“I am not, I’m wearing a dress.”

“What’s this then?” he pinged the elastic.

“Panties,” said Helen quickly.

Rupert sighed. “There is a language barrier,” he said.

Helen suddenly twigged. “You thought I’d go to a party without panties?” she said in a shocked voice.

“I hoped you might, seeing as how you’re going to take off all your clothes for me later this evening.”

“No,” said Helen, struggling away. “I’m not going to be another of your fancy bits, just to be spat out like chewing gum when the flavor’s gone.”

Rupert started to laugh. “Fancy bit, what an extraordinary phrase. Sounds like a gag snaffle. And I don’t like chewing gum very much. Nanny always said it was common.”

“Why do you trivialize everything?” wailed Helen. “I just don’t want to be rushed.”

“Oh really,” drawled Rupert. “Would you rather we made a date for the year 2000? Would January fifth be okay, or would the sixth suit you better? I’m afraid I can’t make the seventh. Perhaps you could check in your diary.”

“Oh, stop it. I just don’t believe in jumping into bed with people who don’t give a damn for me.”

“You haven’t given me much chance. You can hardly expect me to swear eternal devotion on the second date.”

“I don’t,” sobbed Helen, “I truly don’t. I just don’t want to get hurt again. Harold Mountjoy…”

“Oh dear, now we’re going to be subjected to another sermon on the Mountjoy. Is that it? You only go to bed with married men? If I get married to someone else, then can I fuck you?”

“Please don’t use that kind of language.”

“What’s wrong with the word fuck? That’s what we’re discussing, aren’t we? Stop being so bloody middle class.”

“I am middle class.”

“Personally I think prick-teaser is a much worse word than fuck. Why the hell did you come down here, then?”

“I wanted to see you.”

“You can, all of me. Come back to the caravan.”

“No!” screamed Helen. “I’m going back to London.”

“How?” asked Rupert.

“Where’s the nearest railroad station?”

“About ten miles away. And, frankly, I’m not going to drive you. Nor am I going to lend you one of my horses, although I suppose you could borrow a bike from one of Grania’s children. Or perhaps Monica could whizz you home in her trap.”

Helen burst into tears. Running to the door, she went slap into Grania Pringle.

“Oh, there you are, darling. I’ve been looking for you everywhere, Rupert. Can I borrow you for a sec?”

Helen gave a sob and fled down the passage. She locked herself in the john. Twice someone came and rattled the door, then went away again. The party was still roaring away downstairs and, from the shouts and catcalls, seemed to be spilling out into the garden. Feeling suicidal, she washed her face and combed her hair.

Creeping out into the passage she saw the huge red nightgowned back of Monica Carlton. She was talking to Mrs. Greenslade. Terrified, Helen shot into reverse, taking the nearest door on her left.

12

Helen pushed open the door and found herself in a library where the only gaps in the walls not covered with books were filled with vast family portraits. In one corner on a revolving stand stood a globe of the world with the map of America turned towards her, the states all blurred together and sepia with age. A fire leaping in the grate gave off a sweet, tart smell of apple logs, reminding her of her grandmother’s house in the mountains, and filling her with such homesickness that she had to choke back her sobs and blow her nose several times on an overworked paper handkerchief.

Drawn instinctively towards the bookshelves, she was halfway across the room before she realized a man was sitting in an armchair in front of the fire, reading.

“I am sorry,” she said with a gulp. “I didn’t mean to disturb you.”

“You’re not. I’m hiding.”

“From Mrs. Greenslade?”

“Et alia. We weren’t introduced this afternoon. Malise Gordon.”

He put out his hand.

“Helen Macaulay,” she mumbled.

“Sit down. I’ll get you a glass of Algie’s brandy.”

“Please don’t bother.”

He didn’t answer and went over to the drinks trolley. He was wearing a pinstripe suit, threadbare but well cut across the shoulders, with turn-ups and a fob watch. She noticed the upright, military bearing, the thin mouth, the eyes, courtesy of British Steel Corporation. He was the kind of Englishman one used to see in old war movies, Trevor Howard or Michael Redgrave, who hid any emotion behind a clipped voice, a stiff upper lip, and sangfroid.

“What were you reading?” she asked.

“Rupert Brooke.”

“Oh,” said Helen in surprise, “how lovely. There’s one Rupert Brooke poem I really love. How does it go?

“ ‘These laid the world away’, ”

she began in her soft voice,

“ ‘poured out the red

Sweet wine of youth; gave up the years to be

Of work and joy, and that unhoped serene,

That men call age; and those who would have been

Their sons, they gave, their immortality.’ ”

Her voice broke as she was suddenly stabbed with grief at the thought of Harold Mountjoy’s child that she had lost.

