Audrey Harington spent a moment longer staring at the view from an upper window in the mansion that had been her husband’s town house for the last six years. It was the finest residence in Stepney, barring only the nearby Bishop of London’s palace. The house even boasted its own private chapel, in spite of the fact that it took only a few minutes to walk to the church of St. Dunstan, where everyone in the household went for services on Sundays and holy days.

From her vantage point, Audrey had an unobstructed view across more than a mile of flat fields and marshes to the most terrifying place in all of England—the Tower of London. Its stone walls rose to formidable heights, easily visible even at this distance. An involuntary shudder passed through her at the thought of all the poor souls held prisoner there, some of them for no more than a careless word. Some would eventually be set free. Others would be executed. Their fate would depend less upon guilt or innocence than upon the whim of Queen Mary and her Spanish husband, King Philip.

Shaking off these melancholy thoughts, since brooding about injustice would never accomplish anything, Audrey turned to address a situation she could remedy. Hester, her eight-year-old daughter, squirmed in the high-backed chair in which Master Eworth had posed her. It was well padded with red velvet cushions, but any position grew uncomfortable with the passage of time. The book Eworth had provided as a prop might have held her attention had she been able to read it, but it was written in Latin. The slim, leather-bound volume lay abandoned, stuffed into the space between Hester’s thigh and the seat of the chair, and in imminent danger of tumbling to the floor.

“Let me see what I can do.”

Audrey spoke in a genteel and well-modulated voice and rose smoothly from the window seat. That simple act, executed too quickly, was enough to betray her weakness. The first moment of dizziness was as debilitating as a blow to the head. The sensation did not last long, but by the time she recovered her equilibrium, warmth had flooded into her face. She needed no looking glass to know that hectic spots of color dotted her cheeks.

As Audrey glided past Master Eworth, she avoided meeting his gaze. He saw too much. His artist’s eye was keen and she feared he had already noticed how greatly she had changed since he had painted her portrait the previous year. She had been exceeding ill of a fever during the summer just past. Thousands had been. Hundreds had died. Many of the survivors were still as appallingly weak as she was.

The woman in Master Eworth’s portrait no longer existed. Perhaps she never had. That painting, hanging beside the companion piece of her husband, John Harington, in the great hall of their country house in Somersetshire, showed a tall, slender woman of twenty-seven with red-gold hair and sparkling dark brown eyes. In Eworth’s rendition, Audrey wore a richly embroidered gown, radiated raw good health, and looked out on the world with confidence.

To the casual observer, aside from the fact that she now wore plain dark red wool for warmth, she might appear unchanged. But Master Eworth knew better. So did Audrey herself. Her vitality had been sapped by recent illness, and she felt at times no more than a wraith.

In spite of the effort it took to cross the room to her daughter’s side, Audrey did not falter, nor did she do more than wince when she reached her goal and knelt beside Hester’s chair. Illusion was more important than reality, a lesson she’d learned well during the years she’d spent on the fringes of the royal court.

Hester stared down at her mother with a sad expression that made her appear far older than her years.

“What is it that troubles you, sweeting?” Audrey asked.

“Nothing.” Hester looked away, toying with the fringe on the arm of the chair.

“Is your hair braided too tightly?” The thick, dark brown tresses, an inheritance from her father, had been pulled back from her face and wound in an intricate manner on top of her head.

“No, Mother.”

“Then you must keep your promise to pose for Master Eworth. When your portrait is finished, it will hang in the great hall at Catherine’s Court.”

“Distract her, madam,” Eworth interrupted, anxious to resume work. “She must remain motionless if I am to do her justice.”

“How long?” Audrey did not look at him.

“Another hour at the least.”

At this pronouncement, Hester’s lower lip crept forward in a pout.

“Pick up the book and pretend to read,” Eworth ordered. “For some unfathomable reason Master Harington wants the world to know he has a well-educated daughter.”

“What if I read to you?” Audrey cut in before the rebellion she saw bubbling up in the dark eyes so like her own could boil over. “Then all you will have to do is sit still and listen.”

Hester made a circle on the floor with the toe of her little leather slipper. “What will you read?”

“You may choose any text you like, so long as the book is written in English.” The Haringtons owned a respectable library, but some of the volumes were in Latin or Greek or French and beyond Audrey’s ken.

“Tell me a story instead. Tell me a true story about King Henry.”

