top articles in the paper. Last week Janey had written about her marriage, giving rather too many intimate details. Most people, including Billy, thought it was very funny. Mrs. Lloyd-Foxe did not.

“How’s dear Helen and darling little Marcus?” she asked, every time she rang Janey, knowing it would irritate her.

Mrs. Lloyd-Foxe had daughters, who seemed to lay babies with the ease that chickens produce eggs. It was up to Janey, her mother-in-law implied frequently, to produce a son as soon as possible. “Then there’ll be a little Lloyd-Foxe to carry on the line.”

Helen, feeling slightly sick, but much happier after her rapprochement with Rupert, was thrilled she was having another baby. Janey wanted to be pregnant, too and hadn’t taken the Pill since she’d been married to Billy. But each month it was just the same. She went to see her doctor, who said it was very early days and suggested she had her tubes blown.

“You’ve also been racketing round the world a lot,” he told her. “Why don’t you stop work for a bit, play house, look after Billy and get in a nesting mood? Try to confine intercourse to the middle of the month, between your periods.”

Janey, in fact, was bored with racketing around. She was fed up with living out of suitcases, interviewing pop stars and heads of state. She wanted to stay at home and watch the lime trees round the cottage turn yellow, and go out mushrooming in the early morning.

There was also the matter of her expenses, which were colossal, and which had very few bills to back them up, because Janey had lost them. There had been too many dinners for ten at Tiberio’s or Maxim’s, with Janey and Billy treating the rest of the team. The show-jumping correspondent, jealous of her pitch being queered by Janey, had sneaked to the sports editor about unnecessary extravagance. The editor, Mike Pardoe, nearly had a coronary when he saw the total and summoned Janey from Gloucestershire.

Pardoe had once been Janey’s lover. As she looked at his handsome watchful, wolfish face, Janey thought how much much nicer Billy was.

“These expenses are a joke,” said Pardoe. “How the hell did you spend so much money in Athens? Did you buy one of the Greek islands?”

“Well, the copy was good. You said so.”

“It’s gone off recently. Most of it seems to have been written with your pen dipped in Mouton Cadet and from a hotel bedroom. I want you to come back to Fleet Street where I can keep an eye on you and put you on features I need. You’re a good writer, Janey, but you’ve lost your edge.”

“I want to write a diary from the country, rather like The Diary of a Provincial Lady,” protested Janey.

“Who the hell’s interested in that?”

Janey was livid. She looked at Pardoe’s fridge, laden with drink, and the leather sofa, on which he’d laid her many years before, and which had just been upholstered in shiny black. She didn’t want to go back to that wild, uncertain pre-Billy existence, where you shivered on the tube platform on the way to work, in the dress you’d worn the night before and everyone knew you hadn’t been home.

She went off and lunched with a publishing friend and told him she wanted to write a book on men and where they stood at this moment in the sexual war. “I’m going to call it Dispatches from the Y-Front.”

“Good idea,” said the publishing friend. “Make a nice change from all this feminist rubbish pouring off the presses. Take in the lot: divorcées, adulterers, house husbands. Is the post-permissive male better in bed? Make it as bitchy, funny, and as contentious as possible. I’ll give you a £21,000 advance.”

Tight after lunch, Janey went back to Pardoe and handed in her notice.

“You’ll be back,” he said. “If you ever finish that book, which I very much doubt, I might serialize it.”

“I doubt it,” said Janey, “because you’ll certainly be in it, and you’ll be too vain to sue.”

Janey was not that worried about how long she’d take over the book. Her father had supported her mother. Why shouldn’t Billy support her? Billy came back from Hamburg to be told Janey had resigned, but was being paid a big advance to write a book.

“I’m going to be a proper wife, like Helen,” she went on.

Billy said he preferred improper wives and, although he liked the idea of her living in the woodcutter’s cottage, like Little Red Riding Hood, he did hope too many wolves wouldn’t turn up dressed as grandmothers. He was also slightly alarmed that, along with the £50,000 bill from the builders, there was a tax bill for £10,000 and Janey’s VAT for £3,000. Suddenly there didn’t seem to be anything to pay them with.

“Give the bills to Kev,” said Janey, airily. “That’s what he’s there for.”

But all worries about money were set aside with the excitement of moving in and the furniture looking so nice on the stone floors and lighting huge log fires in the drawing room and cutting back the roses and honeysuckle which were still in flower and darkening the windows. Then there was the bliss of waking up in their own bed in their own room, looking through the lime trees at the valley. How could they not be happy and prosper in an enchanted bower like this?

