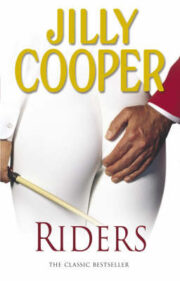

Jilly Cooper

Riders

To Beryl Hill,

the Artur Rubinstein of the typewriter,

with love and gratitude

Acknowledgments

An enormous number of people helped me write Riders. They were all experts in their fields. But this being a work of fiction, I took their advice only as far as it suited my plot, and the accuracy of the book in no way reflected on their expertise!

They included Ronnie Massarella, Caroline Silver, Alan Smith, Brian Giles, Douglas Bunn, Michael Clayton, Alan Oliver, Bridget Le Good, John Burbidge, Diana Downie, Raymond Brooks-Ward, Harvey Smith, Dr. Hubert and Mrs. Bessie Crouch, Dr. Timothy Evans, Heather Ross, Caroline Akrill, Dick Stilwell, Sue Clarke, Sue Gibson, Andrew Parker-Bowles, John and Tory Oaksey, Marion Ivey, Rosemary Nunelly, Elizabeth Richardson, Elizabeth Hopkins, Julia Longland, Susan Blair, Ann Martin, Kate O’Sullivan, Marcy Drummond, John and Michael Whitaker, David Broome, and Malcolm Pyrah.

I owed a special debt of gratitude to dear Sighle Gogan, who spent so many hours talking to me about show jumping, and arranged for me to meet so many of the people who helped me, but who tragically died in January 1984.

I also had cause to thank my bank manager, James Atkinson, for being so patient and Paul Scherer and Alan Earney of Corgi Books for being so continually encouraging, and Tom Hartman for being one of those rare people who actually makes authors enjoy having their books edited.

An award for gallantry weny to the nine ladies who all worked fantastically long hours over Christmas, deciphering my appalling handwriting and typing the 340,000-word manuscript. They included Beryl Hill, Anna Gibbs-Kennet, Sue Moore, Margaret McKellican, Corinne Monhaghan, Julie Payne, Nicky Greenshield, Patricia Quatermass, and my own wonderful secretary, Diane Peter.

The lion’s share of my gratitude went to Desmond Elliott for masterminding the whole operation so engagingly, and to all his staff at Arlington, who worked so hard to produce such a huge book in under five months.

Finally there were really no words adequate to thank my husband, Leo, and my children, Felix and Emily, except to say that without their support, good cheer, and continued unselfishness the book would never have been finished.

— England, 2007

1

Because he had to get up unusually early on Saturday, Jake Lovell kept waking up throughout the night, racked by terrifying dreams about being late. In the first dream he couldn’t find his breeches when the collecting ring steward called his number; in the second he couldn’t catch any of the riding school ponies to take them to the show; in the third Africa slipped her head collar and escaped; and in the fourth, the most terrifying of all, he was back in the children’s home screaming and clawing at locked iron gates, while Rupert Campbell-Black rode Africa off down the High Street, until turning with that hateful, sneering smile, he’d shouted: “You’ll never get out of that place now, Gyppo; it’s where you belong.”

Jake woke sobbing, heart bursting, drenched in sweat, paralyzed with fear. It was half a minute before he could reach out and switch on the bedside lamp. He lit a cigarette with a trembling hand. Gradually the familiar objects in the room reasserted themselves: the Lionel Edwards prints on the walls, the tattered piles of Horse and Hound, the books on show jumping hopelessly overcrowding the bookshelves, the wash basin, the faded photographs of his mother and father. Hanging in the wardrobe was the check riding coat Mrs. Wilton had rather grudgingly given him for his twenty-first birthday. Beneath it stood the scratched but gleaming pair of brown-topped boots he’d picked up secondhand last week.

In the stall below he could hear a horse snorting and a crash as another horse kicked over its water bucket.

Far too slowly his panic subsided. Prep school and Rupert Campbell-Black were things of the past. It was 1970 and he had been out of the children’s home for four years now. He mostly forgot them during the day; it was only in dreams they came back to torment him. He shivered; the sheets were still damp with sweat. Four-thirty, said his alarm clock; there were already fingers of light under the thin yellow curtains. He didn’t have to get up for half an hour, but he was too scared to go back to sleep. He could hear the rain pattering on the roof outside and dripping from the gutter, muting the chatter of the sparrows.

