She remembered the day Rupert had asked her to marry him. In the afternoon she’d been sitting in the stands with Doreen, Humpty Hamilton’s even fatter, bouncier wife, mother of two children, watching Rupert and Humpty jump in a class. Helen, delirious with happiness, couldn’t resist telling Doreen she was engaged. Doreen Hamilton was delighted at the news and promptly bore Helen off to the bar for a celebration drink, then offered her a word of advice.

“If you marry a show jumper,” she said, “involve yourself in his career as much as possible and travel with him as much as you can, even if it means sleeping in lorries, or caravans, or frightful pokey foreign hotels. And if he suddenly rings up when you’re at home and says come out to Rome, or drive down to Windsor, or to Crittleden, always go — at once, even if you’ve just washed your hair and put it in curlers, or you’ve just got the baby to sleep. Because if you don’t, there’ll always be others queuing up to take your place.”

Helen, cocooned in the miracle of her new and reciprocated love for Rupert, was unable to imagine him loving anyone else, or any girl queuing up for fat little Humpty, but she had heeded the advice and gone with Rupert to as many shows as possible. Not that this involved much hardship; his caravan was extremely luxurious and when they went abroad Rupert insisted on staying in decent hotels or with rich jet-set friends who seemed to surface, crying welcome, in every country they visited. But it meant she always had to look her best.

Going to the window, with its rampaging frame of scented palest pink clematis, she gazed out across the valley, emerald green from weeks of heavy rain, remembering the first time she’d seen the house. Rupert and Billy, having both won big classes on the final day of the Royal Plymouth, decided to stay on for the closing party that night. After intensive revelry, Rupert suddenly turned to Helen and said, “I think it’s time you had a look at my bachelor pad,” and they loaded up the horse box and set out for Gloucestershire, Rupert driving, Helen sitting warm between the two men. “An exquisite sliver of smoked salmon between two very old stale pieces of bread,” said Billy.

Helen went to sleep and woke up as they drove up the valley towards Penscombe. The sun had just risen, firing a denim blue sky with ripples of crimson and reddening the ramparts of cow parsley on either side of the road. Suddenly the horses started pawing the floorboards in the back and Mavis and Badger, who were sprawled across Billy’s and Helen’s knees in the front, woke up and started sniffing excitedly.

“Ouch,” said Billy as Badger stepped heavily across him. “Get off my crotch. Why the hell don’t you get his claws cut, Rupe?”

Helen looked across the valley at the honey gold house leaning back against its pale green pillow of beech trees.

“What a beautiful mansion,” she gasped. “I wonder who lives there?”

“You do,” said Rupert. “That’s your new home,” and he and Billy laughed to see how speechless she was.

“I can’t believe it,” she whispered. “It’s so old and so beautiful. It’s a stately home.”

“You may not find it quite so splendid when you get close to,” said Rupert, slowing down as they entered the village.

He took the lorry straight round to the stables, where Marion and Tracey, who’d driven home the night before with the caravan, were waiting to unload the horses. Leaving Billy to check everything was all right, Rupert whipped into the house, collected a bottle of champagne and two glasses, and took Helen out on the terrace.

Below them lay the valley, drenched white with dew, softened by the palest gray mist rising from the stream that ran along the bottom. On the opposite hillside, the sun was filtering thick biblical rays through the trees, which in turn cast long powder blue shadows down the fields. And, sauntering leisurely down one of these rays like horses of the dawn, came three of Rupert’s sleek and beautiful thoroughbreds, two grays and a chestnut. Tossing their heads, they broke into a gallop and careered joyously down the white valley, vanishing into the mist like a dream.

Leaning on the stone balustrade on the edge of the terrace, Helen gazed and gazed. Behind her the wood was filled with bluebells; thrushes were singing out of a clump of white lilacs to the left. Badger, after the long journey, wandered around lifting his leg on bright yellow irises, before happily plunging into the lake.

“It’s the most beautiful place I’ve ever seen,” she breathed. “You’re not a closet earl or anything, are you? I feel like King Cophetua and the Beggar Maid.”

“King who?” asked Rupert, hitching a hip onto the lichened balustrade and edging open the champagne with his thumbs. The cork flew through the air, landing in a rosebush.

“Is it all yours?”

“As far as that village on the right.” He filled a glass and handed it to her.

“Anyway it’s yours too now, darling, every inch of it.”

Looking up, she saw he was smiling. Even an eighth of an inch of blond stubble, and a slight puffiness round the wickedly sparkling eyes, couldn’t diminish his beauty.