Audrey sighed. She should have anticipated her daughter’s request. Of late there had been no curtailing Hester’s curiosity about the late king. His portrait—a copy of one Master Holbein had painted—had always been displayed at Catherine’s Court, but Hester had shown no interest in it until, one bleak and stormy winter evening, her father had entertained her by recollecting the days long ago when he had been a gentleman of the king’s Chapel Royal.

Since then, Hester frequently asked for more tales of that time. Her father had recounted a few of his adventures, carefully edited, but Audrey had been reluctant to speak of the past.

Then she had fallen ill. Coming within a hair’s breadth of death had brought home to her that she had a duty to tell Hester the truth—all of it. But the girl was still so young. Could she even comprehend what Audrey had experienced? She wished she could wait until her daughter was a few years older, but she feared to delay too long lest the opportunity be lost forever.

Master Eworth scuttled forward to reposition his subject with the book. Audrey waited until he returned to his easel before she began to speak. She kept her voice low, although she was certain the portrait painter’s hearing was sharp enough to overhear every word she spoke.

It did not matter. In the short time allotted to the sitting, she could not delve very deeply into her story. To tell the complete tale would take many hours, perhaps even days. A sense of calm came over her as she began to speak.

“The first time I met King Henry,” she told her daughter, “I was younger than you are now.”

2

Windsor Castle, 1532

Even as a little girl, I remembered my mother complained often of the cold and bitter winter that preceded my birth. Even the sea froze. And then, while she was still great with child, a plague came upon the land. It was called the sweat, the same vile illness that returned twenty years later to decimate the population of our fair isle. Thousands sickened and died, rich and poor alike. A few sickened and lived. My mother, Joanna Dingley by name, escaped unaffected. On the twenty-third of June, St. Ethelreda’s Day, in the twentieth year of the reign of King Henry the Eighth, she gave birth to me in a house near Windsor Castle. She named me for the saint whose day it was, the patroness of widows and those with ailments of the neck and throat.

Like most girls christened Ethelreda, I have always been called by the diminutive Audrey.

I remember little of the first few years of my life. My mother worked as a laundress at the castle. She smelled of lye and black soap and the warm urine used for bleaching. She had long, black hair and eyes of a brown so dark that it was difficult to discern her pupils. Her face was long and narrow, her coloring sallow. Her hands were strong. When she hit me, it hurt.

After she married a man called Dobson, we moved into his tiny lodgings inside Windsor Castle. He worked in the kitchen as an undercook and slept above it, which meant that the good smells of baking were as often present in our single small chamber as the less pleasant scents of the laundry. Since Dobson had little patience with me, I tried to stay out of his way. His blows were much harder than those my mother gave me. When he hit me, he always left bruises.

Dobson was in a particularly foul mood on the September Sunday in the year of our Lord fifteen hundred and thirty-two when Lady Anne Rochford, she who would one day become Queen Anne Boleyn, was to be created Marquess of Pembroke. He had to rise very early—well before dawn—to prepare food for a banquet. When he got up, he tripped over the truckle bed where I lay sleeping. I was a little more than four years old and still half asleep, incapable of moving fast enough to escape. Cursing loudly, he kicked me twice, once in the ribs and once in the face.

You may well ask how I can recall anything from so early in my childhood, let alone in such detail. In truth, I cannot explain it. Most of what befell me between my birth and the age of eight or nine beyond my mother’s complaints I retain only in vague impressions. And yet, there are one or two incidents that must have imprinted themselves too vividly upon my mind ever to be forgotten. This was one such, and it changed my life.

My memory of Dobson’s kicks is as fresh as if they connected with my flesh only yesterday. I can still recall how the pain brought tears to my eyes and that I did not dare cry out. If I’d made a sound, it would only have made him angrier. Instead, while he stumbled about, lighting a candle, using the chamber pot behind the screen, and pulling on his clothing, I crept out of our lodgings. Heedless of direction, still barefoot and clad in nothing more than my white linen shift, I ignored the throbbing in my ribs and ran for all I was worth.

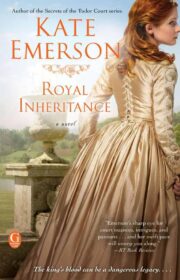

"Royal Inheritance" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Royal Inheritance". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Royal Inheritance" друзьям в соцсетях.