A girl on a heavily bandaged dappled gray came in and jumped a brisk clear round.

Next came Sally Ann Thomson.

“Here’s my little girl,” said Mrs. Thomson, pausing for a moment in her discussion of hats with Mrs. Maxwell. “I wonder if Stardust will go better in a running martingale.”

Stardust decided not and refused three times at the first fence.

“We really ought to buy her a pony of her own,” said Mrs. Thomson. “Even the best riders can’t do much on riding-school hacks.”

Mrs. Maxwell winked at Colonel Carter.

Round followed round; everyone agreed the standard was frightful.

“And here we have yet another competitor from Brook Farm Riding School: Miss Patty Beasley on Swindle.”

Swindle trotted dejectedly into the ring, rolling-eyed and thin-legged, like a horse in a medieval tapestry. Then, like a car running out of petrol, she ground to a halt in front of the first fence.

Jake raised his eyes to heaven.

“Jesus Christ,” he muttered.

Swindle’s third refusal was too much for Patty’s father, who’d bought breeches specially to attend the show. Rushing across the grass he brandished a shooting stick shouting, “Geron.” Terrified, Swindle rose like a stag from the hard ground and took a great leap over the brush fence, whereupon Patty fell off and burst into tears.

“Another competitor from Brook Farm Riding School eliminated,” said Dudley Diplock.

“Teach them to fall off there, don’t they?” said a wag.

The crowd guffawed. Jake gritted his teeth. He was aware of Tory standing beside him and, sensing her sympathy, was grateful.

“It’s your turn next,” said Jake, going up to Fen and checking Dandelion’s girths. “Take the double slowly. Everyone else has come round the corner too fast and not given themselves enough time. Off you go,” he added, gently pulling Dandelion’s ears.

“Please, God, I’ll never be bad again,” prayed Fen. “I won’t be foul to Sally Ann or call Patty a drip, or be rude to Mummy. Just let me get round.”

Ignoring the cries of good luck, desperately trying to remember everything Jake had told her, Fen rode into the ring with a set expression on her face.

“Miss Fenella Maxwell, from Brook Farm Riding School,” said the radio personality. “Let’s have a round of applause for our youngest competitor.”

The crowd, scenting carnage, clapped lethargically. Dandelion, his brown and white patches gleaming like a conker that had been opened too early, gave a good-natured buck.

“Isn’t that your little girl?” said Mrs. Thomson.

“So it is,” said Molly Maxwell, “Oh look, her pony’s going to the lav. Don’t horses have an awful sense of timing?”

The first fence loomed as high as Becher’s Brook and Fen used her legs so fiercely, Dandelion rose into the air, clearing it by a foot.

Fen was slightly unseated and unable to get straight in the saddle to ride Dandelion properly at the gate. He slowed down and refused; when Fen whacked him he rolled his eyes, swished his tail, and started to graze. The crowd laughed; Fen went crimson.

“Oh, poor thing,” murmured Tory in anguish.

Fen pulled his head up and let him examine the gate. Dandelion sniffed, decided it was harmless and, with a whisk of his fat rump, flew over and went bucketing on to clear the stile, at which Fen lost her stirrup, then cleared the parallel bars, where she lost the other stirrup. Rounding the corner for home, Dandelion stepped up the pace. Fen checked him, her hat falling over her nose, as he bounded towards the road-closed sign. Dandelion, fighting for his head, rapped the fence, but it stayed put.

I can’t bear to look, thought Tory, shutting her eyes.

Fen had lost her hat now and, plaits flying, raced towards the triple. Jake watched her strain every nerve to get the takeoff right. Dandelion cleared it by inches and galloped out of the ring to loud applause.

“Miss Fenella Maxwell on Dandelion, only three faults for a refusal; jolly good round,” coughed the microphone.

“I had no idea she’d improved so much,” said Tory, turning a pink, ecstatic face towards Jake.

Fen cantered up, grinning from ear to ear.

“Wasn’t Dandelion wonderful?” she said, jumping off, flinging her arms round his neck, covering him with kisses, and stuffing him with sugar lumps.

She looked up at Jake inquiringly: “Well?”

“We could see half the show ground between your knees and the saddle, and you took him too fast at the gate, but not bad,” he said.

For the first time that day he looked cheerful, and Tory thought how nice he was.

“I must go and congratulate Fen,” said Mrs. Maxwell, delicately picking her way through the dung that Manners had not yet gathered.

“Well done, darling,” she shrieked in a loud voice, which made all the nearby horses jump. “What a good boy,” she added, gingerly patting Dandelion’s nose with a gloved hand. “He is a boy, isn’t he?” She tilted her head sideways to look.

“Awfully good show,” said Colonel Carter. “My sister used to jump on horseback in Hampshar.”

