there was as little waste as possible. Once Father approved the placement of the pattern pieces, he used tailor’s chalk to mark the pattern lines on silk or wool camlet, and even on cloth of gold, but on velvet it was necessary to trace-tack the pattern pieces instead.

Bridget wound a lock of long, pale yellow hair around her finger while she watched two of the apprentices outline each shape with thread. When they were done and Father had checked their stitches, he supervised the removal of the pattern pieces. These were made of stiff brown paper. Father kept them until they wore out, adjusting them to use for more than one person.

In addition to making clothes for the king, Father also had many private clients, women as well as men. They paid him well for his services, allowing us to live in considerable luxury. He had even made a few garments for Queen Anne and for Queen Jane, although it was our neighbor in Watling Street, John Scutt, who held the post of queen’s tailor. Poor Master Scutt lost his wife at about the same time Queen Jane died. Like the queen, she did not survive childbirth. She left her husband with a baby girl he named Margaret.

“I want to help with the cutting,” I announced on this particular day. I was already reaching for Father’s best pair of shears when he stopped me.

“This length of cloth, uncut, must first be sent to the embroiderers. There it will be stretched taut on a frame and they will use our shapes to guide them. See there? All the seam lines are clearly marked. And from the shape, the embroiderers will know whether they are stitching on the front or the back of the garment.”

“And then may I cut it?”

“Then I will cut it. Or Richard will. And afterward, we will make this length of velvet into clothing, with suitable linings and interlinings.”

Richard Egleston was one of Father’s former apprentices. When he finished his training, he married another of Father’s daughters, Mary, the child of his first wife by her first husband, and stayed on in the shop as a cutter.

“I would do a most excellent job for you, Father.” Eager to prove my worth, I persisted in trying to convince him. It had not yet been impressed upon me that girls could not be apprenticed as tailors, or indeed in any other trade.

“You have not had the necessary training to work with such expensive cloth.”

“I can sew,” I argued. “Mother Anne taught me.”

What Father might have said to that, I do not know, for at that precise moment a gentleman entered the shop. I had never seen him before, but I could tell he was a courtier by the way he was dressed. Beneath a fur-lined cloak with the king’s badge on the shoulder he wore the black livery that marked him as a member of the royal household.

He blinked upon first coming inside out of the sunlight. Then his gaze fell upon me. Whatever he had been about to say seemed to fly out of his head. He stood there, silent and staring, until Father spoke to him.

“How may I serve you, Master Denny?” Father’s voice sounded a trifle sharper than usual. “Does His Grace the King require my presence at court?”

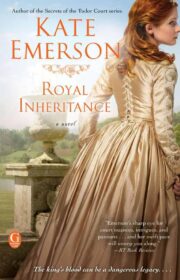

"Royal Inheritance" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Royal Inheritance". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Royal Inheritance" друзьям в соцсетях.