“It’s so beautiful, and so sad,” she went on.

For a second the color seemed to drain out of Malise Gordon’s face. Then he handed Helen the glass of brandy.

“How extraordinary,” he said. “I was just reading that poem. My father was at school with Rupert Brooke.”

“What was he like?”

“Oh, awfully nice, according to my mother.”

“Your father must have some marvelous stories about him.”

“Probably did. Unfortunately he was killed in 1918 in the last advance of the war.”

“That’s just terrible. You never knew your father. Did you go to Rugby too?”

He nodded.

“I so enjoy the Rugby poets,” said Helen. “Walter Savage Landor, Clough, Arnold, they have a deep melancholy about them which I find very appealing. I did the Victorian poets for my major. I think Matthew Arnold is by far the most interesting.”

Seeing her curled up on the sofa, having kicked off her shoes, the firelight flickering on her pale face, Malise thought she was the most beautiful girl he had ever seen. Her ankles were so slender, he wondered how they could bear the weight of her body, or her long slender neck the weight of that glorious Titian hair. Quivering with misery, she was like a beech leaf suddenly blown by the gale against a wall; he had the feeling that, at any moment, the gale might whisk her away again. He would like to have painted her, just like that, against the faded gold sofa.

“Where is Rupert?” he asked.

“Being enjoyed by his adoring public. Actually, he’s just been ‘borrowed’ by Lady Pringle.”

“She’s never been very scrupulous about giving people back.”

“She’s kinda glamorous, but very old,” said Helen. Then, realizing that Grania must be younger than Malise Gordon, added hastily, “for a woman, I mean — or rather a Lady.”

“Hardly,” said Malise, echoing Rupert.

“Oh, I know about the laxatives,” said Helen, “but all these ancestors?” She waved a hand round the walls.

“All fakes,” said Malise, cutting the end off a cigar. “I restore pictures as a sideline. Grania’s great-grandmother over there,” he pointed to a bosomy Victorian lady, “was actually painted in 1963.”

Helen giggled, feeling more cheerful.

“You and Rupert just had a row?”

Helen nodded.

“What about?”

“He wants to go to the max.”

Malise raised his eyebrows.

“In England I think you call it the whole hog.”

“Ah, yes.”

“He’s so arrogant. He ignores me all evening, selling some horse, then expects me to go meekly back and spend the night in his caravan. I said I was going back to London, so he told me to find my own way. I just don’t know what to do.”

“I’ll take you. I’m going back to London tonight.”

“But I live in Shepherd’s Bush; it’s way out. Rupert claims he’s never heard of it.”

“Rupert on occasions can be very affected. It’s about a mile from my flat. It couldn’t be easier to drop you off.”

Cutting through her stammerings of gratitude, he started to ask her about herself, about America, her family, her university, her ambitions to be a writer, and her job. He even knew her boss.

“Nice chap. Never read a book in his life.”

“But no one seems interested in books over here,” sighed Helen, picking up the Rupert Brooke. “This is a first edition and they haven’t even bothered to cut the pages. I don’t understand the British, I mean they have all this marvelous culture on their doorsteps and they’re quite indifferent to it. Half the office hasn’t even been inside St. Paul’s, and John Donne actually preached there. Rupert’s mother has shelves full of first editions. No one ever reads them. She keeps them behind bars, as though they were dangerous animals full of subversive ideas. They never even know who’s painted their ancestors.”

“Unless it’s a Gainsborough they’re going to flog at Christies for half a million,” said Malise. “Then they’re fairly sharp.”

“That lot out there can’t talk about anything but horses,” said Helen bitterly.

“You mustn’t blame them,” said Malise. “For most of the season, which goes on sadly for most of the year now, they’re spending twenty-four hours a day with those horses, studying them, schooling, worrying about their health, chauffeuring them from one show to another. That lot you met next door have battled their way to the top against the fiercest competition. And it hasn’t been easy. We’re in the middle of a recession; petrol prices are rocketing; overheads are colossal. Show jumping’s a very tough competitive sport and only a few make it, and unless they keep on winning, they don’t survive.”

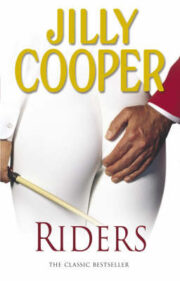

"Riders" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Riders". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Riders" друзьям в соцсетях.