He tried to concentrate on the day ahead, which didn’t make him feel much more cheerful. One of the worst things about working in a riding school was having to take pupils to horse shows. Few of them could control the bored, broken-down ponies. Many were spoilt; others, terrified, were only riding at all because their frightful mothers were using horses to grapple their way up the social scale, giving them an excuse to put a hard hat in the back window of the Jaguar and slap gymkhana stickers on the windscreen.

What made Jake sick with nerves, however, was that, unknown to his boss, Mrs. Wilton, he intended to take Africa to the show and enter her for the open jumping. Mrs. Wilton didn’t allow Jake to compete in shows. He might get too big for his boots. His job was to act as constant nursemaid to the pupils, not to jump valuable horses behind her back.

Usually, Mrs. Wilton turned up at shows in the afternoon and strutted about chatting up the mothers. But today, because she was driving down to Brighton to chat up some rich uncle who had no children, she wouldn’t be putting in an appearance. If Jake didn’t try out Africa today, he wouldn’t have another chance for weeks.

Africa was a livery horse, looked after at the riding school, but owned by an actor named Bobby Cotterel, who’d bought her in a fit of enthusiasm after starring in Dick Turpin. A few weeks later he had bought a Ferrari and, apart from still paying her livery fees, had forgotten about Africa, which had given Jake the perfect opportunity to teach her to jump on the quiet.

She was only six, but every day Jake became more convinced that she had the makings of a great show jumper. It was not just her larkiness and courage, her fantastic turn of speed and huge jump. She also had an ability to get herself out of trouble which counterbalanced her impetuosity.

Jake adored her — more than any person or animal he had known in his life. If Mrs. Wilton discovered he’d taken her to a show, she’d probably sack him. He dreaded losing a job which had brought him his first security in years, but the prospect of losing Africa was infinitely worse.

The alarm made him jump. It was still raining; the horror of the dream gripped him again. What would happen if Africa slipped when she was taking off or landing? He dressed and, lifting up the trapdoor at the bottom of his bed, climbed down the stairs into the tackroom, inhaling the smell of warm horse leather, saddle soap, and dung, which never failed to excite him. Hearing him mixing the feeds, horses’ heads came out over the half-doors, calling, whickering, stamping their hooves.

Dandelion, the skewbald, the greediest pony in the yard, his mane and back covered in straw from lying down, yelled shrilly, demanding to be fed first. As he added extra vitamins, nuts, and oats to Africa’s bowl, Jake thought it was hardly surprising she looked well. Mrs. Wilton would have a fit if she knew.

It was seven-thirty before he had mucked out and fed all the horses. Africa, feed finished, blinking her big, dark blue eyes in the low-angled sun, hung out of her box, catching his sleeve between her lips each time he went past, shaking gently, never nipping the skin. Mrs. Wilton had been out to dinner the night before; it was unlikely she’d surface before half-past eight; that gave him an hour to groom Africa.

Rolling up his sleeves, chattering nonsense to her all the time, Jake got to work. She was a beautiful horse, very dark brown, her coat looking almost indigo in the shadows. She had two white socks, a spillikin of white down her forehead, a chest like a channel steamer funnel, huge shoulders and quarters above lean strong legs. Her ears twitched and turned all the time, as sensitive as radar.

He started when the stable cat, a fat tabby with huge whiskers, appeared on top of the stable door and, after glancing at a couple of pigeons scratching for corn, dropped down into the straw and curled up in the discarded warmth of Africa’s rug.

Suddenly Africa jerked up her head and listened. Jake stepped outside nervously; the curtains were still drawn in Mrs. Wilton’s house. He’d wanted to plait Africa’s mane, but he didn’t dare. It would unplait all curly and he might be caught out. He went back to work.

“Surely you’re not taking Africa to the show?” said a shrill voice. Jake jumped out of his skin and Africa tossed up her head, banging him on the nose.

Just able to look over the half-door was one of his pupils, Fenella Maxwell, her face as freckled as a robin’s egg, her flaxen hair already escaping from its elastic bands.

“What the hell are you doing here?” said Jake furiously, his eyes watering. “I said no one was allowed here till ten and it can’t be eight yet. Push off home.”

“I’ve come to help,” said Fenella, gazing at him with huge, Cambridge-blue eyes fringed with thick blond lashes. Totally unabashed, she moved a boiled sweet to the other side of her face.

“I know you’re by yourself till Alison comes. I’ll get Dandelion ready…please,” she added. “I want him to look as beautiful as Africa.”

"Riders" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Riders". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Riders" друзьям в соцсетях.