“For a couple of bad rounds in a Nations’ Cup? That’s insane. It wasn’t your fault.”

“Well, it was actually. Malise told us to go to bed early. I never sleep before a Nations’ Cup, so I took Billy out on the tiles. We got more smashed than we meant to. Next day, every double was a quadruple.”

“Oh, Rupert,” wailed Helen, “how could you when you were jumping for Great Britain? Surely you could have gone to bed early one night? And to involve Billy. Malise must have been so disappointed.”

Rupert had expected sympathy, not reproach bordering on disapproval.

“Poor Malise, who’s he going to put in your place?”

“I don’t know, and I don’t want to talk about it.”

Helen could see he was mad, but could not stop herself saying, “I’m just so disappointed. I so wanted to go to Lucerne.”

“We’ll go some other time. Look, I’m off to the Royal Plymouth tomorrow morning. It’s an agricultural and flower show with only a couple of big show-jumping classes a day, so I shan’t be overoccupied. Why don’t you take the rest of the week off and come too?”

Helen was sorely tempted.

“When were you thinking of leaving?”

“Now. I want to avoid the rush hour and I’ve got a lot to catch up on tonight after three weeks away.”

“I can’t.”

“Why not?”

“I’ve got an editorial meeting at three o’clock, and I’ve got to get this manuscript off to the press by Friday. I was planning to have everything clear before Lucerne.”

“And I’ve screwed up your little jaunt. Well, I’m sorry.” He certainly didn’t sound it. Helen warmed to her subject.

“And I do have some sort of responsibility towards my colleagues, unlike you. To go and get drunk before a Nations’ Cup is just infantile. And Malise said you could be the finest rider in Britain if you took it a bit more seriously.”

“Did he indeed?” said Rupert, dangerously quiet. Draining his glass and getting a tenner out of his notecase, he handed it to the barman. “Well, it’s no bloody business of yours or his to discuss me.”

He got to his feet. Helen realized she’d gone too far.

“Malise and I only want what’s best for you,” she stammered.

“Sweet of you both,” said Rupert. “Have a nice meeting. It’s high time you took up with Nige again. You two really suit each other.”

And he was gone.

Rupert returned to Penscombe at eight o’clock the following morning, just as Marion and Tracey were loading up the lorry for the four-hour drive down to Plymouth. He looked terrible and proceeded to complain bitterly about everything in the yard; then went inside to have a bath and emerged twenty minutes later looking very pale but quite under control.

“What’s up with him?” said Tracey.

“Had a tiff with the flame-haired virgin, I should think,” said Marion.

Her suspicions were confirmed when Rupert started to quibble about the order in which the horses were being loaded.

“Who are you putting next to The Bull?”

“Macaulay. I thought it would settle him.”

“Don’t call him that. I’m not having him named after that bitch anymore. He can go back to being Satan. Suits him much better.”

With Billy driving, Rupert slept most of the way down to Plymouth. The showground was half a mile outside the town. It was a glorious day. Dazzling white little clouds scampered as gaily across a butcher blue sky as boats with colored sails danced on the sparkling aquamarine ocean. The horses, clattering down the ramp, sniffed the salty air appreciatively. Once in the caravan which Marion had driven down, Rupert poured himself a large measure of whisky.

“Tears before sunset,” said Marion to Tracey.

On their way to the secretary’s tent to declare, Billy was telling Rupert about Ivor Braine’s latest ineptitude.

“He was popping out to the shops, and I asked him to get me a packet of Rothman’s. I said, ‘If you can’t get Rothman’s, get me anything,’ and he comes back with a bloody pork pie.”

Billy suddenly realized he had lost his audience. Glancing round, he noticed that very still, watchful, predatory expression on Rupert’s face, like a leopard who’s just sighted a plump impala. Following Rupert’s gaze, he saw a suntanned blonde in a pale pink sleeveless dress. Probably in her midthirties, she was laying out green baize on a table.

“Gorgeous,” murmured Rupert.

“Married,” said Billy.

“Good,” said Rupert. “I’m fed up with born-again virgins.”

The blonde looked up. She was really very pretty, Billy decided.

Rupert smiled at her. She smiled back, half-puzzled, assuming, because his face was so familiar, that they’d met before. On the way back from declaring, they found her lugging a huge challenge cup out from the car. Other cups were already lined up on the table.

“Let me,” said Rupert, sprinting forward and seizing the cup.

“Oh,” she jumped, “how very kind. Oh, it’s you.” Suddenly, as she realized who Rupert was, she blushed crimson. “I expect you’ll win it later.”