Mrs. Maxwell turned to Jake, enveloping him in a sickening waft of Arpège.

“Fen really has come on. I do hope she isn’t too much of a nuisance down at the stables all day, but she is utterly pony-mad. Every sentence begins, ‘Jake said this, Jake says that’; you’ve become quite an ogre in our home.”

“Oh, Mummy,” groaned Fen.

Jake, thinking how silly she was and unable to think of anything to say in reply, remained silent.

How gauche he is, thought Molly Maxwell.

The junior class, having finished jumping off, were riding into the ring to collect their rosettes.

“Number Eighty-six,” howled the collecting ring steward. “Number Eighty-six.”

“That’s you, Fen,” said Tory in excitement.

“It couldn’t be. I had a refusal.”

“You’re fourth,” said Jake, “go on.”

“I couldn’t be.”

“Number Eighty-six, for the last time,” bellowed the ring steward.

“It is me,” said Fen, and scrambling onto Dandelion, plonking her hat on her head, and not wearing a riding coat, she cantered into the ring, where she thanked Miss Bilborough three times for her rosette. Success went to Dandelion’s head and his feet. Thinking the lap of honor was a race, he barged ahead of the other three winners, carting Fen out of the ring and galloping half round the show ground before she could pull him to a halt in front of Jake. He shook his head disapprovingly.

Fen giggled. “Wouldn’t it be lovely if Africa got one too?”

3

The afternoon wore on, getting hotter. The Lady Mayoress, sweating in her scarlet robes, had a bright yellow nose from sniffing Lady Dorothy’s lilies. The band was playing “Land of Hope and Glory” in the main ring as the fences for the open jumping were put up, the sun glinting on their brass instruments. Mrs. Thomson and Mrs. Maxwell moved their deck chairs to the right, following the sun, and agreed that Jake was extremely rude.

“I’m going to have a word with Joyce Wilton about it,” said Molly Maxwell.

“Horse, horse, horse,” said Mr. Thomson.

“I can never get Fen to wear a dress; she’s never been interested in dolls,” said Molly Maxwell, who was still crowing over Fen’s rosette.

“I’m pleased Sally Ann has not lost her femininity,” said Mrs. Thomson.

“It’s extraordinary how many people read The Tatler,” said Mrs. Maxwell.

“Mrs. Squires to the judges’ tent,” announced the address system.

“Miss Squires, Miss Squires,” snapped the hairnetted lady judge, stumping across the ring.

“Wasn’t Dandelion wonderful?” said Fen for the hundreth time.

Tory could feel the sweat dripping between her breasts and down her ribs. She’d taken off her red jacket and hung her white shirt outside, over the straining safety pin.

Competitors in the open jumping were pulling on long black boots, the women tucking long hair into hairnets and hotting up their horses over the practice fence. With £100 first prize there was a lot of competition from neighboring counties. Two well-known show jumpers, Lavinia Greenslade and Christopher Crossley, who’d both jumped at Wembley and for the British junior team, had entered, but local hopes were pinned on Sir William’s son, Michael, who was riding a gray six-year-old called Prescott.

Armored cars and tanks had started driving up the hill for the dry shoot and the recruiting display. Soldiers, sweating in battle dress, were assembling twenty-five pounders in ring two.

“Christ, here comes Carter’s circus,” said Malise Gordon to Miss Squires.

“Hope he can keep them under control.”

“My chaps have arrived,” said Colonel Carter to Mrs. Maxwell. “I’m just going to wander over and see that everything’s all right.”

Jake gave Africa a last polish. Tory, noticing his dead white face, shaking hands, and chattering teeth, realized how terrified he was and felt sorry for him. He put a foot in the stirrup and was up.

If only I weren’t so frightened of horses I might not be frightened of life, thought Tory, cringing against the rope to avoid these great snorting beasts with their huge iron feet and so much power in their gleaming, barging quarters.

The band went out to much applause and, to everyone’s dismay, came back again. Jake rode up to Tory and jumped off.

“Can you hold her for a minute?” he said, hurling the reins at her.

He only just made the Gents’ in time.

Looking into the deep, dark dell of the Elsan, and catching a whiff of the contents, he was violently sick again. He must pull himself together or Africa would sense his nerves. Mrs. Wilton wouldn’t find out; the kids could cope in the gymkhana events for half an hour by themselves. He’d be all right once he got into the ring. He’d walked the course; there was nothing Africa couldn’t jump if he put her right. He leant against the canvas and wondered if he dared risk another cigarette.

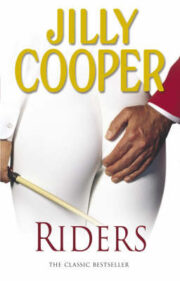

"Riders" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Riders". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Riders" друзьям в соцсетях.