Janey missed Billy when he started going off to shows without her, but she was enjoying getting things straight, and it was heaven not having to get up at five o’clock in the morning to drive off over mountain passes or break down on icy roads. The winter that followed was very cold, and the wind whistled past their door straight off the Bristol Channel, but Janey merely turned the central heating up to tropical and thought idly about her book. The muse must not be raped; she must be given time to yield her secrets.

Rupert missed them both terribly when they moved out. All the fun seemed to have gone out of the house. He was making heroic attempts to be a good husband and Helen was trying equally hard to be more sexy. But when you were feeling sick and heavy with pregnancy, it wasn’t easy. Badger missed Mavis most of all, and spent days down at the cottage whenever Rupert was away. When Rupert arrived to fetch him, he would lie in front of the fire in embarrassment with his eyes shut, pretending that, because he couldn’t see Rupert, he wasn’t there.

As an ingratiating gesture, Janey invited Kev and Enid Coley to her first dinner party. The huge china poodle was unearthed from its home in the cellar, dusted down, and put in its place of honor in the drawing room. Unfortunately, Janey had sprayed oven cleaner all over the inside of the cooker the day before and had forgotten to wash it off, so when she removed the duck from the oven, the kitchen was flooded with toxic fumes and the duck was a charred wreck, the size of a wren. So everyone screamed with laughter and Billy was sent off to Stroud to get a Chinese takeout. Just as well, perhaps. When Billy checked the mustard Janey’d put on the table, he discovered it was the horses’ saffron anti-fly ointment.

“Janey’s very attractive,” commented Enid Coley on the way home, “but I’m not sure she’s a homemaker.”

By the time Christmas came, things were very tight. The Bull bruised a sole before the Olympia show and Billy didn’t have a single win with the other horses. He sent a Christmas card to his bank manager and decided he’d have to tap his parents, who’d invited them down for Christmas.

“Only for a couple of days,” Janey told Mrs. Lloyd-Foxe, firmly. “We can’t really leave the horses.”

The visit was not a success. Janey, who always left shopping until the last moment, was forced to spend an absolute fortune on Christmas presents, which shocked Billy’s frugal parents, who gave them a hideously ugly piece of family silver, instead of the check they had anticipated.

The Lloyd-Foxes lived in a house called The Maltings, which was so cold that Janey couldn’t bring herself to get up until lunchtime, and then only to hog the fire. Billy’s mother was not tactful. She came back incessantly to the subject of babies. It was so sad at bridge parties not to be able to boast of a little Lloyd-Foxe baby in the offing. She was so pleased dear Helen was being sensible and having a second child.

“I’ll iron Billy’s shirts for him,” she said, coming into the bedroom and picking them off the floor. “I know how he likes them, and I’ll make you an apple pie to take back to Gloucestershire. He so loves puddings.”

“She’ll get it in her kisser if she doesn’t shut up,” muttered Janey.

Out of sheer irritation, Janey left her room like a tip, with the fire on, and didn’t bother to make the one bed they’d slept in, out of the two single beds. Billy was the only form of central heating in the house. And as, at noon and six o’clock, Janey moved towards the vodka, Billy’s mother’s jaw quilted with muscles. She was very tired with cooking and she could have done with a little help and praise from Janey. Finally, on Boxing night, Billy asked his father for a loan.

Mr. Lloyd-Foxe hummed and hawed and said it had been a bad year with the squeeze and, although he had twenty thousand to spare, he had divided it between Billy’s sisters, Arabella and Lucinda.

“I feel they need it more than you and Janey do, as you’re both working.”

Janey didn’t even bother to kiss her mother-in-law good-bye, and it was only after they’d left that Mrs. Lloyd-Foxe discovered Janey had painted the letter “L” out of the The Maltings sign on the gate.

After Christmas the bills came flooding in. Billy, who’d never paid a gas or telephone or electricity bill in his life, had no idea they’d be so high. He also read his bank statement, which was infinitely more scarlet after Janey’s Christmas shopping spree.

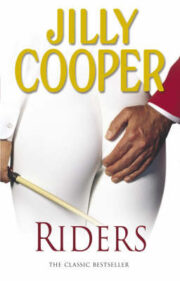

"Riders" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Riders". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Riders" друзьям в соцсетях.