“Hope so,” said Rupert, setting it on the green baize. Then he looked at the inscription. “This one’s actually for lightweight hunters. I’m certainly a hunter,” he shot her an appraising glance, “when the prey’s attractive enough. But not that lightweight.”

She seemed to think this was very funny. It was nice to have someone who laughed at his jokes.

“Shouldn’t your husband be helping you unload this stuff?” He handed her another cup.

“He’s away in Madrid. Some trouble over an order. He had to fly out this morning.”

Better and better, thought Rupert, running his eye over the outline of her round, tight buttocks, as she peered into the back of the car.

“Blast,” she said. “I picked a big bunch of sweetpeas for the table. I must have left them in the porch.”

“They might have slipped under the front seat,” said Rupert, affording himself another good view.

“No.” She emerged, flushed and ruffled. “Oh, dear, and I was going to tie them up with ribbon, as a bouquet for the mayoress.”

“I’ll drive back and pick them up for you.”

“You can’t. It’s awfully sweet of you, but it’s twenty miles.”

Rupert patted her arm. “Leave it with me. I’ll find you a bouquet.”

He went back to the caravan and had another couple of stiff whiskies and then went on the prowl. He peered into the horticultural tent; it was dark and cool, and smelled like a greenhouse, the huge flower arrangements making a rainbow blaze of color. Up at the far end he could see a group of judges poring over some marrows, handling them like vast Indian clubs.

It didn’t take him long to find what he was looking for: a deeply scented bunch of huge, dark crimson roses, with a red first-prize card, and a championship card beside them. Without anyone noticing, he seized the roses and slid out of the tent. No one was about except a large woman in a porkpie hat giving her two Rotweillers a run.

Back at the caravan he put the roses in a pint mug.

“Where did you get those?” demanded Billy, who was pulling on his breeches.

“Never you mind.”

“Inconstant Spry,” said Billy, as Rupert arranged them, then poured himself another whisky.

“You better lay off that stuff,” warned Billy. “And don’t get carried away. We’ve got a class in three-quarters of an hour.”

“Here you are,” Rupert said to the pretty blonde.

“Oh, they’re lovely,” she said. “Ena Harkness, I think, and they smell out of this world. You didn’t go and buy them?”

Rupert smirked noncommittally.

“You did, and you’ve even beaten the stems so they won’t wilt. I’ve got some ribbon in the glove compartment. I’ll hide them in the shade for the moment. I must repay you. Come and have a drink after you’ve finished your class. My name’s Laura Bridges, by the way.”

Rumor raced round the collecting ring as the riders warmed up their horses.

“I hear Rupert’s been dropped,” Driffield said to Billy with some satisfaction.

“Is it twue Malise caught him in bed with a weporter from The Tatler?” giggled Lavinia. “He is awful.”

“For Christ’s sake, don’t say anything to Rupe,” said Billy. “He’s not in the sunniest of moods.”

“What about that gorgeous redhead?” said Humpty. “I wouldn’t mind having a crack at her myself.”

“Nor would I,” said Driffield, “but I gather she doesn’t put out.”

“Shut up,” said Billy. “Here he comes.”

As Rupert cantered up on Macaulay, scattering onlookers, Humpty said, “That horse is new.”

“Where d’you get him?” sneered Driffield. “At a pig fair?”

Everyone laughed, but the smiles were wiped off their faces halfway through the class when Rupert came in and jumped clear. He had reached that pitch of drunkenness when he rode brilliantly, total lack of inhibition giving an edge to his timing. He also made the discovery that Macaulay loved crowds. Used to the adulation of being a troop horse through the streets of London, he really caught fire and become a different animal once he got into the ring and heard applause.

“If you’re going to be that good, perhaps it’s unfair to call you Satan again,” Rupert said as he rode out, patting the horse delightedly.

Over the crowd he could see that the mayoress had arrived and, surrounded by officials, was progressing towards Laura Bridges’s green baize table, no doubt to receive her bouquet. Vaulting off Macaulay, he handed him to Marion and ran off to have a look.

Mr. Harold Maynard, horticultural king of Plymouth, had won the rose championship at the Royal Show for the past five years. Going into the tent, confident he had swept the board for the sixth year, he was thunderstruck to find his prize exhibit missing. He was about to report the loss to the show secretary and get it paged over the loudspeaker, when he suddenly saw his lovingly tended Ena Harkness roses, now done up with a scarlet bow, being handed over to the mayoress by a curtseying Brownie.

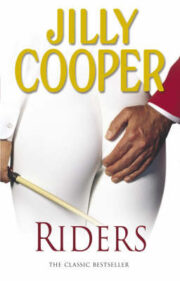

"Riders" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Riders". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Riders" друзьям в соцсетях.