“Just as every single inch of you belongs to me from now on,” he added softly.

Then she realized it was not King Cophetua he reminded her of, but the Devil tempting Christ in the wilderness, saying, “All this will I give you.”

Just for a second she had a premonition of unease. Then Rupert chinked his glass against hers and, draining it, said, “Let’s go to bed.”

“We can’t,” stammered Helen. “What will everyone think?”

“That we’ve gone to bed,” said Rupert.

Upstairs he pulled the telephone out, but didn’t bother to lock the door.

“Well, at least I’m going to draw the curtains,” said Helen.

“I wouldn’t,” said Rupert.

But the next minute she’d given the dark red velvet a vigorous tug and the whole thing descended, curtain rail and all, on her head in a huge cloud of dust. In fits of laughter, Rupert extracted her.

“I told you not to pull it!” Then, seeing her hair covered in dust, “My God you’ve gone white overnight. Must be the effect of saying you’ll marry me.”

He pulled her into the shade of the great ancient four-poster and began unbuttoning her shirt. Next minute she leapt out of her skin as the door opened. But it was only Badger, dripping from the lake, trying to join them in bed.

“Basket,” snapped Rupert. “And you might bloody well shut the door,” he added, kicking it shut.

After Rupert had come, with that splendid driving flourish of staccato thrusts which reminded Helen of the end of a Beethoven symphony, he fell into a deep sleep. Helen, lying in his arms, had been far too tense and nervous of interruption to gain any satisfaction. Looking around the room, she took in the mothy fox masks leering down from the walls, the Munnings and the Lionel Edwards, and surely that was a Stubbs in the corner, very much in need of a clean. All the furniture in the room was old and handsome, but it too was desperately in need of a polish, and all the chairs and the sofa needed reupholstering. There were angora rabbits of dust on top of every picture, and sailors could have climbed up the rigging of cobwebs in the corners. Judging by the color of the bed linen, it hadn’t seen a washing machine for weeks. Helen began to itch and edged out of Rupert’s embrace. She was touched to see a copy of War and Peace by the bedside table. At least he was trying to educate himself. Writing “I love you” in the dust, she wandered off to find a bathroom.

She found the john first, and was less touched to find a framed photograph on the wall of Rupert on a horse, being presented with a cup by Grania Pringle. Along the bottom Grania had written, “So happy to mount you — love Grania.” That’s one for the jumble sale, thought Helen, taking it off the wall.

The bathroom made her faint. A great white bath, standing six inches off the ground on legs shaped like lion’s paws, was ringed with grime like a rugger sweater. Above it, a geyser on the wall spat out dust and then boiling water. The ceiling was black with dirt, the paint peeling like the surface of the moon. On another beautiful chest of drawers, which was warping from the damp, stood empty bottles, mugs, and two ashtrays brimming over with cigarette stubs.

Having found a moderately clean towel and spent nearly an hour cleaning the bath, she had one herself, then set out to explore the house, finding bedroom after bedroom filled with wonderful furniture, carpets, and china, with many of the beds recently slept in but not made. At the end of the passage she discovered a room which was obviously Billy’s. On the chest of drawers was a large photograph in a frame of Lavinia Greenslade, and an even larger one of Mavis. There were glasses by the bed and drink rings on everything.

A bridle hung from the four-poster. There were sporting prints on the wall and more framed photographs of horses jumping, galloping, standing still, and being presented with rosettes. On the chest of drawers was a pile of unopened brown envelopes and more overflowing ashtrays.

Descending the splendid staircase with a fat crimson cord attached to the wall to cling on to, she admired a huge painting of Badger in the hall. Underneath it two Jack Russells were having a fight. She found a pair of Springer Spaniels shut in the drawing room. Every beautiful faded chair and sofa seemed to be upholstered in dog hair. On the wall was a large lighter patch where a painting had been sold. The rest of the walls were covered, among other things, by a Romney, a Gainsborough, a Lely, and a Thomas Lawrence. Next door, behind the inevitable wire cages, was the library. No wonder Rupert was indifferent to culture; it was all around him, to be taken for granted. For a minute, looking at more cobwebs and dust, she thought she’d strayed into Miss Haversham’s house.

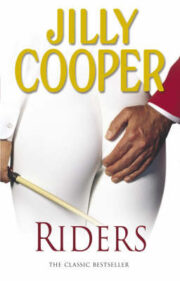

"Riders" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Riders". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Riders" друзьям в соцсетях.